from our July 2013 issue

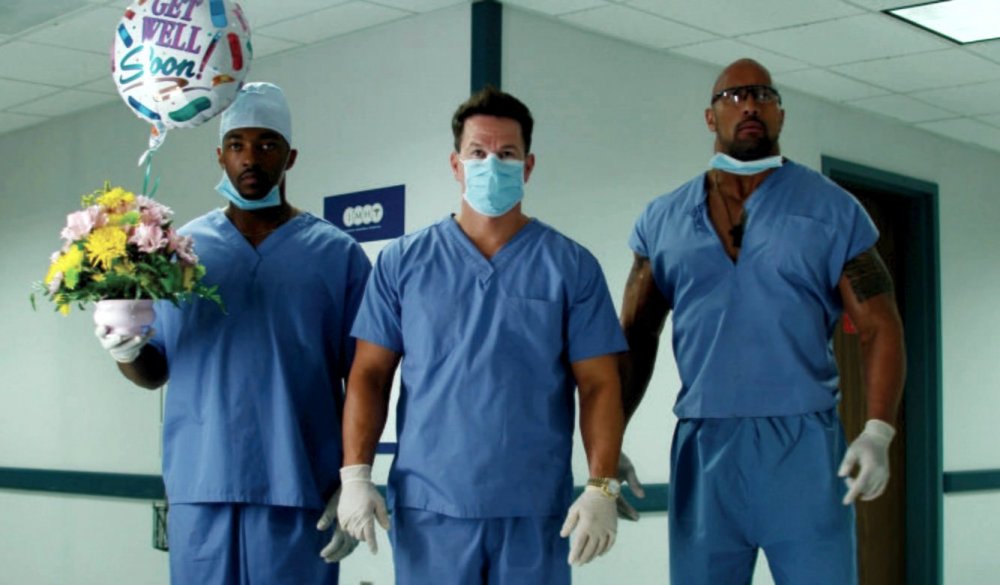

Bad boys: Anthony Mackie, Mark Wahlberg and Dwayne Johnson

Michael Bay is buff. There is a picture of him, taken in the Playboy Mansion, his home away from home, in 2007. He has his chest exposed. A big gold medallion is nestled beneath the overhang of his toned pecs. He stands to the right of the June 2004 centrefold; on her other side is Mike Tyson. The corner of Bay’s mouth is jacked up in a crooked smile. This is the life!

| USA 2013 Certificate 15 129m 25s Crew Cast Dolby Digital/Datasat Distributor Paramount Pictures UK |

Prime architect of the staggeringly profitable Transformers franchise, Bay has done very well for himself, with a net worth estimated at $400 million. This hasn’t necessarily exchanged into cultural capital. Bay’s name is used, mostly accurately, as a byword for everything that is wrong with Hollywood: the pandering to the basest impulses of adolescent males, the heedless profligacy, the blunt-force-trauma style, the nihilistic violence and almost complete absence of any human values. But it must be admitted that Bay has some singular kind of insight into the zeitgeist and Pain & Gain, his tenth feature as director, has become the flashpoint for a critical reckoning. Michael Bay: vulgar auteur, or common philistine?

What Bay has is everything that Daniel Lugo, the protagonist of Pain & Gain and one of its multiple narrators, wants. The film’s events are based on a series of articles written by Pete Collins for the Miami New Times, about the exploits of a gang who ran a kidnapping and extortion racket out of that city’s Sun Gym. Lugo managed both racket and gym until finally brought down in 1995 – the same year that Bay’s Miami-set feature debut Bad Boys was released. Lugo is played by Mark Wahlberg, whose voice runs into a breathless, thin whine when he’s exasperated or confused, which he often is here. Wahlberg is resuscitating the dull-witted Dirk Diggler of Boogie Nights (1997), the simpleton who believes that his physical gifts have equipped him for an extraordinary destiny.

Bay shoots from awed low angles which make his buffed cast – Anthony Mackie and Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson round out the gang – appear as swaggering gods, while the script emphasises their very human foolishness. Bay’s images are the Sun Gym gang’s ideal of themselves, forever flexing in a mirror in their mind’s eye; the awful truth is in the facts of the story. The film’s overarching theme, the chasm between self-image and actuality, is summed up in an exchange between Lugo and Doyle (Johnson) when the latter stumbles into a wedding party, coked up, his face painted green by an exploding dye pack in a heisted cash bag from an armoured car, his toe shot off by pursuing police. “You look like shit,” says Lugo. “I feel like I look great,” says Doyle.

There are manic passages in Pain & Gain when filmmaker and material seem to fit hand in glove. Who better to deal with crass, acquisitive aspiration than one who has made his living by selling the same values? Bay came to features from commercials and music videos. His Bad Boys was followed by ever larger, ever more bombastic spectacles – The Rock, Armageddon, Pearl Harbor – monumentally shallow works whose nothing-succeeds-like-excess style matched the false-bottomed super-prosperity of the pre-9/11 bubble-economy years, the period in which Pain & Gain lays its scene.

And Pain & Gain does feel very 1990s – not merely in the way that it conjures up the era’s high-end lifestyle porn, but in how it plays as a callback to the cycle of attitudinal, ‘dark’ caper comedies that proliferated around the time Bay was first making the scene, when Quentin Tarantino’s breakthrough success began a ‘black comedy’ boom stretching between, say, Danny Boyle’s Shallow Grave (1994) and Peter Berg’s Very Bad Things (1998).

More than anything, though, Pain & Gain has the mark of the Brothers Coen on it, concerning as it does a Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight who’ve gotten in way over their heads. Marge Gunderson’s “There’s more to life than a little money, you know” in Fargo is even echoed in a moral summing-up by Ed Harris’s PI, an ode to ‘simple things’ — easy for a leathern WASP to appreciate, given the privileged piece of real estate he occupies.

The script, by Christopher Markus and Stephen McFeely, intuits a great deal about race, class and longing for mobility in America. Lugo’s dormant ambition is first activated by Jonny Wu, a motivational speaker who asks his acolytes to identify themselves as either doers or don’ters.

The character, played by Ken Jeong, is based on real personality Tommy Vu. Here, Vu’s cutthroat go-getter rhetoric is lampooned – though in Bay’s The Rock a similar worldview was iterated for all time in fratboy-quotable fashion: “Your best? Losers always whine about their best. Winners go home and fuck the prom queen.”

Is this rank hypocrisy? Is it a mistake to credit Bay with irony, with a capacity to embrace intentionally the same ambiguity that Steven Soderbergh recently bemoaned the loss of in American movies?

It sure feels like it every time Bay betrays his bad-boy self-satisfaction in rendering nasty true-crime material as farce, in the deflationary soundtrack FX that might as well be the classic “Waaaa waaa waaaaaaaaah” accompanying egg-on-their-faces look-at-these-dummies punchlines.

But while Pain & Gain often frustrates, Bay’s overwhelming cinematic sense is undeniable – he’s swallowed the dictionary of film grammar and there are moments when the movie’s sunstroke delirium and iconographic flair recall the Mikhail Kalatozov of I Am Cuba (1964). Deeply conflicted and fitfully brilliant, Pain & Gain may not be the movie of the moment that cinephiles wanted – certainly not from this smirking, perma-tanned messenger – but it’s the one we’ve got.