It’s an image like the phoenix from the flames: a charred, dust-caked roll of 35mm film balanced on a spade, dug out of the black and frozen earth. What once danced, flickered and dazzled, then was lost, now promises to light up again, spilling its treasures like Aladdin’s genie. Though as viewers of Bill Morrison’s necromantic digs through the film archives since Decasia (2002) will know, the interceding years will have left their own marks on the images, making palimpsests of these remains.

Dawson City, Frozen Time is available on Blu-ray and DVD from Second Run in the UK, and from Kino Lorber in the US. It is available to rent online from Second Run On Demand.

Film and Notfilm are available on DVD from the BFI in the UK, and from Milestone in the US.

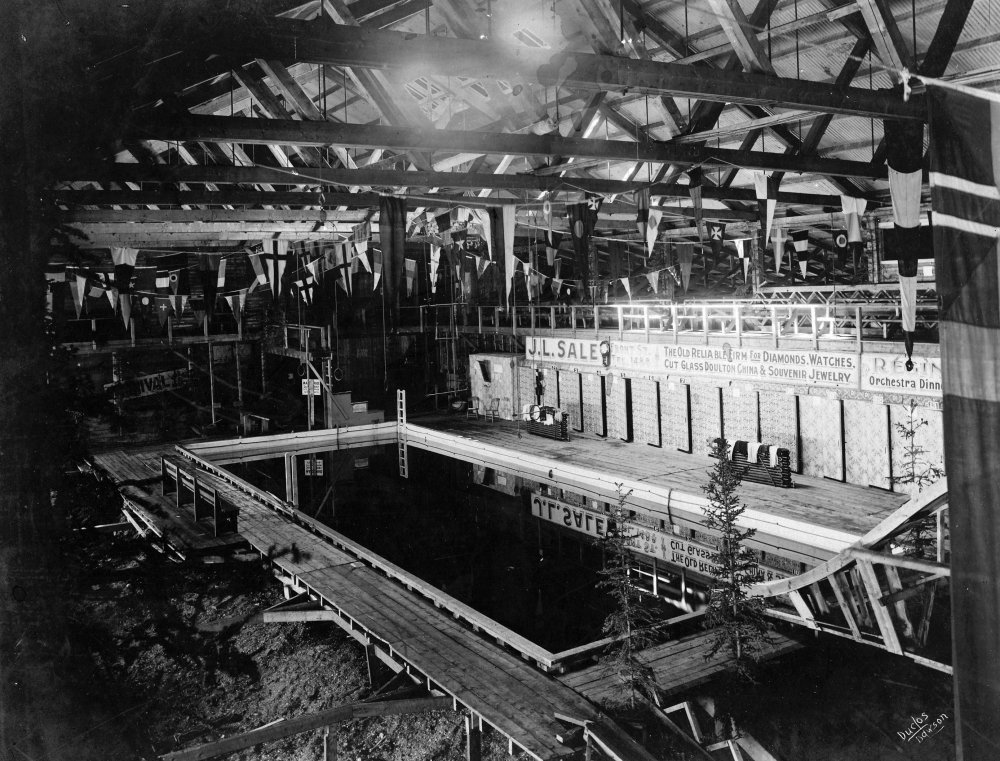

The Dawson City Film Find was turned up in 1978 when a bulldozer in this outpost in the Yukon Valley set about the remains of an ice-hockey rink that had once covered a swimming pool. In fact, kids playing outside the Dawson Amateur Athletic Association, which had once also hosted one of the town’s three movie theatres, had long reported strips of film growing out of the ground – as had a local newspaper in 1939 – but faced with the emergence of more than 500 reels, the diggers were stopped, local archivists called in, and ultimately the thawing collection was driven at speed to Ottawa, to be divided between Library and Archives Canada and the Library of Congress.

Morrison unspools this story at pace from the end – he’s even able to incorporate a TV interview with himself about the project, thanks to some publicity for his in-progress excavations of the Film Find archives – because the beginning is even better: Dawson was a Klondike Gold Rush boom town, built on treasures underfoot, and a bust town equally, trampled over then forsaken by our civilisation’s stampeding prospectors.

Dawson City, Frozen Time (2016)

It was born in sin – quickly displacing the Han First Nation fishing camp of Tr’ochëk after George Carmack and Skookum Jim struck gold in 1896 – and burgeoned accordingly as 30,000 arrived over the Chilkoot Pass two years later. Morrison’s cast of hustlers and gawkers includes Fred Trump, Donald’s grandfather, who founded the family fortune in a waystation brothel; future Hollywood theatre moguls Alexander Pantages and Sid Grauman; scandal-fated filmmakers William Desmond Taylor and Roscoe ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle; and writers Jack London and (latterly) Robert Service. The party blew out just as quickly: barely a quarter of the immigrants remained by 1899, and those who were to settle down and build saw fires gut Dawson’s business district every year for the first nine years, while the town’s gold-mining concessions were progressively consolidated, automated, plundered.

All of this parallels the contemporaneous story of early film, with its pioneers and entrepreneurs, cogs and cycles, fads and flameouts, not least thanks to the flammability of early nitrate film. Morrison seems to punctuate his film with the burnings-down, down the years, of Dawson’s three cinemas. But there are other timelines at play too – business-cyclical, cultural, generational, civilisational. Foremost, of course, is the arc of the rediscovered footage we are watching. As it was for many of the Gold Rush speculators, Dawson City was a point of no return for the films that reached it, often two or three years after their outset, at the end of the Pacific coastal distribution line: like films lost and found in New Zealand, distributors saw no profit in repatriating the worn prints. Most, it seems fair to say, will not have been used as swimming pool filler; they’ll be getting a geological engraving at the bottom of the Yukon River.

The Dawson Amateur Athletics Association’s swimming pool turned ice rink in Dawson City, Frozen Time

The materials he has, though, Morrison makes sing – greatly abetted by the majestically glacial compositions of Sigur Rós collaborator Alex Somers and his brother Jónsi’s spryly animating sound design. Shots from the Dawson Find are repurposed, remixed, made to talk metonymically about the history behind them and reflexively about the nature of their medium while Morrison narrates in silent supertitles. There are compilation sequences that remind me of the meta cine-montages in Charlie Lyne’s Beyond Clueless (2014), indexing particular figures or movements that recur across the found films. Perhaps the reason Morrison’s sidetrack into uncovered glimpses of the 1919 baseball World Series feels flat is not so much its parochialism as its literalism, where so much of the footage gains layers of metaphor. Compare with the sequence about the invention of the newsreel illustrated not by the same but with a montage of characters diving in and out of their newspapers.

Again, the film acknowledges other strata of media, with their own rich stories: much of its more literal documentary power comes from Eric A. Hegg’s astounding photographs of the Klondike Stampede. Two thousand of Hegg’s glass-plate negatives turned up in the cavity walls of an old cabin in Dawson in 1951, and narrowly missed being scraped clean for greenhouse glass by their first finder. They gave rise to Colin Low and Wolf Koenig’s 1957 documentary City of Gold, a portrait of Gold Rush-era Dawson City narrated by writer and Klondike veteran Pierre Berton, which won the Cannes short film Palme d’Or that year and which Morrison credits with inventing the ‘Ken Burns effect’ of panning across stills photos.

Dawson City, Frozen Time (2016)

And of course there’s Chaplin’s 1925 The Gold Rush, alongside Clarence Brown’s Robert Service adaptation The Trail of ’98 (1928), a first wave of fantasias of the frontier packaged for a new generation by a now-consolidated Hollywood. Morrison’s field archaeology through all this is dazzling and precious, but it’s also sensitive and mournful, attuned to the ravages of capitalist culture – gluttonous, amnesiac – as well as the march of time. The film is a lesson in the contingencies of remembering, the precarity of memory; its story of chance finds is underwritten by Morrison’s own work in the Dawson Film Find archive, a seam of cinema still barely explored more than three decades after its preliminary rescue. As he puts it in a supplementary interview on Second Run’s disc, the materials were “viewable but unviewed”. If a film lies in the permafrost – or sits in an archive and nobody watches it, does it record a memory?

~

Over the past two decades, inspired perhaps by the passing of physical film or the coming climate meltdown, film artists have increasingly taken to documenting our media flotsam and civilisational cast-offs in a mode of portentous media archaeology. The dead-architectural film – Nikolas Geyrhalter’s Homo Sapiens (2016), Salomé Lamas’s Extinction (2018), a litany of portraits of hollowed-out Detroit – has been one obvious draw.

But there are less monumental, more fleeting subjects. Thom Andersen is one of the masters of this mode – with an emphasis not on the sentimental but the radical aspects of nostalgia. His 16mm musical featurette Get Out of the Car (2010) evokes lost Los Angeles through a vernacular medley of fraying billboards, pop singles and demolished sites of cultural importance. His most recent video essay The Thoughts That Once We Had collates a personal scrapbook of treasured, affirmative movie moments through the prism or pretext of an illustration of Gilles Deleuze’s twin books of writing on cinema (with their emphasis on cinema’s historical turn from depictions of action to depictions of time).

Patricio Guzmán and Rithy Panh, guardians and threnodists of their countries’ memories on film, have also turned towards media – its testimonies, its elisions – in their recent films. Guzmán’s The Pearl Button (2015) in particular echoes Dawson City: Frozen Time in its aqueous motifs and account of extermination at the end of the world (the indigenous Selk’nam were imprisoned on Patagonia’s Dawson Island as, later, were Allende government ministers).

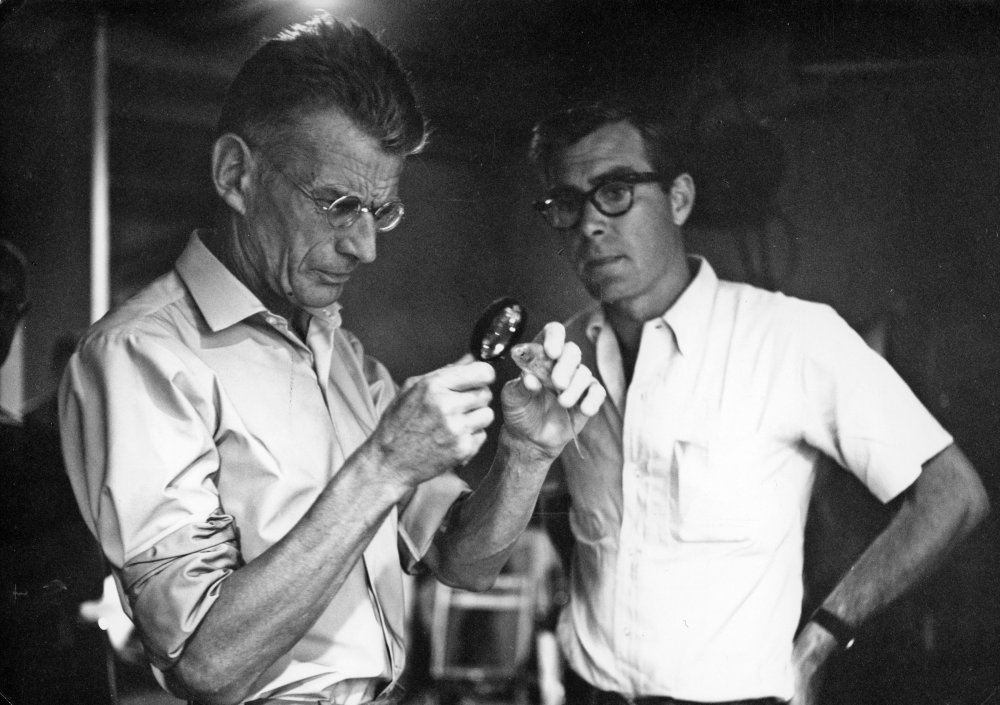

Samuel Beckett in Notfilm

Ross Lipman’s Notfilm (2015), released on disc by both Milestone and the BFI in the mists of 2017, is another dig through layers of film history, though here the act of reclamation ironically works against the spirit of its subject matter. Structured as an extended making-of about Samuel Beckett’s sole foray into filmmaking, the 20-minute Buster Keaton meta experiment Film (1965), it spins a historical and philosophical yarn which connects Keaton’s own endlessly modern cinema with the parallel investigations in the USSR of Dziga Vertov (whose brother Boris Kaufman shot Film), and with a media phenomenology inspired by the idealist, immaterialist philosophy of the 18th-century empiricist George Berkeley, Beckett’s Irish forebear.

Berkeley asserted the absolutism of our sensory awareness with his maxim esse est percipi – to be is to be perceived; it makes no sense to talk of matter independent of a perceiving mind. Beckett, with what Lipman calls his “poetics of the void”, wrote the film as a deliberately naive inversion of Berkeley, distilling an existential dread: if existence is in the eye of a beholder then bring on occlusion. Thus he diagrammed Film as an implacable chase movie between Keaton’s O, the unwilling camera object who attempts to deflect all possible observers – passers-by, his pets, an image of God – and the relentless camera eye E, the ultimate observer, revealed to be a mirror of his own self-consciousness.

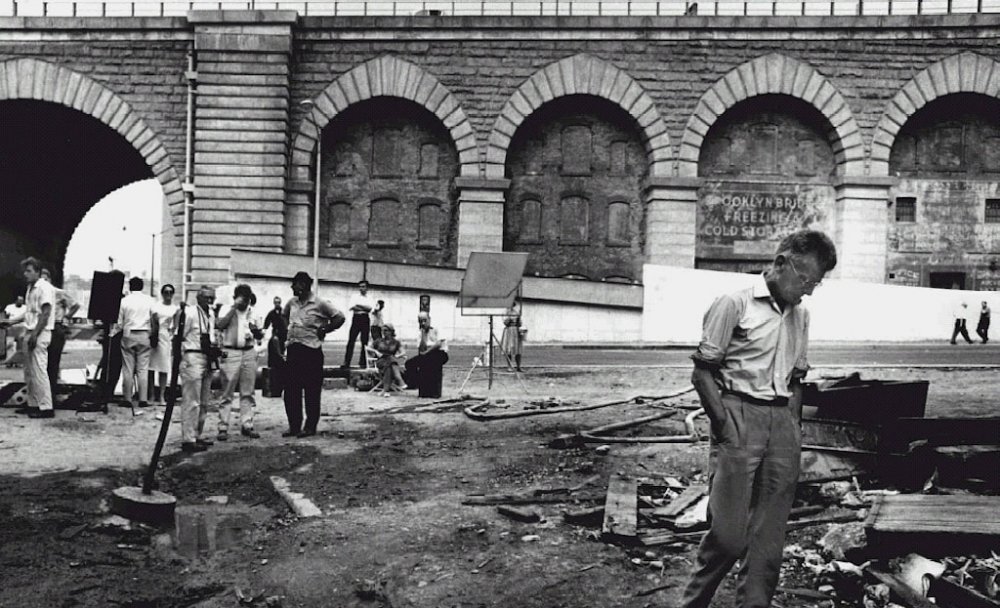

Beckett on the location of Film

On the face of itself, Film is an awkward piece of work, rudimentary as a riddle and slow on gags – and Lipman explores the behind-the-scenes reasons, not least a split on-set between the amateur filmmaking intellectuals and the gruff pros like Keaton. But as the raw material for Notfilm, it is a treasure. Lipman first discovered and studied Beckett’s film as a student (studying under the founding film theorist Rudolph Arnheim), and you could diagram his relationship to it like E chasing the reluctant O. Beckett disdained the results of his experiment; Lipman became a UCLA archivist, restored the film and tracked down its outtakes. Beckett shunned the camera (he found its gaze “a personal wound”, we’re told; Kevin Brownlow recalls his fear of undercover cameras and being stalked by press, and a summons to a meeting with the instruction “no camera or tape recorder”); Lipman deposes friends and colleagues of Beckett’s and Keaton’s – Jean Schneider, Billie Whitelaw, Haskel Wexler, James Karen – and plays us an illicit, under-the-table recording of a script meeting made by the film’s producer, Grove Press’s Barney Rosset.

As film criticism, Lipman’s “kino essay” is a joy, opening up both Beckett’s and Keaton’s works and elucidating the uncanny overlaps between them (with liberal use of Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera as well as The Cameraman and the rest of Keaton’s oeuvre), underpinned by Mihály Víg’s elegiac piano trio score. And it teases some of the unnerving implications of Berkeley’s always counter-common-sensical philosophy, with its uncanny anticipation of our post-cinematic, post-materialist attention economy, whose secrets will not survive in the snow.

-

The 100 Greatest Films of All Time 2012

In our biggest ever film critics’ poll, the list of best movies ever made has a new top film, ending the 50-year reign of Citizen Kane.

Wednesday 1 August 2012

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.