This is an extended version of an interview printed in our October 2013 issue

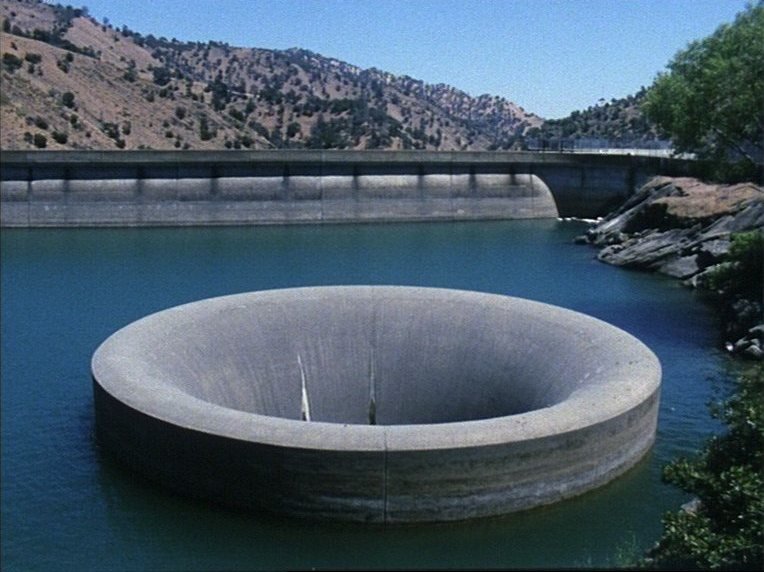

casting a glance (2007)

Look. Listen. Pay attention. Be alert, attuned, patient. Heed your own senses; hone them, heighten them. Focus, engage the moment, be here now – and notice how anyway thoughts, memories, expectations, presumptions and self-distractions come teeming in. James Benning’s movies pose an idealistic challenge, a spur to unattainably pure observation, but this recognition of the subjectivity of experience is also part of their plan.

To newcomers, Benning’s cinema can come as a shock, even intimidate. The spartan rigour of its design makes most narrative movies look like victims of attention deficit disorder (and their audiences victims of informational spoon-feeding). Harking back to the actualities of early, pre-story cinema, it extends their direct gaze – exploring the properties of both the world and our perceptual apparatus, typically with a static camera – into increasingly extreme duration.

James Benning

Uncharted States of America: a James Benning tribute runs 1-6 April 2014 at the Bradford Film Festival and includes the world premiere of Benning’s BNSF on 5 April.

DVD editions of American Dreams + Landscape Suicide, RR + casting a glance, the California Trilogy and Deseret + Four Corners are available from the Austria Film Museum.

One Way Boogie Woogie (1978), an early marker of Benning’s maverick formalism, deployed shots uniformly 60 seconds long (while carving up the frame in a flat tribute to Mondrian). The three parts of his California Trilogy – El Valley Centro (2000), Los (2001) and Sogobi (2002) – each presented 35 shots two-and-a-half minutes long, the running time of a 100-foot roll of 16mm film; 13 Lakes (2005) and Ten Skies (2005) captured their titular subjects in ten-minute takes, or the larger 400-feet rolls.

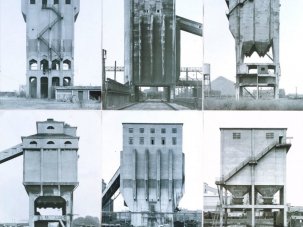

When in 2008 this valiant keeper of the celluloid faith finally relinquished his beloved 16mm for digital video – in despair at the prospects for film projection more than production – the new technology emboldened him further. Ruhr (2009), his one venture wholly outside the United States, to the industrial heartlands of Duisburg (he comes from German emigrant stock), ended with an hour-long study of a smokestack at sunset, while experiments like John Krieg Exiting the Falk Corporation in 1971 (2010) and Faces (2011) each used digital editing programs to slow down short found-footage fragments (from Benning’s own early work Time and a Half (1972) and John Cassavetes’ 1968 film of the same name, respectively) to feature length. (Other Benning films have allowed their subjects to dictate the length of a shot: readings from New York Times articles in Deseret (1995), trains passing through the frame in RR (2008), cars in small roads (2011), the length of a smoke in 20 Cigarettes (2011).)

Benning grew up in a blue-collar Milwaukee, Wisconsin community which tore itself apart in the race battles of the 1960s; he recalls being beaten up by former neighbours when he became a civil rights organiser. He studied maths on a baseball scholarship at the local university, and won note as a rare Midwesterner in the 70s American experimental film scene with his early contributions to the structuralist movement in the 1970s.

Grand Opera (1979)

In this most collaborative, often corporate medium he may stand out as a rugged individualist, clocking up hundreds of thousands of solo car miles to find and report back on the sights and sounds of his country, and making frequent reference to the lineage of American outsider art that starts with Henry David Thoreau, whose cabin at Walden Pond Benning has reconstructed in the forests of the Sierra Nevada (along with another by Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber).

Yet as his movies contemplate landscape as a function of time, so they reveal history, from the specifics of his own autobiography and forays-with-camera to the whole bitter chronicle of American colonial and industrial conquest, class struggle, violence and ecological ravages. “All my films,” he has said, “are an attempt to ask, how liberated am I? Where did I come from? How am I progressing?”

In 1987 Benning left the New York art scene to teach film at the California Institute of the Arts, outside Los Angeles; he has lived since then in Val Verde, an outpost of that outpost. Along with his ‘Math as art’ class, his most famous teaching innovation has been his ‘Listening and Seeing’ class, essentially an extension of his own working process, in which students are taken out into a variety of landscapes, be it desert, an oil refinery, a ghost town or Skid Row, and asked to pay attention. His movies, meanwhile, have influenced numerous others – most clearly his peers and mentees in America, but one can find echoes as far afield as Chantal Akerman, Patrick Keiller, Abbas Kiarostami, even Michael Haneke…

As well as revisiting and remixing old work – like John Smith, another filmmaker who has made structuralism his own – Benning has belatedly made his peace with digital exhibition, releasing an ongoing series of his old films on DVD as part of a donation of his archive to the Austrian Film Museum. I spoke to him in Vienna during one of his regular visits to the museum to show new work.

Landscape Suicide (1986)

What finally pushed you to putting your films on DVD?

I realised I had 30 years’ worth of work that needed proper storage and archiving. And to be fair to the work it should be properly done: I just didn’t have the time or money to properly archive it. If I tried it would have pretty much consumed the rest of my life, and I’d stop making work and be a slave to what I had already done.

The Film Museum had always been a great supporter of my work. It’s a perfect place for me because I’ve never been categorised properly – I don’t know if I fit into categorising. I found an institution that loves film and doesn’t have a narrow vision of it; they care about what they think are good films. And luckily they think my films are good.

When Alex [Horwath, the museum’s director] offered to store it I said he could just have it all, with the idea that they would properly archive it over the years, because I knew it was a huge job. As part of that archiving process, they thought they should also make DVDs to make the films available. And at that point I thought it was a great idea, mainly because there seemed to be a demand to see those early films, and I couldn’t provide a solution by renting prints any more. The internet’s made my work talked about more; it’s actually found its place in the world, where before it was in little corners. I’ve been holding out for years not to make DVDs, but now the writing’s on the wall. And you get a sense of the films, anyways.

Are there any films you wouldn’t feel comfortable releasing?

I don’t want to make that choice. They were made by me and whether or not they’re important I think they should be done, because it’s part of an archive and shouldn’t be edited. In the end maybe ones that don’t play well now or I didn’t like might be more interesting than the other ones. There are a few I’m not real happy with, but that’s mainly not because they’re good or bad films but for other, personal reasons; they talk about something I don’t want to talk about anymore.

RR (2008)

When I watched a retrospective of your films at CalArts in 2007 you were finishing your final 16mm films, and your career seemed very linear, from finding your themes and identity in your early experiments to the rigorous distillations of your landscape films, in which you stripped away text, voiceover, people… Now it seems obviously spherical, with all these different experiments and echoes and reworkings of earlier films.

True, and that’s because of the switch to digital. I thought, okay, I’m in a new medium, and I can think back to when I first started making films and didn’t know what direction I was going in. I experimented, not in the sense of ‘experimental films’ but real experimentation: what can a camera do with this lens? What can it do with that?

I’ve gone through pretty much that same process now with digital filmmaking and became more playful – because I wasn’t aware of what this digital technology could actually do, and wanted [to find out]. So in a way there’s a circular trajectory, because I’m re-learning a whole set of variables like I did when I first started. And that’s exciting. And by doing that I started to think about what those works were, what I liked in them and how I could pluck out things I liked and expand them by digitally copying them and slowing them down, re-editing them… things I’d never have thought of doing with film because it would have involved optical printing and taken years, but which I can now do in an afternoon.

And it costs me nothing once I’ve bought the equipment because I do everything myself; if I don’t like it I can just erase it and say ‘Okay, I experimented for a week and it didn’t work’, or ‘Great, I have a new film and it didn’t cost me a penny.’ And it’s rethinking what I did, looking at ideas from 20-30 years ago in a whole fresh way.

So yeah, I’m excited. And you’re absolutely right that it’s a circle of reworking and reflecting. Perhaps that’s what happens when you get to be my age. You look back at things and try to make sense out if them. So in a way the archiving of the films put them here and then they represent them as DVDs, which means a whole new generation of people can see my work now. Not in the proper way, but they’re used to looking at DVDs and I think it’s maybe an interesting time to loosen up and not be so pure.

casting a glance (2007)

Might you have been this prolific sooner if you’d moved to digital earlier?

I don’t think I would have. The earlier digital equipment didn’t render images quite as good as they do now. The only video images that I actually liked before the current camera I have [a Sony EX3] goes way back to the late 80s when they made these little video cameras called… Hi8, were they? They were very painterly and absolutely gorgeous. At that moment I thought I might buy one of those and start to play with it. That was around the time I found a Pixel[vision] camera and played with that for a few months before deciding against it. I made a few [videos], but none of them exist any more because they were all on those little quarter-inch audio tapes that just degraded. Then my daughter [Sadie] got one and proved me wrong, that they really were amazing cameras.

Do you think future moviemakers who’ll never have touched a film strip will have lost something? Should they experience analogue filmmaking?

I would tend to advise them not. Let’s see where you can go without having that prior [experience]. I’m making digital works now with the whole set of ideas I’m bringing from the past – still thinking in terms of optical printing and mimicking things from the old film world – which I suppose is valuable, if you know those things, but maybe that’s holding me back from really breaking into what this new stuff can do, collaging and all these other programs. Maybe you should start to work with totally new ideas that aren’t connected to film at all.

I don’t know if that’s good advice or not. That’s a complex thing, how the human brain works, what bogs you down. Maybe if you don’t know the past you won’t develop those prejudices in the future? Maybe our track record as human beings is so bad that we shouldn’t remember the past? People say ‘Never forget’; maybe it’s good to forget, sometimes.

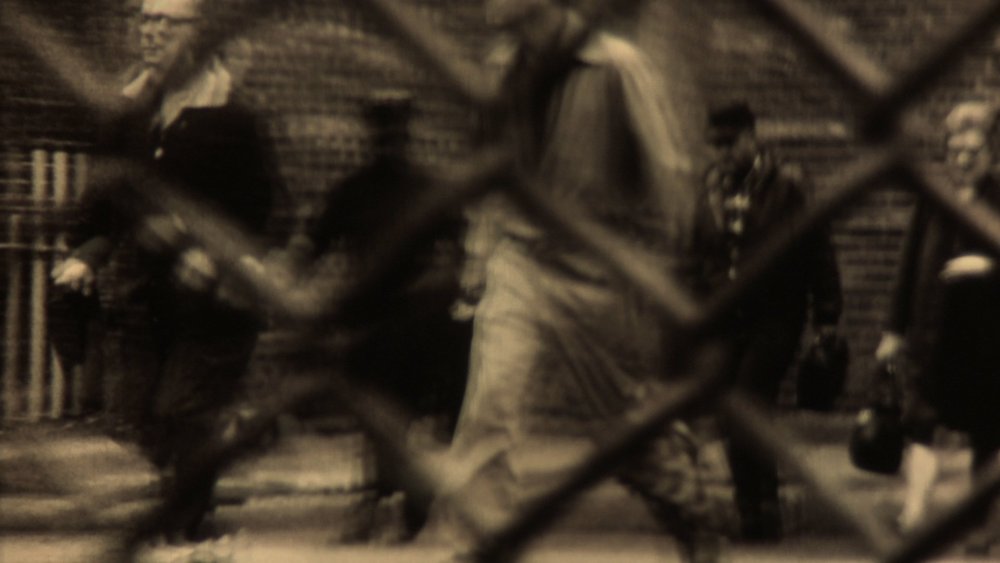

John Krieg Exiting the Falk Corporation in 1971 (2010)

It’s interesting about the collaging: one of your new movies, small roads, ostensibly looks less of a rupture with your landscape films than, say, Ruhr or Twenty Cigarettes…

I was trying to make a film that went back to my prior filmmaking and again this circle back to ideas of our landscape cut by the railroad track now being cut by the road… All those things that directly refer back to RR.

And I also used all this new digital technology to make the image look more like the images that I used to make in film. Rather than like when I made John Krieg, where I stretched 14 seconds of worker leaving the factory to 71 minutes, with this digital frame-blending that gives it multiple exposures and makes it like Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, with its multiple views of movement. And depending on the pan and zoom of the camera, [the movie] keeps breaking apart and coming back together – a normal image that splits into many facets and then comes back.

That digital technology is out of this world; I’ve never seen anything like it before. It’s a button on the camera, changing 100 to 0.3 per cent in Final Cut Pro’s speed setting and all of a sudden you’ve got this incredibly Duchampian painting in front of your face: you can’t see that way and it’s beautiful.

And yet in small roads I’m doing much more manipulation – it took me months to do – and you’re not aware of it. It looks more real than any of the films that I’ve made. I’m trying to make real sense of landscape by using real collages that are really highly manipulated but undetected. So that’s an interesting way that the frame can be torn and multiplied by technical means, and completely collaged together in a way that looks absolutely real too. The equipment can take you in either direction – to the total abstracting of the image or towards a much closer reality.

small roads (2011)

For instance, if I’m filming in an area where generally there’s thunderstorms that come through every afternoon, but the day I happen to be there it’s sunny, that’s more false than collaging it to look like what it generally is, right? When I shot those cattle on the side of the road I was hoping for afternoon rainstorm… and it just didn’t happen.

The next day I was a hundred miles or so away and there’s the rainstorm. Different landscape completely, but I simply tilted the camera up to eliminate the hills and shot the sky; then I’d just bring that in, crop it and you can fuzz the edge of the image so it just falls in and you don’t even notice it’s a different place. So in a way it’s manipulation, but in small roads everything I manipulated made it more real to me: I’m trying to reinforce reality. And in John Krieg it’s the opposite: everything I did makes you see like you’re on some psychedelic drug and in some weird time-warp.

Which raises the question: how important is indexical documentary to you, in terms of the image imprinting what you find in the world?

See, I don’t believe that’s possible. Because the biggest manipulation is the frame, and what you leave out and how you take everything else out of context by taking just the small portion of the world. And therefore it’s silly to talk about ‘complete reality’. It’s always your point of view what you leave out and where you point the camera… A lot of people want my films to be that, but they’ve never been that. They’ve always been a selection, always been colour-corrected, always been highly manipulated with sound. They’ve always taken a real point of view from what I believe in, and I am full of prejudice. And those prejudices are on the screen.

But then when you make it more real and try to eliminate your prejudice by collaging then people say “Oh, that’s worse.” My argument is it’s better; it’s closer to reality. I don’t see it as cheating. I saw it as playful and having fun, because it was really fun to be able to do that and have that control. And of course, Hollywood images have been doing that for all these corporations, ‘Magic Light Lantern’ or whatever the names of them are [laughs]…

Ruhr (2009)

Dreamworks!

You know them. I mean, they’ve been doing this brilliant manipulation, but in more fantasy work or science fiction or whatever. But I suppose it happens in normal narrative films too.

Do you have any interest in mainstream cinema these days?

I don’t at all. CalArts has a film class where they show a film every Friday from rather new directors or new films from all over the world, and that’s my education, basically. I have no desire to go to any store-bought films in the mall. I don’t know why people would even spend money on those things… Then every once in awhile I miss something and somebody tells me about a film that was actually quite good in that context, but I never saw. I’m thinking of… what is the Gus van Sant where they’re walking in the desert?

Gerry [2001].

I never saw that and I wish I had, so maybe I’ll find a DVD [laughs]. That probably will come back at some point and I should see that in a theatre.

Deseret (1995)

You don’t have any sense of kinship or how you’ve influenced other filmmakers?

I’m not sure if I have or not. People showed 13 Lakes with, er… [Abbas Kiarostami’s] Five, is it? And I saw things written about how it might have influenced him, but I think it’s coincidence, because people get ideas from here and there.

I don’t know, my films show around, so it’s possible. I always think I’m this tiny [he gestures], so how do people even know? But now with the internet there’s that possibility of happening – and I do have younger filmmakers always telling me how much my films have influenced them. They’re the ones who still admit to influences…

I was going to bring up Kiarostami. I wouldn’t assume he’d been watching you, and he’s been working for decades, but there are all sorts of fascinating comparison points, especially with his more recent studies like Five, or Ten [2002], where he left the cast alone with the camera, like in 20 Cigarettes – or Shirin [2008], which just watched the faces of a cinema audience.

That I saw. Lately, and probably always, a major influence has been Warhol, just because of his interest in the everyday, and also in duration. Michael Snow and Hollis Frampton have been influences from the very beginning. And contemporaries I connect with are Sharon Lockhart and Peter Hutton. Sharon’s a generation back, but we share a lot of ideas. But I don’t see a lot of films. I should see more.

13 Lakes (2005)

I know you’ve seen Lisandro Alonso’s films, for instance. They seem part of a big movement in arthouse cinema over the past decade or so that works with long shots, asks for patience and is obviously a reaction to contemporary Hollywood movies. What do you think of the term ‘slow cinema’, which some people have applied to films that work with duration?

I always believe that any learning comes through concentration and patience, and that you have to train yourself to have that patience and to perceive. That isn’t slow to me, that’s hard work. It may be slow in the movement of things but it isn’t slow in the stuff that’s going on in your mind when you watch something for a long time and you see very minimal changes: you start to learn from that. So time is a function of becoming more intelligent, I think; you need to take time. The word ‘slow’ seems to belittle that process. How can you rush that?

I remember years ago when I saw a neighbourhood film with Gene Hackman… Night Moves [1975]. He’s talking about an Eric Rohmer movie and says “It’s like watching paint dry”, and when he said that I thought “Oh, that’s what I have to aspire to!” That’s so brilliant, to make a film that would require such concentration that you would notice paint drying. And then to actually feel the way the paint dries, the way light would come off the wall in a different way when it’s [wet and dry]: as that transformation comes I think you could learn a lot about light.

I’m kind of joking, but at the same time I’m serious. That’s not slow, that’s hard work and learning.

One Way Boogie Woogie (1978)

There was a nice quote in the [Austrian Film] Museum’s book, where you talk about a 90-second shot in One Way Boogie Woogie, and your initial reaction was “This is far long, it’s going to kill the audience.” And then you thought “Well, no, maybe they need to learn to watch this”, and now you wish that shot had been ten minutes long… Has it been a slow learning process coming round to that pace, or was there a ‘eureka!’ moment?

No, slowly. Like watching Landscape Suicide and seeing those landscapes: they just go so quickly that you just get a sense of them and they’re gone. And then the sound I made is a bit overproduced, so you’re not really feeling the true landscape yet, but especially because they’re such short shots: 40 seconds! At the time I thought they were long, but now I realise they’re way too short to really learn anything. Now they become just a quick impression, which can be very false, rather than a real feel for a place, which takes time.

Do you think digital technology is making the world increasingly distractable?

I mean… the whole computerised world now is somewhat distressing with cellphones. People constantly have to check things, and then they just check for a second and leave. It’s just all so weird to me; it’s a weird world that we’re in.

But there are people who are realising that too, and are going in the opposite direction… Some people are learning how to work with technology so it doesn’t completely destroy their autonomy. Like, for me, I’ve been thinking very much about the computer and what [Unabomber Ted] Kaczynski’s written about technology, and that is that the computer offers me complete autonomy in my work; I don’t need a lab, I can do these collages, all this stuff by myself. Sometimes I need some help from a few technicians, but basically it’s not like I have to buy things to make a film any more. It’s all available once I have this equipment.

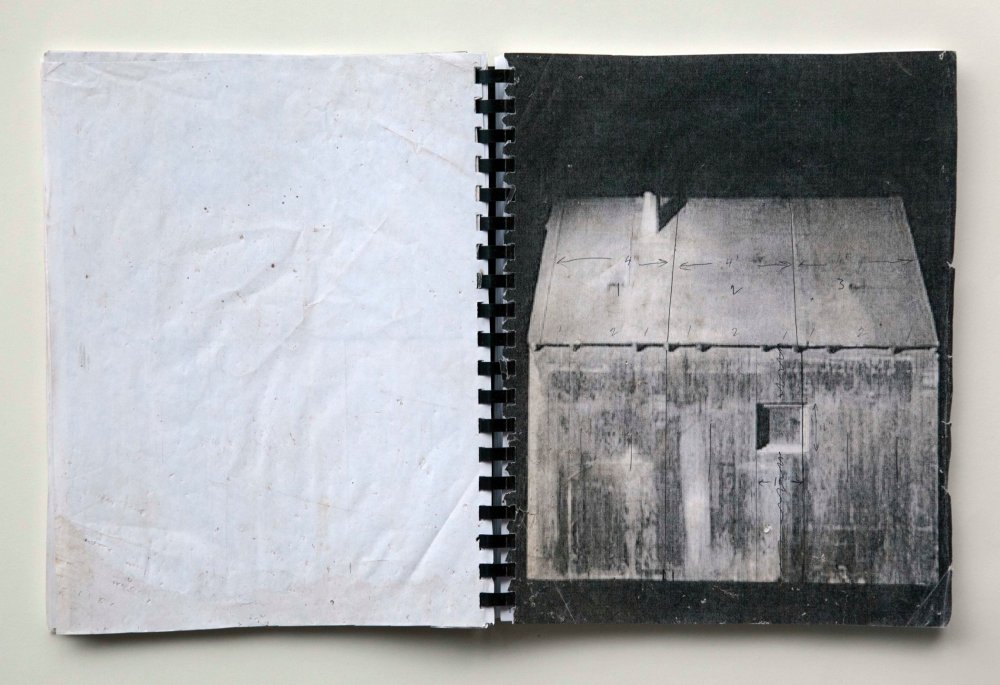

A spread from Two Cabins by JB, co-edited by James Benning and Julie Ault (A.R.T. Press, 2011)

But because of that I can work constantly now, because it doesn’t cost. All of a sudden maybe the more important autonomy of control, of what your life is about, has gone. Now I’m the slave to this machine, working and concentrating on what I want to do. Now I like that, but at the same time I’m not sure it’s healthy. It’s something one has to negotiate.

And when I see young students who can’t let go of their cellphones, constantly having to text and do that, that worries me… it’s so seductive. A lot of it’s just nonsense, right, what’s going on with those things? Or maybe they have important things to text, but I doubt it.

Do you leave your computer behind when you go out to your wood cabin?

No, I almost always take it up there because I edit on it, and get a lot of work done. But that’s where I have it more under control because up there I can work for four hours, get a lot done, it’s quiet. Shut it off and then go out and chop wood because I have to get so much wood ready for the winter. And then I can go for a walk, enjoy the outside and have this connection to being in a real place rather than in front of a computer. One you can smell and taste, walk through and be part of. So it’s a stronger connection to life.

But then I’m happy to go back to work, too, because I like the intellectual connection I have with this machine which helps me solve problems for the art I’m making. Then you have this other weird love relationship with it, because it’s so phenomenal in a way. So I’m a contradiction. But I don’t want just to go to one side or the other.

Stemple Pass (2012)

It sounds a common experience.

Well, that’s good if it’s common, because I’m afraid so many people just go home and play video games all night. Especially violent games, like stealing a car or something.

I had a guy who lived across the street from me in Val Verde, in a very little house, all alone. Every night you could see the glow of his video screen and hear the game, all night all long. I felt bad for him – that’s all he would do. Then he moved out, I don’t know where – maybe to a mental institution.

Then a Mexican family moved in, brought some tents and trailers, and all of a sudden there’s like 15 people living there, parties and music: real life was across the street. They’d make noise, but were very considerate, and still are. The culture is kind of flaunted in their front yards: they became like a diorama for studying what this kind of extended family was about.

And I live all alone there, so I’m probably a lonely guy like the video guy, but I don’t do that. I do other things. But I’m happy they’re my new neighbours. Very enlightening.

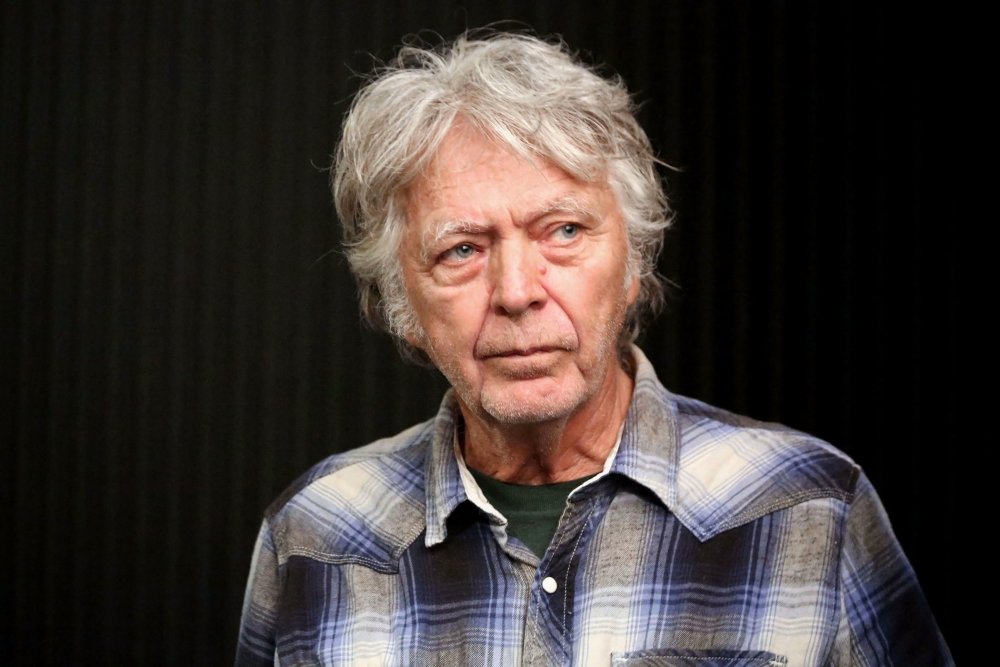

Sharon Lockhart in Benning’s 20 Cigarettes (2011)

You’ve had people in your films before, but Twenty Cigarettes is obviously noteworthy in focusing on faces for its duration. Can you imagine now making a film with even more people, or more than one person in the frame? Or is that just not you?

I have a collaboration planned with a friend who wants to shoot in small rural bars, which would involve a lot of people. I’m very nervous about going in, befriending people and then filming them so I’m putting it off, but she’s good at that. But it would be an interesting film to do.

I just a did a film with my ‘Acting Bad’ class called After Warhol, where we watched a few of the Warhol screen tests and then mimicked them. It’s not what he does but a manipulation; I got them to act as they thought a screen test would be in a Warhol sense, and then I recontextualised it so we could talk about how acting might not be screened the way you thought you acted. Especially today with these manipulations, and Hollywood films with collaging and green screens: groups of people going ‘aaaah!’, like that, and the monster isn’t even there. So it’s that idea. But it’s a nice little film, with an amazingly diverse group of students – 15, from all different cultures.

Then two years ago I made an installation from North on Evers (1991), which is 90-some minutes long and has 60 short portraits, each five to ten seconds long, of people I met when I did this motorcycle trip around the US, along with the landscapes I found. I simply slowed down the portraits at different rates so they’d all be about a minute long, and I could make a 60-minute silent film from the portraits of the 60 people. So I’ve started to film people again – there’s 60 people in that film, although usually just one person in the frame, sometimes two.

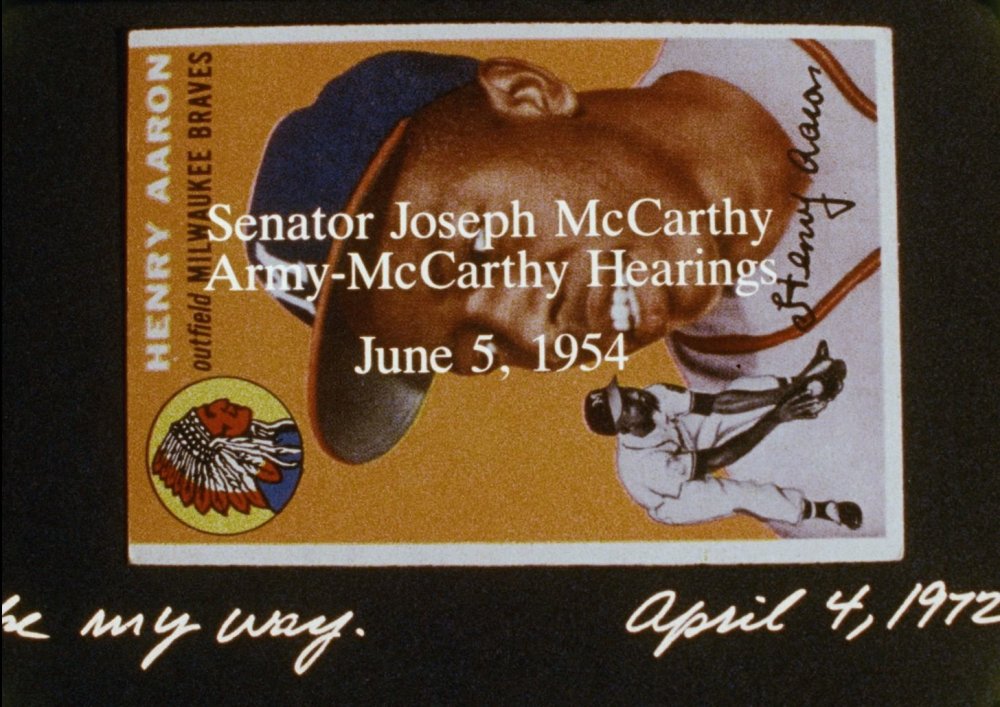

American Dreams: lost and found (1984)

I’ve also been thinking about using text in a film again, which I haven’t done for a while. And reading it myself. So I’m going in a lot of directions, but I am most uncomfortable dealing with people. I’m nervous like they are in front of the camera. That’s why when I shot 20 Cigarettes I got out of there so I wouldn’t spread this nervousness. And they were my friends, so it was easy; as far as going into a bar and filming strangers, that’s more stressful. So I think I’ll work on this voiceover film first.

Now, I just toured the four sub-level floors of storage here at the natural history museum [in Vienna]. The director asked me to come see it and was kind enough to take me down there. You go into the ‘Noah’s ark room’ where it’s all stuffed animals, two by two. Another is all pelts, and a whole wall of human skulls; all this stuff that’s out of view. He invited me back to make a film there. So I’m thinking I might like to do that.

It sounds like a Hitchcock scene.

It’s very bizarre. And when I was going round the museum I was watching the little kids look at stuff and got this idea of teaching a Listening and Seeing class in the museum with children. To look at the museum carefully with more patience and more time, and see if kids are even able to do that. And after three days of that, film them just looking. That could be nice.

The exhibits are pretty amazing. Some look like 50s drugstore furnishings, shelves and things behind glass. Others are more modern with video explanations of how the dinosaurs became extinct. I saw three little rocks found on the Earth that are from Mars – from a meteor explosion big enough to send rocks off Mars into the earth’s gravitation pull. That’s just unbelievable. So I’m keeping my eyes open for things.

El Valley Centro (2000)

I believe you’ve shown the California Trilogy [El Valley Centro (2000), Los (2001) and Sogobi (2002)] to school children before.

Yes, at this very progressive private school for kids – which was quite diverse in terms of class; some kids were muck poorer than others. Very enlightened kids; I don’t know if they were ten or 11 years old. It’s a really special school where your idea’s what’s important, and not whether you’re right or not but why you might have come to that conclusion.

The trilogy is made up of 105 shots, and they show one shot each time, so that means two or three screenings a week over the whole year of school. And each time they put up a video still of the place so over the year they fill their whole room with the 105 pictures, which helps them cross-reference shots when they’re looking at them three months later. And they can point at different things. I went to see them at the end of the year and they were so delighted for me to be there. They were worried for me because they thought some of the things I filmed were very dangerous – oil wells on fire and so on. So they wanted to know that if I was okay.

Now they’re doing it again. And this time the teacher is recording all their dialogues after each screening, and we’re going to do a book – a picture of each shot and the text of what they said that day. I think it’ll be one of the best books on my films, because they really studied every shot, and they’re at that age where they’re still so inquisitive. And the school really helps them want to learn. I wish I would have gone to a school like that.

Los (2001)

You’re about to mark a quarter of a century at CalArts. Are you still benefiting from teaching your Listening and Seeing class?

I stopped. For a number of reasons, mainly that there are too many lawyers in the world and the school’s nervous. Their solution was a lot of restrictions on what I could do, and things that would make the school not liable but nothing to make me not liable. That pissed me off.

I love CalArts, but it’s become an institution now, because of the pressure of outside agencies that want to regulate what we do. I don’t think any of the art schools in the US have gotten together to fight this interference to regulate the way art is taught and quantify everything and prove that you’re doing this. It’s all dumb stuff because it comes from other models and you don’t teach art that way. Hopefully the pendulum will swing against it, but it’s way too corporate for me.

And this is the school that was built against all those things. In the classroom it actually still functions the way it always did: we get really good students and good work; I’m inspired. And the diversity is increasing. It’s not quite there for income level but it certainly is for different colours, religious backgrounds and sexual preferences. It’s a utopian situation with the problems of trying to remain utopian, because the outside world comes in; we all live and come from it. But those are problems I like to negotiate, rather than these corporate problems of law and being afraid of being sued.

Sogobi (2002)

One more question. Your work has been inextricably bound up with America, but your screenings have taken you all across the world. After Ruhr, will you ever film again abroad?

I made Ruhr because that burg [Duisburg] reminded me so much of Milwaukee. So even though I made the film in Germany it was really finding things that spoke to my own background.

I didn’t think I’d want to travel again because it’s hard to fly with equipment, but if I do something here at this museum I might a collaboration and then it would be easier, because two people could carry the equipment. And this is just a surreal place, so it would be interesting to make a surreal film, which I haven’t done. But as a reality, because it would be all real, all this stuff… rocks from Mars.

A sci-fact film?

Yeah. All right, I quit.

-

Sight & Sound: the October 2013 issue

In this issue: 40 years of The Wicker Man, plus The Great Beauty, Slavoj Žižek on cinema’s dark secrets, Claude Sautet’s noir classic...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.