“Obviously a film is in 2D, but watching it silent, without any sound, seems like watching something 3D crushed into 2D. Music brings it to life, fills in that third dimension and helps you connect with the film.”

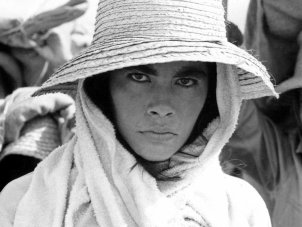

Anoushka Shankar

Credit: Laura Lewis/DG

Shiraz: A Romance of India with Anoushka Shankar’s new score premiered as the Archive Gala of the 2017 BFI London Film Festival at the Barbican Cinema, and is now available to buy on dual-format Blu-ray and DVD.

It is streaming in the with a new introduction from BFI Head Curator Robin Baker on YouTube on 2 June 2020.

Anoushka Shankar is talking about Shiraz (1928), one of the few surviving Indian silent films – a ‘Romance of India’, telling the love story of the princess who inspired the building of the Taj Mahal – which has been newly restored by the BFI National Archive, and for which Shankar has been commissioned to write a new score. Ninety years after its making, by the German director Franz Osten and Indian actor-producer Himanshu Rai, this Indian/British/German co-production forms the centrepiece of the BFI’s India on Film programme marking the 70th anniversary of Indian Independence, and the world premiere of Shankar’s score provides the Archive Gala for the 2017 London Film Festival.

Writing her first film score, Shankar was well aware of the range of choices she had to make for her musical cues. “I could try and be faithful to the period it’s set in – the 17th century; the period it was made – the 1920s; or the period I’m writing in – today,” she explains. “And in the end, it’s a mixture of all those things. I try and keep a balance between moments in the film where it feels appropriate to stay quite authentic and allow the Indian instruments to play in a traditional way. But elsewhere I want it to be more a film experience and to make the music more immersive so people become more involved in the film. This means a rich, broad sound palette with lower, deeper tones that don’t really exist in the Indian soundscape.”

Shankar’s orchestra is a mixture of Indian and Western instruments: her own, sitar, bansuri (bamboo flute) and percussion for the Indian colour, plus violin, cello, clarinet and keyboards for the more expansive filmic moments.

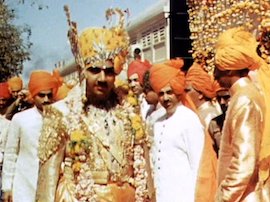

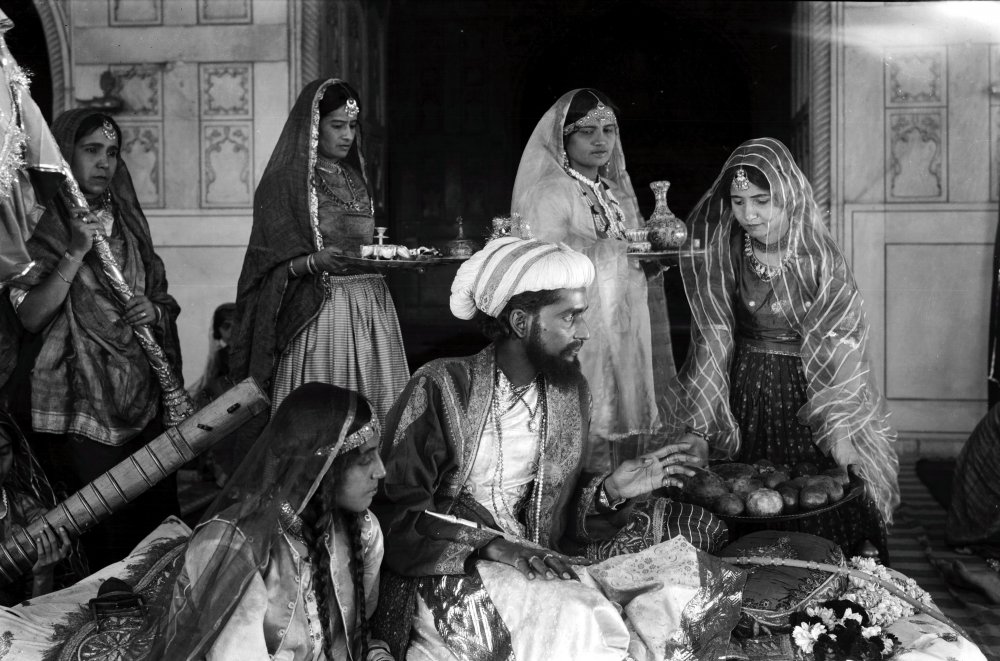

Rao with Himansu Rai as Shiraz

Shankar’s famous musician father Ravi also wrote film music, notably for Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy in the mid-50s. He said he was so inspired by seeing Pather Panchali, the first film in the trilogy, that he composed the music in just four and a half hours. A tough act to follow, but Shankar is used to working in his shadow, both as sitarist and composer.

“I was attracted to the idea there was no director,” she admits. “I know how to write music, but I’ve never had any experience in realising someone else’s vision with my music. In that sense it seemed a great opportunity to have carte blanche. But having done it, I think a director would have been extremely helpful to help me find and pull out the key narrative at a given moment. So I’ve made a lot of decisions on my own which I hope are the right ones.”

Osten and Rai made a trilogy of silent movies together, all shot on location in India. The first, Prem Sanyas (Light of Asia, 1925), was about the early life of Buddha with Rai playing the central role. Shiraz (1928) was the second and the third was Prapancha Pash (A Throw of Dice, 1929), in which Rai played the devious Rajasthani King Sohat. The BFI commissioned a dynamic Throw of Dice score from Nitin Sawhney ten years ago.

Shiraz is a historical romance about the creation of India’s most famous landmark, a monument to love built by Shah Jahan. In the fictional story, Rai plays Shiraz, the childhood friend and love of Selima. She is kidnapped, sold to the Crown Prince, the future Shah Jahan, and eventually becomes his wife. For fraternising with Selima, Shiraz is sentenced to be trodden to death by an elephant. But reprieved at the last moment, he ends up creating the superlative architectural model of the Taj Mahal – a monument to both the Emperor’s and his own undying love for Selima. Two loves, not one, immortalised in marble.

There’s little history in there, but it’s an affecting drama, given an extra veracity by the locations. We see camel trains and marauding horsemen riding across the desert. There’s the crowded slave market, elephants and the luxury of the palace inside and out. It’s understandable why it had such an impact.

“Overall it’s quite a visionary film,” says Shankar. “It’s a great story, really well made and beautifully shot.” But it’s a story of supreme male power, which perhaps has uncomfortable overtones in the 21st century. “Selima is brought as a slave to the palace and he takes a fancy to her,” explains Anoushka. “There’s a quasi-romantic walk in the garden and he leans in to kiss her and she resists. He says ‘You know I have the power to take what I will?’ and she smiles at him and says, ‘But you don’t have the power to take my love’, which neatly redresses the balance.”

Charu Roy as Prince Khurram

Much Indian music is improvised, of course, but Shankar feels that for the film, the pictures and music need to be very closely matched. “I think what the music brings is the emotional depth and it needs to be orchestrated for the instruments I’m using. I write out a scratch notation, and we play to a click track – we have to. It’s something I generally don’t like doing, but once there’s film involved, being just a few beats-per-minute off could have unpleasant consequences.

“When I started I joked about film scores having lots of repetition,” Shankar admits. “But it’s been interesting learning how music in the context of film works. As soon as the music gets too busy it becomes a distraction. So that’s where the repetition comes in useful, so they don’t have to work so hard as listeners. Above all you’re wanting people to watch the film.”

In the October 2015 issue of Sight & Sound

Primal screen: Cross-border appeal

A new restoration of a silent epic opens a window on Indian filmmaking – and shows that 1928 was a good year for a Shiraz. By Bryony Dixon.

-

BFI London Film Festival 2017 – all our coverage

Follow all our coverage of the 61st London Film Festival, including reviews of the top films, interviews with their makers and blog posts from our...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.