Spoiler alert: this review reveals narrative details

You might read it primarily as a portrait of one ordinary family’s ups and downs, in which race is but a single factor; or as an urgent, rather angry statement about negative aspects of current African-American life. Either way, Jonathan Olshefski’s documentary is certainly an eloquent argument in favour of the kind of filmmaking that takes ‘ordinary’ people, rather than PR-savvy celebrities or obviously world-shaking events, as its subject matter. Simply by observing, with interest, respect and infinite patience, the quotidian lives of its highly likeable protagonist and his family, the film attains a rare level of insight and complexity. And while there are emotional extremes and instances of high drama, quieter moments are just as likely to linger in the viewer’s mind.

USA 2017

Certificate 12A 104m 3s

Director Jonathan Olshefski

[1.78:1]

UK release date 18 August 2017

Distributor Dogwoof

dogwoof.com/quest

► Trailer

Olshefski, a tutor in photography, was initially introduced to Christopher ‘Quest’ Rainey by Rainey’s brother, who was one of his students. A photo essay was the initial plan; gradually, though, Olshefski determined that cinema was a better medium in which to convey what he was observing.

Not that a grand plot was evident; rather, the Raineys appealed because of the magnetism of their personalities, and the way their exuberantly populous household in North Philadelphia served as an unofficial community hub. The director went on to film them through the bulk of Barack Obama’s presidency (which is referenced, the Raineys being enthusiastic supporters) and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement (which isn’t directly mentioned but does become painfully relevant).

Quest’s partner, Christine’a, known to the community as Ma Quest, becomes his wife at the start of the film, after 15 years together. The relationship, Quest tells the camera, is akin to that of a left and a right hand. Though radically different, they unceasingly complement and aid one another. Both have survived troubled upbringings, of which we learn a little – he dabbled in selling crack, she was horribly burned in a domestic accident – but what seems to unite them more is their intelligence, patience and good humour in the face of challenges. Their fidelity and mutual respect are taken as read, without being overplayed or sentimentalised. At one point, Christine’a punctuates a slightly grouchy marital dispute with the firm reminder: “I love you with all of my heart.”

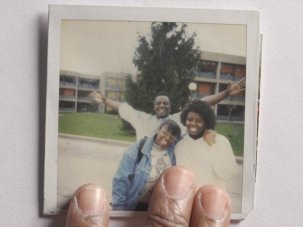

Music producer Christopher ‘Quest’ Rainey and his wife Christine’a

That their unquestioning faith in one another reads as surprising, even exotic, is sobering testament to the extent to which longstanding marriages tend to be portrayed in popular culture as sites of discontent, boredom and secrecy. Here, the simple act of being and staying in love provides not only an enviable and inspiring example of solidarity for the audience, but also a gentle rebuke to the stereotype of black men as cheaters and abusers, and black women as victims and survivors. Lemonade – the metaphor deployed by Beyoncé Knowles on her 2016 ‘visual album’ for the sweetness that can be sourced from female suffering – is certainly made here, but it’s made by both Raineys, together, with humour and hope as well as sorrow and stoicism.

Beyoncé crops up elsewhere, as a symbol of another of the film’s underlying concerns: the enlistment of distant, fabulously wealthy superstars as aspirational figures for young people, rather than solid contributors to their own communities. “How did Meek Mill and Jay-Z become our leaders?” demands a speaker at a small local protest against the gun violence escalating all around. “Where they at now? Where are Beyoncé and Rihanna now? Our first role models should be us.”

Such is the role that Quest and Christine’a have forged or had thrust upon them: she works in a shelter for women and children; he supports the artists he records and produces when they repeatedly run into difficulties with money or substances; and both are active in encouraging the local community to engage in politics and to register to vote. At one point, a radio DJ on whose programme Quest often appears tells him that the couple deserve to have their relationship recognised with some sort of award.

Christopher Rainey, his grandson Isaiah, his wife Christine’a and his daughter PJ

Tragically, the specific issue of gun violence acquires a significance far greater than the political to the Raineys when their daughter PJ is badly injured by a stray bullet fired in a street fight and loses an eye. That this incident occurs in the midst of the film being made is startling and awful: as viewers, we are just getting to know these people, revelling in their warmth and vigour, when utterly unearned ill fortune shatters all certainties. If it’s in the interests of a self-righteous and viciously judgemental right wing to characterise all gun violence in black communities as self-inflicted – “Dear black people. If your lives matter why do you stab and shoot each other so much?” tweeted the British columnist Katie Hopkins earlier this year – PJ’s experience is a reminder that when guns are part of daily existence and their deployment a feature of petty disputes, even the purest innocence is no defence against getting caught in the crossfire.

That the family permitted Olshefski to keep filming through this terrible time shows their bravery and confidence, and secures for the world an extraordinary account of the behind-the-scenes reality of such a trauma. PJ’s complex response to her slow recovery is profoundly moving to behold. When she is fitted with a glass eye, relief and gratitude do visible battle with her ongoing fury and horror at being handed this undeserved life sentence. Humour even enters the mix. When a local eccentric lectures PJ at length, saying she’s still beautiful and God still loves her, PJ complainsto Ma Quest, who defends the woman. PJ, likely echoing the feelings of most viewers, prefers her own simple diagnosis: “She crazy.”

The lengthy filming span permits us the pleasure of seeing PJ regain much of her swagger and confidence. Before too long, her eye has taken second place in her parents’ concerns to the revelation that she’s gay. This is a test of the Raineys’ own much vaunted liberalism: discussing the matter, they profess theoretical support for PJ, but can’t resist assigning blame to one another for the direction she’s taken. “There’s so many levels of being gay now,” complains Quest. “I used to think either you’re gay or you’re not…” “L, G, B, T…” says his wife. “What’s the other two? I forget.”

PJ, meanwhile, blossoms; and pretty soon the cost of her clothing is more of an issue than who it’s meant to impress. “Oprah Winfrey is not here to give you the wardrobe that you need,” her mother tells her – emphasising once again the effect on the lives of young people of role models whose wealth and achievements are beyond the range of realistic aspiration.

Meanwhile William, another of Ma Quest’s children, copes with his own share of lemons: an unstable relationship, a new baby and a brain tumour that presses on his pituitary gland. “He’s not ready to be a father yet,” Ma Quest says, willingly taking on her share of the childcare even though she still has her own dependent children to support. Down the line, however, fatherhood proves to be a help to William’s slow recovery; his toddler is “always playful”, keeping his father’s spirits up as he shakes off the last of his symptoms and side effects.

This is loving, humane, substantial stuff, with the richness of a fat novel rather than the sensationalism and cruelty of reality TV. The subtlety with which Olshefski has observed his subjects and disappeared himself is breathtaking; no less worthy of praise is the work of editor Lindsay Utz in condensing some 300 hours of footage into an eventful and utterly absorbing 105 minutes.

In one of the film’s more on-the-nose moments – but a highly effective one – we see the Raineys watching a campaign speech by future president Donald Trump. “It’s a disaster the way African Americans are living,” he declares. “You don’t know how we’re living,” Christine’a snaps back at her TV. Few could query her indignation: if misfortune has certainly befallen this family, the idea that their vibrant, busy and loving lives constitute some distant and anonymous state of perpetual “disaster” is as preposterous as it is patronising.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.