Alongside a packed programme of more than 400 films about the presence of feelings at the 2019 International Film Festival Rotterdam, Dutch critics Dana Linssen and Jan Pieter Ekker produced Critics’ Choice V: Absence. Prodding the philosophical ways that film might be thought about as an object or artefact, and how the criticism that surrounds it might be a form of memory itself, Linssen and Ekker invited ten international film critics to create video essays and performances in response.

Re-enacting the Future premiered at the 2019 International Film Festival Rotterdam, and is on on Vimeo.

See more of Kevin B. Lee’s work at alsolikelife.com and Galibert-Laîné’s at chloegalibertlaine.com.

Responding to Radu Jude’s smart and acerbic I Do Not Care If We Go Down in History as Barbarians, Kevin B. Lee and Chloe Galibert-Laîné offered up a potent premonition of film inciting revolt with their video essay Re-enacting the Future. It begins with a short clip from Shooting Captured Insurgents (1898). Four Spanish soldiers each march a Cuban rebel to a wall, step back and shoot. The words on screen tell us, “It is the first mass execution captured on film.”

For a second or two, I wonder if the footage and therefore the execution might be real. There are instances captured on film that are supposedly so, namely Luis del Castillo’s El Bolillo Fatal o el Emblema de la Muerte (The Fatal Lottery or the Emblem of Death, 1927) – although it was censored almost immediately on release and remained unseen for another 85 years, until history deemed its presence worthy enough to be remembered, despite its morbid content. Thankfully, the next intertitle allays my concern: “It is also one of the first staged re-enactments in film history.”

Shooting Captured Insurgents (1898)

Film is still in its infancy in 1898 and its exhibitors, who hope to attract audiences with its novelty, find that even new technology has its limits: the presence of any image is loaded with the absence of its referent (a notion the likes of Walter Benjamin and Roland Barthes will better theorise as the years wear on). It will be almost 20 years before The Battle of the Somme (1916) shows the world what ‘documentary’ and ‘propaganda’ are all about; and another six after that before Nanook of the North (1922) further complicates our understanding of what showing and presenting really mean. In 1898, these concepts, it seems, are up for grabs.

The Battle of the Somme (1916)

Lee and Galibert-Laîné then repeat the image but, this time, it takes up more space – literally. Keeping its 1.37:1 frame, the almost-square image sits now a little more comfortably in the centre of a contemporary CinemaScope cinema screen. Though there is still plenty of black – signally the absence of a full or complete view – the image is now insistent. The intertitles reveal that the sequence was filmed during the Spanish-American war at Edison Studios, based on journalism from the front lines, with American soldiers playing all parts. The clip then screens for a third time, enlarged once again, taking up as much screen space as it can, allowing for the limitations of its historical aspect ratio as it clashes with our contemporary gauge.

Watching the images for a third time, I am struck with a sense of unease. It isn’t until the term ‘nationalist fervor’ appears, however, that a painful resonance sets in: this is not just film criticism as an act of memory; it is an exercise in feeling historical and contemporary modes of mediated nationalism on the rise.

The war, for all of its filmic glory, then, is given credit for revitalising an already flailing marketable art form. “Films were three years old and losing their novelty appeal,” the intertitles explain. I roll the word novelty around in my mouth for days to come, like a hard-boiled sweet, occasionally gritting my front teeth, to stop from spitting it out. The idea of a novelty should be linked to innovation and curiosity in our minds, but today it holds a far more negative connotation. The ‘novelty’ of film has always been both its curse and its saving grace; audiences are fickle and once they work out how the trick is done, they want another, not just new but improved. Did it really only take three years of moving images before audiences hungered for killing as entertainment?

Lee and Galibert-Laîné wonder, too, about the role of re-enactment in entertainment, and resolve that “They enact a future where new image industries convert violent fantasy into political power.” Though it seems impossible, the image is made bigger still on the screen before me. It is hideously blurred now, so that I can only see a part of the picture and am forced to contemplate the reality or truth of the thing.

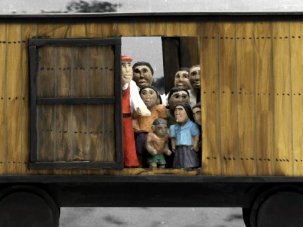

La Commune (2000)

After this crash course in pondering early cinema and its impact on our political psyche, Lee and Galibert-Laîné move onto their next subject, Peter Watkins’ La Commune (2000), often credited as the greatest cinematic re-enactment ever made. The intertitles that silence afforded us just moments ago are now replaced with a scrolling text banner across the bottom of the screen, as if this were a 24-hour news broadcast, where I am invited to do the impossible: to read, watch and listen all at once.

Lee and Galibert-Laîné explain how Watkins hacked the codes of television news, which “freed the past from the conventions of historical filmmaking, bringing it alive in the present”. But they are also hackers: of silent film, of Watkins’ film and of our contemporary codes of understanding truth in narrative.

At this moment I start to wonder if I ought to read the scrolling text as authorial intent, because isn’t that what the format asks of me? Can I be critical of criticism? With our eyes flickering between text and image, there is no time to reflect – another nod to the contemporary news cycle, the endless echo chamber that is cyberspace and the time economy of IRL (in real life) that needs to forget. If criticism is a form of memory, then surely forgetting is a form of fascism?

The non-professional actors Watkins chose for La Commune were selected for their sympathetic views to the characters they play. The performance is not acting, it is authenticity in motion. As Lee and Galibert-Laîné ask what the final execution scene of La Commune was really a rehearsal of, they also move seamlessly from the faces and voices of children in 2000 representing 1871 to present-day iPhone footage of the Gilets Jaunes. Both chant rather than sing La Marseillaise. Screens from YouTube, Facebook and C News fill the screen, complete with scrolling text banners. The edit is smooth but throws the viewer into cinematic chaos, a critical provocation to challenge a perception of the novelty of cinema.

Now primed to question the motivations of re-enactment for audience entertainment as well as its ability to replace the critical utility of memory – especially resonant in a collective setting such as a cinema auditorium – I exhale, and Radu Jude’s I Do Not Care If We Go Down in History as Barbarians begins.

I Do Not Care if We Go Down in History as Barbarians (Îmi este indiferent dacă în istorie vom intra ca barbari, 2018)

One of the most critically, theoretically, philosophically and literarily dense films I’ve ever seen, Barbarians is a meta-meta narrative in which an actress introduces herself and the role she will play. Pretending to be a theatrical director, she will stage a public re-enactment of Romania’s involvement in the 1941 Odessa massacre. The film’s intention is to reveal the polemic involved in re-examining and challenging the propaganda of collective memory of historical events. But Radu Jude’s thesis is also his challenge, and one that reflects the wider concerns of IFFR’s Critics Choice V: Absence programme. The resulting question is what to do with critical thought when it is not only an act of memory, but a competing act of memory, up against nationalism, poetic licence, persecution, fear and power.

Joining Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing (2012), Rithy Panh’s The Missing Picture (2013) and Lola Arias’s more recent Theatre of War (2018), Barbarians sees the problem of history as an urgent and persistent concern. Primarily interested in challenging the narrative, Jude’s attempt is to intercept collective, public memory precisely at the point in which fear and power enact social and political amnesia, annihilating critical thought.

Lee and Galibert-Laîné are, with Re-enacting the Future, also trying to stage an intervention. They hope that in staging this critical act, they will create a memory that stops forgetting from setting in. It is a sort of Heideggerian nothingness that Lee, Galibert-Laîné, Jude, Linssen and Ekker are all afraid of, perhaps best understood as in a children’s fable, as the terrifying entity from Wolfgang Petersen’s enlivened classic The Neverending Story (1984). If we don’t remember histories, and critically engage, then the nothingness will envelop it all.

—

Correction (18 March 2019): the word ‘re-enactment’ was changed to ‘rehearsal’ in the final paragraph about La Commune.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.