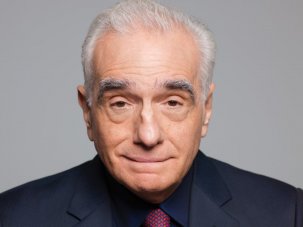

There is a sense of nostalgia and of letting go about The Irishman, the first and probably the last organised crime film made by Martin Scorsese to star not only his long-time colleagues Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci and Harvey Keitel but also genre icon Al Pacino, whom Scorsese has never previously directed. (The old goodfellas’ faces, especially De Niro’s, were expensively de-aged by facial-recognition technology for the scenes in which their characters are younger.)

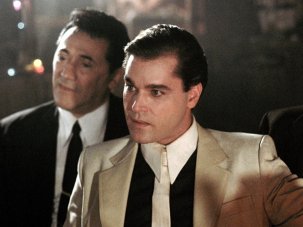

If this is a goodbye, then Scorsese has a little intertextual fun with it. As the eponymous Mob and Teamsters labour union hitman and courier Frank Sheeran (a real-life figure, who died in 2003 aged 83), De Niro gets to destroy a fleet of chequered yellow cabs like the one he drove in Taxi Driver. Shortly before Sheeran shoots mobster Crazy Joe Gallo outside Umberto’s Clam House in Little Italy in 1972, Gallo celebrates his birthday at the Copacabana club, a Raging Bull location and site of Goodfellas’ weaving Steadicam shot (the most famous Scorsese shot of all), where comic Don Rickles (Jim Norton) is performing. Had Rickles accepted Gallo’s invitation to Umberto’s that night, he may never have lived to be directed by Scorsese in Casino in 1995.

It is not Scorsese and Mafia lore that make The Irishman a requiem, however, but the way it morphs from an ebullient, sprawling comedy-drama about the outsider Sheeran’s three-decade involvement with La Cosa Nostra into a mournful reflection on friendship, betrayal and the unassuaged guilt men take to their graves. Unconcerned with law and order (Mob life, with its code of duty and loyalty, is a social metaphor for Scorsese, as it is a matter of family dynamics for Francis Ford Coppola in The Godfather movies), the film is a morality play that forces Sheeran to confront an irresolvable conflict of interests. This resonates more than screenwriter Steven Zaillian’s adherence to Sheeran’s ambiguously worded confession – made to Charles Brandt, author of I Heard You Paint Houses, the film’s source – that he assassinated the powerful former Teamsters boss Jimmy Hoffa (Pacino) on 30 July 1975.

In his mid-thirties, Sheeran is mentored by the Northeastern Pennsylvania Mafia boss Russell Bufalino (Pesci), who recommends him to Hoffa as an enforcer and minder. Hoffa puts a touching level of trust in Sheeran. When they share a hotel suite, Hoffa wears his pyjamas in the fully clothed Sheeran’s presence, and leaves his bedroom’s sliding doors ajar, a targeted man’s gesture of faith in his bodyguard’s protectiveness.

Twenty-eight years after he murders Hoffa, Sheeran leaves the door of his care-home room open on his last night alive. The echo is unreadable: is this an old man’s habit, a survivor trusting in a protective god, or his inviting in of death? Though the ailing Sheeran won’t admit to visiting FBI men that he killed Hoffa – even for the sake of Hoffa’s children – or express remorse to a priest, he is clearly haunted by the episode, and especially by having telephoned Hoffa’s widow Jo (Welker White) to tell her that her husband would soon show up.

The film’s epic battle is fought not between Hoffa and the mobsters he threatens to expose posthumously if they whack him, but between Sheeran and his conscience, charged as he is by the man he reveres most with the Cain-like murder of a man he admires almost as much. Sheeran gleans at his Teamsters appreciation dinner, where Hoffa makes the keynote speech and presents him with a diamond-encrusted gold watch, that Hoffa is signing his own death warrant by seeking to regain the Teamsters presidency and cut off the Mob. But when Sheeran learns that he must kill him, he is blindsided by being cast as Brutus.

Credit: Courtesy of Netflix

There ensues a long sequence – depicting the two flights and four car rides it takes Sheeran to travel to and from the house where he matter-of-factly shoots Hoffa twice in the back of the head – that elicits some of the most brilliantly opaque acting in De Niro’s career. The Michigan countryside beneath the single passenger plane that carries Sheeran to Detroit and the colourless middle-class suburbs he drives through are shot with chilling blandness by Scorsese’s cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto (The Wolf of Wall Street, Silence).

USA 2019

3h 29min

Director Martin Scorsese

Cast

Frank Sheeran Robert De Niro

Peggy Sheeran Anna Paquin

Jimmy Hoffa Al Pacino

Russell Bufalino Joe Pesci

Mary Sheeran Aleksa Palladino

Chuckie O’Brien Jesse Plemons

Angelo Bruno Harvey Keitel

Felix ‘Skinny Razor’ DiTullio Bobby Cannavale

Anthony Provenzano Stephen Graham

Robert F. Kennedy Jack Huston

Anthony Salerno Domenick Lombardozzi

Carrie Bufalino Kathrine Narducci

Bill Bufalino Ray Romano

Joseph ‘Crazy Joe’ Gallo Sebastian Maniscalco

Allen Dorfman Jake Hoffman

The Manicurist Sharon Pfeiffer

Irene Sheeran Stephanie Kurtzuba

UK release date 1 November 2019 (limited cinema release), then 29 November 2019 online

Distributor Netflix

► Trailer

Humdrum on the surface, roiling underneath, this passage is The Irishman’s extended low-key climax, and it concentrates the film’s proposition that Mafia violence is no longer the cinematic domain of Sicilian hoods in black shirts and white ties or Brooklyn wise guys in shiny suits. In The Irishman, it is conducted by weary but efficient middle-aged men who stay in Howard Johnson motels, go bowling with their wives and tell sweet jokes to little girls, as Bufalino does to Peggy Sheeran (played as a child by Lucy Gallina and as an adult by Anna Paquin), the daughter who will become her father’s judge.)

Zaillian domesticates Mob patter with gouts of Tarantino-esque dialogue, inspired by Sheeran’s reminiscences – about chain-smoking wives, the right dress code for meetings, and what type of fish Chuckie O’Brien delivered to a friend in the car he drove to collect his foster father Hoffa for the hit (which he may not have known about). These conversations cost the film some gravitas.

The overarching irony of The Irishman – tonally close to 1990’s Goodfellas – is that it is knowingly based on what may be a cynical if self-shaming fantasy, concocted by Sheeran in his interviews with Brandt to profit his heirs posthumously; Jordan Belfort’s orgiastic The Wolf of Wall Street memoir is similarly suspect. There is no documentary evidence that Sheeran, a known drunk, shot Hoffa, Joe Gallo, or Salvatore ‘Sally Bugs’ Briguglio, or was responsible for any of the numerous hits he claimed. His meticulous description of Hoffa’s killing does suggest that he was present and had conspired in it, but Briguglio, hitman for Teamsters official ‘Tony Pro’ Provenzano, was also there and had the greater motive.

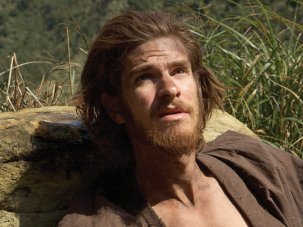

If Sheeran did, in fact, shoot Hoffa, it would indicate that the carnage he participated in as an infantryman in Europe in World War II numbed him psychologically. Scorsese, who shows Sheeran executing two German soldiers, said at a New York Film Festival press conference that Sheeran wasn’t “psychotic” (meaning psychopathic), which deepens the mystery of how he could have carried out the hit, unless the comply-or-die ultimatum issued to Hoffa – “It is what it is” – applied to him too.

The Irishman features bravura dolly and travelling shots and the use of intertitles humorously describing how various mobsters met their ends. But it is less stylised than most Scorsese films, and Robbie Robertson’s score is subdued, a few period pop songs aside. The mastery here is in Scorsese and editor Thelma Schoonmaker’s orchestration of Mob depredations, Hoffa’s rousing of the rank and file (in scenes packed with everyday physiognomies worthy of Elia Kazan) and the intimate talks between Sheeran, Bufalino and Hoffa, with Pesci’s quiet and subtle performance, a thing of beauty, balancing Pacino’s bellicose but charming one.

Sheeran’s journey is richly contextualised by the era’s political shakeups: John F. Kennedy’s election, the Bay of Pigs fiasco, the Cuban missile crisis, Robert Kennedy’s hunting of Hoffa, JFK’s assassination (which lights up Hoffa’s eyes – Pacino’s best moment) and Watergate. It’s hard to believe that Sheeran delivered arms to the CIA’s Howard Hunt in Florida and had a conversation about Hunt’s ears, or played a role in the 1963 cataclysm coded ‘Dallas’, but Scorsese knows that ‘printing the legend’ tells its own truths.

-

Sight & Sound: the November 2019 issue

Martin Scorsese on Robert De Niro and The Irishman. Plus Joaquin Phoenix, Monos and Maurice Pialat’s New French Realism.

-

The 100 Greatest Films of All Time 2012

In our biggest ever film critics’ poll, the list of best movies ever made has a new top film, ending the 50-year reign of Citizen Kane.

Wednesday 1 August 2012

-

The best films now on UK streaming services

Looking for the best new cinema releases available on British VOD platforms? Here’s our guide to how to keep up with the latest movies while you’re...

-

BFI London Film Festival 2019 – all our coverage

We’ve reviewed over 50 (and rising) of the films programmed in this October’s London Film Festival. Find them all here.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.