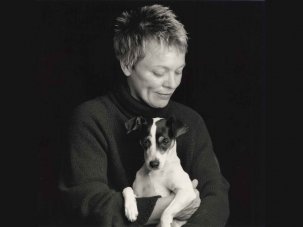

Laurie Anderson’s Heart of a Dog, a sort of first-person monologue delivered by the filmmaker while the viewer bobs along on a surface of flowing images, is a piece of work unmistakably steeped in death. The Tibetan Book of the Dead is cited, particularly in association with the last hours of Anderson’s friend, the artist Gordon Matta-Clark, which she recounts in detail.

USA/France 2015

Certificate PG 76 mins approx

Director Laurie Anderson

In Colour and Black & White

[1.78:1]

UK release date 20 May 2016

Distributor Dogwoof

dogwoof.com/heartofadog

► Trailer

Early on, narrating over 8mm home movies, archival footage of trains and a windshield flecked with snowflakes, Anderson, in a cadence defined by unusual placements of emphasis, twists of phrase and a sense of constant gee-whiz discovery, describes the death of her mother, remembering her slipping into a delirium and “talking to the animals that had gathered on the ceiling”. At the film’s close, Anderson will revisit this scene, which by then takes on a different import. Anderson also describes two near-death childhood experiences and – centre of all this – the 2011 passing of her pet rat terrier Lolabelle, who died at home, having already lost her sight some years before.

At no point in Heart of a Dog does Anderson speak about the one death that you might most expect her to talk about, that of her husband Lou Reed, which occurred slightly less than two years before her film premiered at the Telluride festival, and in the middle of its composition. In a sense, she doesn’t need to. Reed is the film’s structuring absence, never referred to by name but present in Anderson’s every frequent, casual use of the pronoun ‘we’, briefly glimpsed in a bit of home video taken on the beach, and finally providing a coda of sorts when Turning Time Around, a song from his 2000 album Ecstasy, plays over the closing credits, which include a dedication.

A line from Tibetan Buddhist teacher Mingyur Rinpoche that Anderson reads in Heart of a Dog – “You need to try to master the ability to feel sad without actually being sad” – also appeared in a tribute essay to Reed that Anderson published in Rolling Stone magazine. Even if Reed’s name is never spoken aloud, this rumination on death in general can seem to focus on his death in particular, and Heart of a Dog might be the companion to Reed’s own album-length meditation on the final frontier, 1992’s Magic and Loss, released the year that he and Anderson began their lives together.

There is nothing in Heart of a Dog that quite equals the stark, emotionally raw desolation of that album’s Cremation – Ashes to Ashes, but then Anderson is seeking quiet acceptance rather than raging against the dying of the light. Several of the preoccupations that run through her work in theatre and music are present in Heart of a Dog, including the surveillance state and Tibetan Buddhism, but this prolific polymath has no familiar cinematic style that we can refer back to.

Underwritten by the French-German television channel Arte, this is the 69-year-old artist’s first feature since the concert movie Home of the Brave: A Film by Laurie Anderson 30 years ago, and she approaches the form nearly as an amateur. For the most part, the movie comprises a soundtrack consisting of Anderson’s narration and incidental music, predominantly electronic drone and violin phrases that circle like birds of prey, as well as occasional bursts of sung song, all laid over a series of images.

The soundtrack – the full 75 minutes of it, Turning Time Around and all – has also been released as a standalone spoken-word record, a piece of work that no less a personage than the American rock critic Robert Christgau has called Anderson’s “simplest and finest album”. If Anderson regards Heart of a Dog as a complete artwork in its long-player form – and I believe it is – it’s worth exploring what, if anything, the pictorial dimension adds to the sonic.

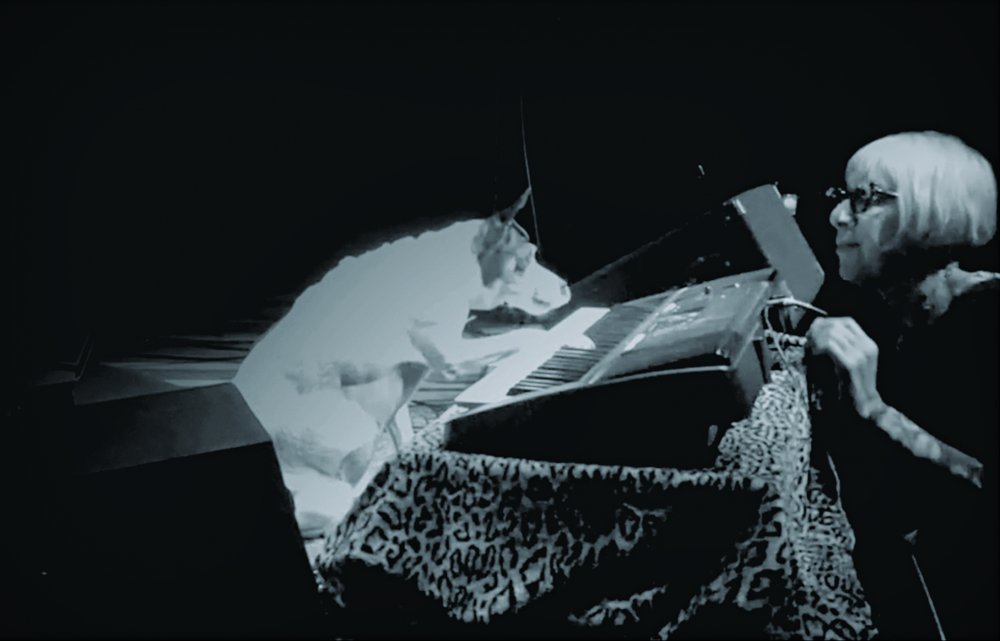

Early on, the relationship between the aural and visual element is quite straightforward, even fairly literal-minded. When Anderson describes her dog learning piano at the behest of a trainer, we see Lolabelle yipping and pawing at a keyboard. When Anderson speaks of the end of Lolabelle’s life, we see deathbed photographs of the pet with her grey muzzle and bloodshot, sightless eyes. After Lolabelle dies, her passage through the bardo – a kind of waiting room described in Tibetan Buddhism, in which the dead await their rebirth – is illustrated by Anderson’s own paintings. When Anderson speaks of Lolabelle’s first owners, a divorced couple, or the veterinarians who advised putting her down in her final illness, or the doctors who told Anderson she wouldn’t walk again after a childhood accident, this material is accompanied by ‘re-enactments’ that are rather close to clip-art generic.

There is an attempt to represent, via GoPro-shot footage, the ankle-level POV of Lolabelle plunging along the streets of the West Village, along with other foreign perspectives, such as those of the surveillance state’s million eyes or the vast catalogue of images, gathered in data-storage facilities like those maintained by Iron Mountain Inc, in which Anderson sees a digital afterlife for all of us. She also summons up analogue ghosts: the 8mm home movies of the Anderson family play out in spectral slow motion, seen through a writhing layer of chemical blotches and scratches that initially give the impression of being flaws on the film itself, though as they persist over transitional blackouts and new footage taken on digital video, it becomes obvious that this is a postproduction effect.

As the film goes along, Anderson begins to abandon the strictly illustrative approach, and her employment of textured, partition-like layering effects increases. Certain images that first appear by themselves – the crack-seamed “huge gold void” of Goya’s The Dog, a pane of glass or a windshield beaded with rain or wet snow, the sky viewed between the overarching bare limbs of trees – reappear, piled atop one another or atop newly introduced images.

As these images recur, Anderson’s narration also loops back, returning to pick up subjects dropped earlier on, when her attention seemed to be diverted elsewhere. These switchbacks in turn lead to the reprisal of musical themes – it should come as no surprise that the film’s overall almost palindromic construction feels like that of a concept album.

Anderson’s narration ends, very nearly as it began, with her recalling her mother’s death, an event she initially finds herself unable to mourn, unlike the passing of Lolabelle. (“We” – there’s that we again – “had learned to love Lola as she loved us, with a tenderness we didn’t know we had.”) Anderson attempts to address this failure through a Buddhist exercise called the ‘Mother Meditation’, which asks in part that one “imagine that you’ve been everyone’s mother, and they’ve been yours”.

This idea connects to the film’s opening, in which Anderson – who appears briefly in this section as a rotoscoped pen-and-ink cartoon – recounts a dream of giving birth to Lolabelle after having the dog stitched into her stomach. Anderson’s explanation of the Mother Meditation is followed immediately by a reprise of the same tune, The Lake, that accompanied the recounting of the dream, this time in a version with vocals.

All of which is to say that the apparently free-associative peregrinations of Anderson’s voiceover are anything but random, and as she weaves together anecdote, autobiography, current events and demotic philosophy, the same themes recur in new guises: love, loss, memory, sorrow, survival and the complexities of telling the really real way that a thing happened. As Heart of the Dog plays through, its junky, rinky-tink imagery acquires a sense of greater depth and weight, even elegance – the expression of a story that discovers itself in the telling.

-

Sight & Sound: the June 2016 issue

Whit Stillman on his acid-tongued Jane Austen adaptation Love & Friendship. Plus Richard Linklater’s college daze, Lucile Hadzihalilovic&...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.