He’s got the look: Harry Langdon in The Strong Man (1926)

What was I supposed to do with that? Knowing I was keen on films, someone had given me a 200ft roll of nitrate. It showed a scene from Rupert of Hentzau, made in 1913. I had heard that old films were printed on cellulose nitrate stock, which was highly inflammable. What’s more, the industry was still using it. It was 1950; I was 12 years old, and enjoyed staging battles with my friends on the acres of bombed sites that surrounded my home in North London. I placed this roll in a paper bag, climbed to the roof of a bombed building and when my pals passed beneath, I lit the fuse and dropped it. It exploded most satisfactorilly. But I could have kicked myself when I needed the sequence for a documentary in 1996. That roll was all that was left of an important film – and the images on the reel had looked most impressive.

Far more exciting than burning nitrate was watching it on the screen. I remember at the National Film Theatre showing a dim 16mm dupe of a Colleen Moore comedy called Orchids and Ermine (1927). It was the usual thing that laboratories subjected us to in the 1960s. Then the projectionist switched over to the same scene in original nitrate. The audience gasped. The difference was indeed breathtaking. The 16mm barely registered. The 35mm looked stereoscopic – you felt you could walk into it.

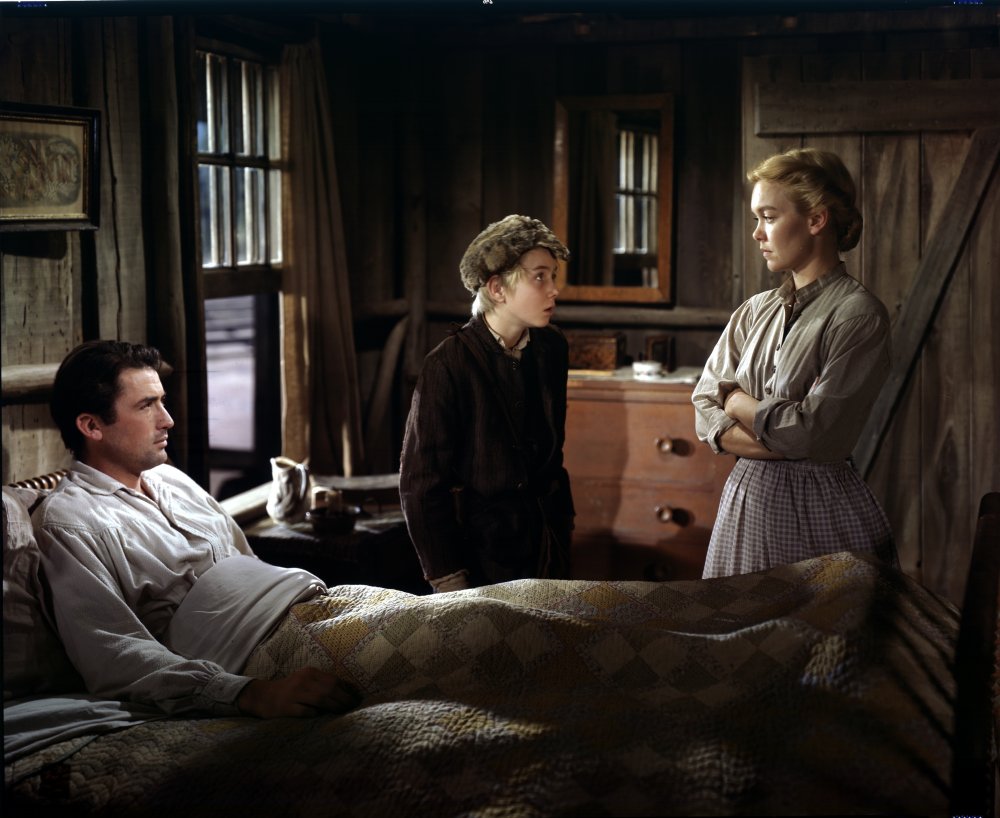

I first became aware of the beauty of nitrate when the Museum of Modern Art sent a print of The Strong Man (1926) to the National Film Theatre in the 1950s. Expecting the standard dupe of the time, we were treated to a gorgeous tinted print, identical to what people saw in 1927 – it was bright, steady and sharp as a tack. I had become a connoisseur of print quality because my first sight of a moving picture had been a dreadful home movie made by Dr Barnardo’s and shown to us kids at boarding school. I knew nothing about films – had never even seen one – but I felt instinctively that this was Bad. When I finally went to a cinema, around 1943, Snow White was accompanied by a newsreel. Four naval officers were walking towards camera. The superb black and white photography remains in my mind to this day. Snow White’s Technicolor animation impressed me less than that one rich image.

Golden years: Clarence Brown’s The Yearling (1946)

My enthusiasm for early films was sparked at another school, where once a term we saw a talkie; the rest of the time we saw silents, hired from Wallace Heaton film library. Enthralled by these, I beseeched my parents for a projector and soon became an avid collector myself. The British Film Institute used to show silents at the French Institute in those pre-National Film Theatre days. But what miserable prints! Oily, soupy, dupey, there was absolutely nothing to commend them.

Without Bert Langdon, a collector in Camden Town who used to show original nitrate prints every Saturday night, I might have abandoned my interest. He cranked his projector with one hand and played gramophone records with the other. Thus we had stunning picture quality and orchestral accompaniment. How he managed to hold on to those films I cannot imagine. He lived in a council flat, and he had been there all through the war. His collection included 86,000ft of extracts. Had all that celluloid been hit by incendiaries, the entire terrace would have gone up.

Bert Langdon wouldn’t admit it, but he was slightly afraid of nitrate. He knew he should have proper ventilation yet he didn’t even open a window and kept incense burning throughout the show. To minimise the fire risk, he limited his lamp output to 100 watt. This was a shame because it reduced the impact of the films. Nonetheless, the quality was superb and we could see all the tints and tones.

Alexandre Volkoff’s Pathécolor Casanova (1927)

I hadn’t realised the old films were so elaborately tinted and not only that, the early French had a stencil system called Pathécolor which could be incredibly beautiful. Those evenings watching unique nitrate prints set a new standard and made me paranoid about print quality. I couldn’t so much as watch 8mm. But sell me a 16mm print from the Kodascope library – you could tell these by the smell of camphor – and I knew I had the nearest to nitrate, for the prints were uncannily sharp. Original 35mm prints were hard to see outside the NFT and Bert Langdon’s, although some fleapit would make up a Sunday programme somewhere from old nitrate prints.

But rapidly they fell into obsolescence. People became paranoid about them. Fire officers took sadistic delight in relating horror stories in which nitrate burned under water, producing its own oxygen. “Nonsense,” we veterans retorted. “So long as you treat it properly, it is no more dangerous than the petrol in your car.” But even archives, once they’d made their copies, burned the nitrate. Many of them still do. How desperately grateful we would be, in this age of DVD and HD, to have access again to those exquisite prints…

My wife was deeply impressed by the nitrate we used to see at the Fox studios, in Los Angeles, when the great Murnau and Borzage and Hawks films were dug out of the vaults. That was 40 years ago, but even today, when you get that incredibly intense light right after a rainstorm, she will break into a seraphic smile and say “Nitrate weather again.”

And yet I remember when a West End cinema was showing a nitrate print of a Garbo film – out of focus. A slight twist of the lens and it would have looked superb. I called an usher and asked him to contact the projectionist. The film was being ruined. “Oh, that,” he said, gesturing with contempt. “That’s an old film. Nothing you can do with it.”

-

The 100 Greatest Films of All Time 2012

In our biggest ever film critics’ poll, the list of best movies ever made has a new top film, ending the 50-year reign of Citizen Kane.

Wednesday 1 August 2012

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.