The nature of documentary cinema has been up for debate ever since the term ‘documentary’ was itself first coined by John Grierson in a review of Robert Flaherty’s Moana in 1926. In the intervening years, definitions have varied – some prioritising artistic merit, and others journalistic integrity, with clarity on the issue ultimately proving impossible to come by. Even in Flaherty’s early film, the reality presented is not quite as it seems; the Inuit and Samoans in Moana were in fact re-enacting earlier events from memory for the benefit of the filmmaker.

Frames of Representation ran 20-27 April 2016 at the ICA London.

Behemoth and Brothers both next screen at Sheffield Doc/Fest, running 10-15 June.

Frames of Representation will next preview Gianfranco Rosi’s Fire at Sea on 9 June (see our review) and Bill and Turner Ross’s Western on 26 June.

In the introduction of their book Faking It: Mock-Documentary and the Subversion of Factuality, Jane Roscoe and Craig Hight argue that “…documentary texts operate along a continuum between fact and fiction, with the majority of documentaries being grouped at one end, but with a considerable number of others that have tested the basic tenets of factual discourse.” It is these films, these ‘others’ traversing the blurred boundary between fact and fiction – art and journalism – that are the focus of the new film festival, Frames of Representation.

With its inaugural programme recently playing at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London at the end of April, Frames of Representation aims to explore the continuing evolution of the documentary form. Moreover, festival curators Nico Marzano and Luke W Moody used the film screenings as a launchpad to stimulate discourse about the potential of the medium and the implications – ethical, emotional, aesthetic – of working on the fringes of the documentary film. Their desire has been not just to engage filmmakers with these issues, but to serve as a thought-provoking catalyst for audience interaction, too.

This sentiment chimes with a more widely observed trend focused on broadening the scope of documentary festivals and kick-starting conversations about perspective, creativity and responsibility in a world flooded with nonfiction imagery. It is not enough for those creating the images to grapple with how they are presenting them, but audiences must consider how and why they are seeing them, too. With the audience’s complicit role in mind, it’s no coincidence that filmmaker and writer Treasa O’Brien, while chairing a panel discussion on the festival’s final day, made mention of Susan Sontag and her seminal essay Regarding the Pain of Others.

Behemoth, Zhao Liang’s statuesque portrait of land extraction and human exploitation

If extremely healthy attendance figures are anything to go by, it seems as though the festival objectives were met. The ICA was transformed into a hive of discussion and audiences relished the opportunity to talk shop with an array of interesting filmmakers. “It seems there is genuine audience demand for new forms of documentary cinema and we believe Frames can help fill this gap,” said co-curator Marzano. “Hopefully we created a space to share dialogue and rethink the boundaries of art, documentary and fiction.”

That dialogue was made even more imperative by the theme chosen for the festival’s first year: The New Periphery. All of the films included in the small but perfectly formed programme exist on the periphery of the documentary industry themselves and gave voice, in a wide variety of ways, to people on the margins of society whose stories are seldom told. This led to timely and much-needed conversations in which questions about romanticisation and cultural appropriation were genuinely encouraged.

Themes such as these gave the atmosphere a sharp edge in the Q&A session that followed the screening of Fragment 53. An arresting piece of work, Fragment 53 explores notions of warrior-hood through the lens of the Liberian civil wars via interviews with a number of former generals from various factions of the conflict. It is, in many ways, an austere and somewhat more ambiguous cousin to Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing.

‘Evocation over education’: Federico Lodoli and Carlo Gabriele Tribbioli’s Fragment 53

Unlike Oppenheimer’s film, however, Fragment 53’s directors Federico Lodoli and Carlo Gabriele Tribbioli made the conscious decision not to contextualise the candid and gripping accounts they captured. They opted for evocation over education, and audiences are challenged to make their own connections between the interviewees (it is telling that one of the most commonly repeated words, by spiritualist and soldier alike, was ‘brave’) and contemplate the universality of these war-time perspectives. It’s a decision that inspired a fascinating and wide-ranging discussion between the two directors, the moderator – writer and academic Jean-Paul Martinon – and the audience. The debate that followed took in the filmmakers’ ethical accountability to the victims of war, their duty to inform audiences and the thorny subject of European voices framing a Liberian story.

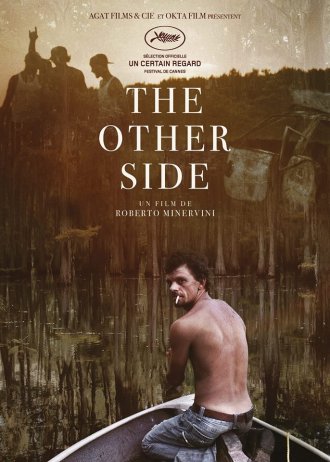

The notion of moral responsibility continued and is something that filmmaker Roberto Minervini speaks about with a great deal of eloquence and self-awareness. His latest film, The Other Side, was chosen as the opening night screening of the festival and it’s clear to see why: he and his picture embody what Frames of Representation is really all about. Indeed, The Other Side was actually one of the initial inspirations for the festival.

Cathartic ‘restored behaviour’ in Roberto Minervini’s The Other Side

“I am very aware of the fact that I’m working in the limbo between documentary and fiction,” Minervini explained. “For me, that is important because I believe that conventional documentaries are subject to a pre-conceived dogmas that stem from journalism that, in filmmaking, can become dangerous because they can make the filmmaker a little less responsible.” For Minervini, the merry dance along the boundary between fact and fiction gives him a stronger sense of his authorial voice and forces to him to assume and test his responsibility.

He also feels that the construction of his films (honed throughout his much-admired Texas trilogy), and his active engagement with the concept of ‘restored behaviour’ through re-enactment, gives his work meaning. In The Other Side, Minervini creates a secure environment and builds up enough trust to encourage his disenfranchised subjects, Mark and Lisa (both drug addicts with commuted prison sentences), to allow him to witness incredibly intimate moments – in both real-time or in a re-run. Filmed over several months in Louisiana and at Mark and Lisa’s own pace, the method was one of utter collaboration.

The film ends, as did Minervini’s previous work, Stop the Pounding Heart, when the protagonist tells him that they’ve had enough of bearing their soul to his camera. Minervini recalls moments of catharsis, both for himself and for his actors/collaborators, while his deep empathy for Mark, Lisa and everyone featured, is evident on and off the screen.

One of the great joys of festival viewing is the unexpected repetition of motifs, themes or even visual cues across otherwise unconnected films. There are many threads of The Other Side that can be found within the make-up of rest of the festival line-up, but a striking one comes in the form of the image of Mark sat at the prow of a rowing boat – an image which has been used a lot to advertise the film (above). It draws attention to two other films shown at Frames of Representation that feature men gliding over water in single-person vessels.

A town on the Southern Gothic edge: Ewan McNicol and Anna Sandilands’ Uncertain

Just across the state border in Texas, for example, live the subjects of Ewan McNicol and Anna Sandilands’ absorbing portrait of a town on the edge of collapse in Uncertain. Like The Other Side, it is beautifully lensed, steeping the town of Uncertain in a Southern-Gothic atmosphere. Uncertain explores the commonalities between the precarious futures of a trio of inhabitants, alongside that of the town’s own embattled eco-system as it is attacked by a voracious botanic parasite.

Uncertain’s population of just 94 souls looks positively thriving in comparison to San Marco, the submerged Mexican town featured in Betzabé García’s beautiful and desolate Kings of Nowhere. It opens with a young man on a vessel once again – this time a motorboat – sliding past buildings peeking out of the water.

After the flood: Betzabé García’s magic-realist folk fable Kings of Nowhere

García eschews any context until the closing titles, instead allowing the audience to be slowly beguiled by the folkloric sight of a handful of people still navigating their ruined, waterlogged home. “We wanted to highlight the atmosphere, bordering on magical realism,” says the director in an interview in the festival brochure. It is also perhaps the reason that an external menace (a militia? Bandits? Local government?) are referenced in passing by several people but never glimpsed or fully explained. They remain as ephemeral as a gruesome bedtime story to scare children to bed.

Kings of Nowhere has much in common with the other Mexican film in the programme, Pablo Chavarría Gutiérrez’s The Letters, but the latter pushes even further away from traditional modes of documentary storytelling. Probably the least conventional film on show, it is an experiment in what film scholar Erik Knudsen has described as ‘transcendental reality’. Not just devoid of context, but also largely free of dialogue, The Letters is a subtle sensory exploration of the psychology of a man and a community – though neither of those assertions is readily apparent.

‘Transcendental reality’: Pablo Chavarría Gutiérrez’s elusive, foreboding The Letters

Instead, Gutiérrez rebels against the co-opting of nonfiction imagery by Mexico’s biased mainstream media, and bristles at the very idea of reality as something that can be captured by a filmmaker. He tells the most esoteric of stories through snatches of memory, in a way that always feels as though explanation is waiting just outside the frame, or exposition was coming just after the cut. The Letters evokes a sense of foreboding, of injustice, of brutality, tradition, and enchantment through kinetic camerawork and artful, stylised composition. Part-art installation, part-modern dance, part-state of the nation, it is a truly singular work whose very nature demands exactly the sort of scrutiny, and engagement with documentary form and ethics, that is the festival’s raison d’être.

Novelist and filmmaker Xiaolu Guo provided valuable summation she told a sold-out masterclass on new Chinese documentary that she is “very suspicious about the idea that documentary is the truth.” Vietnamese filmmaker Trinh T. Minh-ha once went further and proclaimed that “there is no such thing as documentary,” but Guo’s reservation is perhaps more helpful for engendered debate. It’s a succinct expression of welcome uncertainty about the objectivity of the medium and its often unquestioned claim to reality.

This is a vitally important tenet of the documentary experience that may be inevitable in an eclectic programme of avant-garde offerings accompanied by intelligent and thought-provoking panels. However, it also needs to become commonplace when watching documentaries that are less engaged with, or open about, their own modes of representation and possibly less overtly demand self-reflection from the audience. Andrea Luka Zimmerman, director of Estate, a Reverie, was part of the closing panel discussion and discussed how even the word ‘marginalised’ troubles her as it “ascribes a narrative by which we perceive people.”

‘The unspoken warmth of a lifelong bond’ in Wojciech Staroń’s Brothers

Fetishisation was another potential pitfall raised in the same panel, particularly pertinent for films about suffering that are highly aestheticised. Fortunately, by focusing on such docu-fiction-art hybrids, Frames of Representation has been able to showcase a number of very well-received films that may never have otherwise screened in the UK – from the devastation of the Mongolian plains in Zhao Liang’s powerful and moving Behemoth, to the unspoken warmth of a lifelong bond in Wojciech Staroń’s Brothers and the sad lament of an orphaned buffalo calf in Pietro Marcello’s quirky and lyrical Lost and Beautiful. More importantly, though, the festival has continued the fine work being done at other similar events like True/False in Columbia, Missouri and CPH:DOX in Copenhagen by inspiring audiences to truly interrogate crucial issues in documentary cinema that are all too often left on the periphery.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.