Web exclusive

Ruhr (2009)

I had planned to see Ruhr – landscape listener/seer James Benning’s much anticipated first foray into HD digital video-making, and not coincidentally his first work shot outside the USA – at the Rotterdam Film Festival, but circumstances on my first morning made it the only possible choice. I woke to an attack of blepharitis – a condition that causes clogging of the eyelash roots, thereby blocking oil-secretion glands and inflaming the eyelids. Despite what you may have read in Nick Cave’s novel The Death of Bunny Monroe, blepharitis does not threaten sight, it just makes your eyes itch, your sight smeary and your lids feel like doormats. It can also make you look as if you’ve not slept (see Christopher Hitchens, a fellow sufferer), which means that when the Sundancers arrive you can at least blend in.

Though a hot flannel eased the pain somewhat, the prim girl at the counter of the local pharmacist (hair tied back, briskly unhelpful) could not give me the anti-infection eye drops freely available in the UK, so I needed a first film I could cope with. The fact that Ruhr consists of just seven shots made it the sufferer’s choice. I could blink as much as I liked without missing too much, and it would force me to be contemplative. What follows are some of the ordinary subjective observations that floated through my mind.

Part 1

Shot 1: A lay-by in a tunnel

It’s obviously a hi-def digital image but is it monochrome? There’s a yellowish cast beneath the greys, but it’s hard to tell if it’s meant to be there. With the zig-zag of strip lighting overhead, the conjunction of lines make look it like a bent-metal perspective drawing, but it’s palpably a tunnel in an industrial area.

Echoey road noise rumbles. I feel like my eyelashes are sweeping up the fag-ends and crushed wrappings in the gutter. Approaching vehicle noise. Wow! Look at that sudden colour: a vivid red van, the windscreen’s gorgeous blue-green too good to be true. Has Benning manipulated the hues? Seems like. You soon get into the rise-and-fall rhythm of vehicles coming through. The big clanking truck has a dangerous-sounding, shifting load.

You wonder how the briefly glimpsed drivers are reacting to sudden sight of a camera in an underpass. There’s enough suspense to keep you looking. Then there’s the comic surprise of the well-padded cyclist who zips in from behind, camera left, and off into the void round the corner. He doesn’t look back (did some others, I wonder, ruining other takes?).

When you see the wind rolling a hard-to-identify object (a wodge of crushed paper is my guess) slowly towards the camera, you know the shot will last until the object has come to rest or is nearly out of the frame.

Shot 2: A steel foundry

A saw-tooth pole-rolling machine is in the foreground, hustling a few steel poles ranged away from us, but not really moving them much. The Ruhr is known as the industrial heart of Germany. Benning’s parents came from there. I know of it, sadly, because it was the primary target for allied bombers in World War II. On schoolboy war maps it was always a cross-hatched blob signifying a future blot on the landscape.

Here I fix at first on the peculiar shuffling movement of the saw teeth and on the half-obscured number painted on the machine’s side. In the background, after a while, a number of red-hot poles move in horizontally stage left, as gaudy as a chorus row. Trying not to jam my fists into my eye sockets, I wonder how close you can place a camera to red-hot steel rods, and whether there are European safety laws that prevent Benning from being too Hemingway about it.

A lifting device above the hot rods descends to pick one up, lifts and moves it towards us, then places it back down on a conveyor in the middle ground. For it’s next trick it goes back and picks up another to place next to the first. Then those two are wheeled away and the whole business is repeated. As the Hollywood actor at the Oscars says, “Rock ’n’ roll, phew!”

Shot 3: The sky through trees

Autumnal tree branches silhouetted black against a white sky with all the brilliance digital can bring. The shift to the relatively bucolic is pronounced, if brief. Wind soughs and branches sway and then a powerful roaring and whistling sound builds – a low-flying aircraft sweeps through the frame.

But you have to wait perhaps 30 seconds until the revelatory event, when the jet’s backdraft finally shakes the trees and a cascade of leaves falls. It’s most spectacular the first time, so you have to wonder how Benning got the timing so right. Did he start the day with full leafy trees and end with bare ones? Is there only one particular day of the year when this shot can be as perfect as it seems?

Shot 4: A mosque

A hip-height shot from the back of a mosque catches the crowd kneeling and bowing at given moments while prayers are being read. The shock comes when they all stand up and the jackets of the two closest men occlude the general view. They seem close. Is the camera enclosed, or vulnerable?

This mosque could be anywhere in Europe, including the UK. I suppose, it being the Ruhr, that they’re probably Turkish. They sit down again. When they bow low, the array of rear ends makes me smile then suppress the smile.

At the conclusion of prayers, the faithful throng moves towards and around the camera as if it were a pillar. Their sincerity makes me feel guilty about smiling. One sharp young boy looks into the lens as he passes. Others, less organised, come in for their own unled prayers. I can’t help selfishly wanting them to pray for a miracle cure for blepharitis. Maybe I should go to see Lourdes.

Shot 5: The graffiti girder

A man in overalls, gloves and a welder’s-type face mask is cleaning graffiti from a huge flyover support (we must assume, since what it supports is out of sight) of slightly rusted steel with a strange machine that seems to burn and blast the paint simultaneously. It is a laborious process; at the shot’s beginning he has cleared only a band about a metre wide two thirds of the way across the support.

This piece makes me flinch in sympathy at the idea of all these lead paint particles flying in the air. The worker is removing quite inventive graffiti, including cartoon figures and large hearts – work reminiscent of major American pop art pieces. He seems to be taking an aesthetic approach to the removal. It’s like watching a film of a painter at work run backwards. At the rate he goes, it’ll probably take him a whole day. The Ruhr’s Banksies will no doubt be back tomorrow. Sisyphus eat your heart out.

Ruhr (2009)

Shot 6: A street

We are looking down a short residential street. Despite the roar of passing traffic from an autobahn bridge in the background something convinces me that this street scene is taking place on a Sunday. Again the colours are gorgeous, that windscreen blue, the honey colour of the house on the left.

People come and go – do they know someone is filming so that they shyly keep out of the way unless they have something essential to do, is it very cold or is an important football match keeping them indoors?

Cars mooch along and turn out of view. Time for the big shot.

Part 2

Shot 7: The chimney

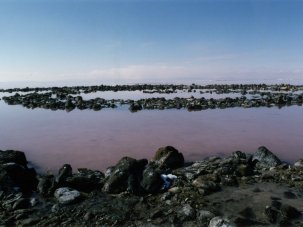

It is the magic hour and centre-frame is a huge cubic construction looking like a Chinese siege tower girdled with walkways. Out of the top smoke, steam or some other gas rises gently, touched with a creamy orange by the low sun. Soon we hear strange, distant bleating sirens that last perhaps as much as a minute; then, very gradually, a powerful effusion of smoke begins to gush from the top. Valves in the chimney’s sides allow more to seethe upwards so that soon the tower is wreathed in twists of smoke like candy floss.

The complete shot lasts for around an hour, during which time the smoke cycle happens many times, the sun goes slowly down and what was a front-lit shot becomes backlit, making the chimney look like a machine out of Hieronymus Bosch via Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings.

I lasted almost to the end of this exquisitely and unexpectedly magnificent experience before the urge to properly treat my eyes finally won out. Damn my eyes.

Nick James’ full Rotterdam Film Festival report will appear in the April 2010 issue of Sight & Sound.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.