Spoiler alert: this review discusses the ending of the film

The Algiers Motel incident, wrote John Hersey in his book of that title, “contained all the mythic themes of racial strife in the United States”. It took place at the height of the Detroit riots of July 1967, while blocks of the city were on fire, but at a remove from the rioting. Indeed, Dramatics singer Larry Reed, as close to a protagonist as Kathryn Bigelow’s film has, and his friend Fred Temple, one of three young black men shot dead by Detroit police at the motel that night, had gone there to get away from the violence after their gig at the Fox Theatre downtown, on the same bill as Martha and the Vandellas, was cancelled. Like Bigelow’s Zero Dark Thirty (2012), Detroit is a selective dramatisation and bound to be controversial, as any such dramatisation would be, but it is vivid and compelling, encompassing all the themes Hersey identified without treating the incident as merely illustrative.

USA 2017

Certificate 15 142m 48s

Director Kathryn Bigelow

Cast

Melvin Dismukes John Boyega

Krauss Will Poulter

Larry Reed Algee Smith

Fred Temple Jacob Latimore

Carl Cooper Jason Mitchell

Murray Julie Hannah

Dever Karen Kaitlyn

Demens Jack Reynor

Flynn Ben O’Toole

Auerbach, attorney John Krasinski

Greene Anthony Mackie

[1.85:1]

UK release date 25 August 2017

Distributor E1 Films

detroitmovie.co.uk

► Trailer

After a brief animated sequence filling in some of the background – most relevantly, the city’s de facto residential segregation – the film begins with a heavy-handed police raid on a coming-home party for a black Vietnam veteran. The main characters emerge only gradually out of a mosaic of short scenes, all of which combine to give a sense of the extent of the rioting but also of its limits.

The soul revue at the Fox Theatre appears as an oasis, a glimpse of the version of Detroit that Motown had presented to the world in the mid-1960s. Larry (Algee Smith) is first seen practising with his bandmates backstage while the Vandellas, seen from behind, perform Nowhere to Run to a racially mixed audience: The Dramatics are on the brink of success in this world, at the very moment when the curtain is pulled down on it. Even as their bus travels north through the riots, Larry’s bandmates are more keen than he to get involved, and once at the Algiers, Larry and Fred (Jacob Latimore) concentrate on getting laid.

Anthony Mackie as Greene

But it is this that, indirectly, seals their fate. The police come to the motel after shots are fired from the annexe Larry and Fred are staying in, and the presence of two young white women among black men is a significant factor in the ordeal that follows. A large proportion of the movie – about 45 minutes – is given over to the ‘incident’ itself, in which all the annexe’s occupants are beaten and abused, in addition to the three killed.

The weight in this sequence shifts on to John Boyega’s character, Melvin Dismukes, a black security guard who is placed in an agonisingly ambiguous position: tolerated by the white policemen as an armed man in uniform, but only barely, and never securely enough placed to rein them in. What might be most characteristic of Bigelow is the eerie feeling that the police are halfway ‘acting out’, performing their brutality; another bystander, Roberts (Austin Hébert), a white National Guardsman, might end the torment with a word, but doesn’t.

Melvin ends the film in a bitter double bind, tried and exonerated alongside the white cops who still look at him with scarcely concealed contempt. The Dramatics, meanwhile, land a record deal, but Larry renounces fame, unwilling to dress up like the Four Tops to entertain a white audience as if nothing has happened. Though he quits without acrimony, what looked like an oasis proves just a mirage. He becomes director of a church choir. Smith is one of the less well-known actors in Bigelow’s ensemble, but gives the standout performance, particularly in these later scenes.

I found the ending of Detroit a little unsatisfying, at least on the basis of a single viewing. Perhaps it ought to be: justice was not done, “racial strife in the United States” hasn’t gone away, and the bitterness and lack of resolution are appropriate.

However, the film’s momentum is dissipated in the shift from what might well be real time during the Algiers Motel scenes to what amounts to a montage sequence covering the aftermath, but missing out some crucial links in the chain. The trial is not brought to life, as the earlier scenes are, but sketched, and Bigelow loses the focus on character that is the strength of the body of the film, without expanding its scope to take in the incident’s political repercussions. But in a sense this disappointment is testament to how rich the characterisations are, and how powerful her film is.

In the September 2017 issue of Sight & Sound

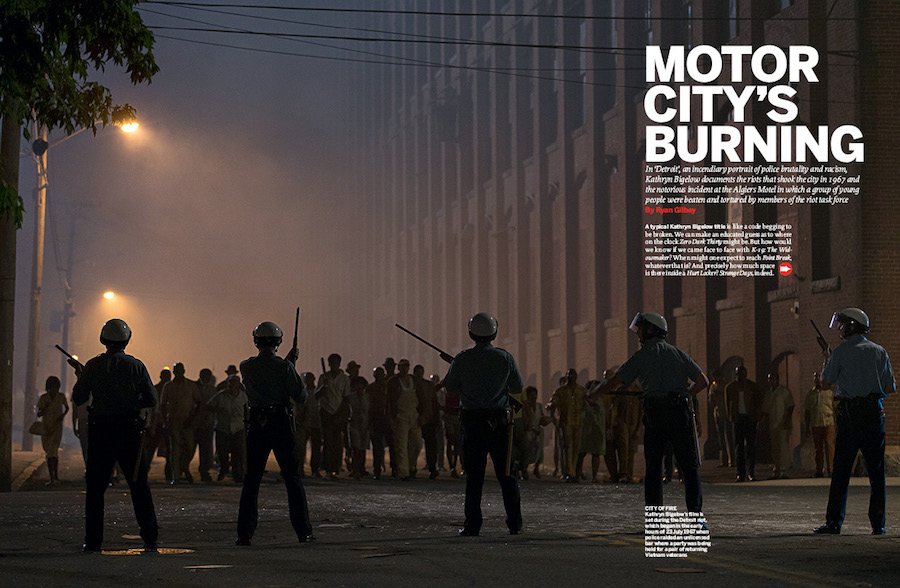

Motor City’s burning

In Detroit, an incendiary portrait of police brutality and racism, Kathryn Bigelow documents the riots that shook the city in 1967 and the notorious incident at the Algiers Motel in which a group of young people were beaten and tortured by members of the riot task force. By Ryan Gilbey.

-

Sight & Sound: the September 2017 issue

Kathryn Bigelow on John Boyega and Detroit, plus A Ghost Story, God’s Own Country, Jean-Pierre Melville and Cuban documentary filmmaking.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.