Web exclusive

Revised and expanded, 25 October 2013.

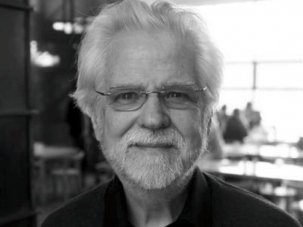

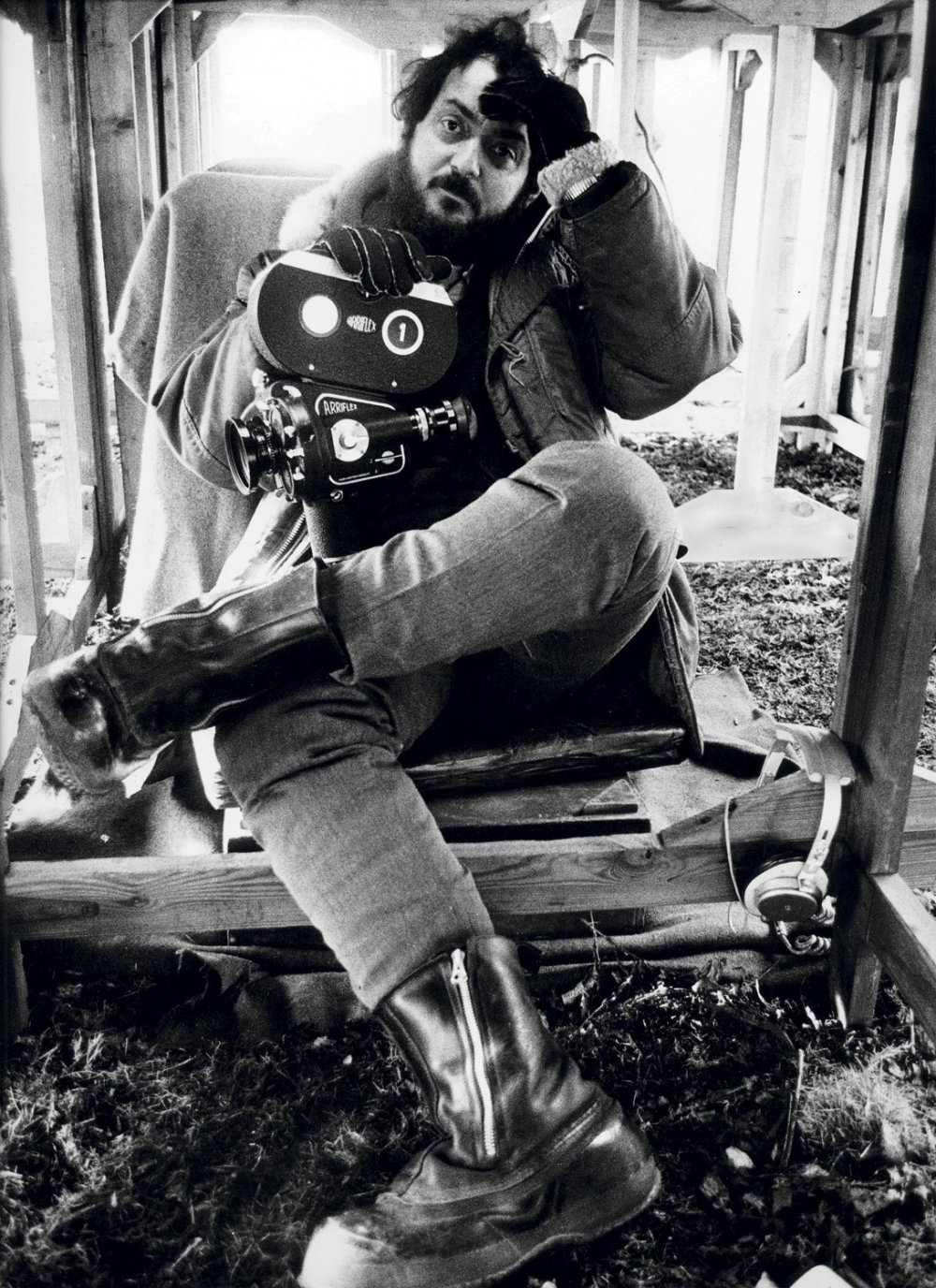

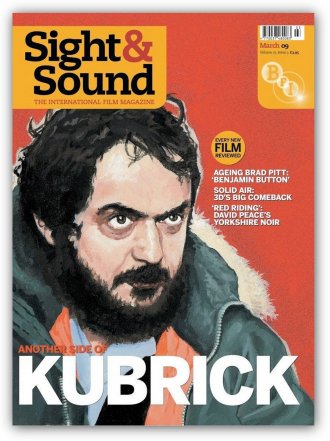

Stanley Kubrick, photographed by Dmitri Kasterine in 1970 on the set of A Clockwork Orange.

Credit: Dmitri Kasterine: www.kasterine.com

Stanley Kubrick worked for almost half a century in the medium of film, making his first short documentary in 1951 and his last feature in 1999. He went to extraordinary lengths to avoid mediocrity in his work, in order that it might last and not fall into oblivion. With each project, his initial preoccupation involved trying to find the right story. Some arrived quickly – Terry Southern handed Kubrick a copy of Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange in the 1960s and Kubrick persuaded Warners to buy the rights immediately – but later projects came more slowly or were regretfully abandoned after years of research due to events out of his control. However, once a story was settled on, Kubrick strove to make a film unlike any other before it.

Seventeen years after Kubrick’s sudden passing, the intensity of his exacting filmmaking methods seems to be mirrored by the enthusiasm of his admirers to learn everything about him. Every aspect of his films continue to be pored over endlessly. In the late 1990s when he was making his last film, Sight & Sound suggested there were “few directors still working [who are] so fascinating to our readers” [S&S, September 1999].

I count myself among the many admirers of Kubrick’s films and his remarkable aptitude for problem solving in all areas of life. I would argue that the only remaining unexplored area of Stanley’s life in film is his relationship with, and love of, other people’s films. In his later life he chose not to talk publicly about such things, giving only a couple of interviews to large publications when each new film was ready – but through his associates, friends, and fellow filmmakers it’s now possible to piece together a revealing jigsaw.

I wanted to try and pull together all the verified information I could locate and have it looked over by a wise, authoritative eye. I was delighted to find Jan Harlan, Kubrick’s confidant, relieved to talk about something other than the director’s own films (there’s only so many times a man can be asked about the ending of 2001: A Space Odyssey), so I set out to try and dislodge some recollections from his memory bank. Read the interview here.

If you don’t find it interesting that David Lynch counts Rear Window and Sunset Blvd. among his favourite films, that Woody Allen doesn’t find Some Like It Hot at all funny, or that Kubrick loved all these filmmakers, the following is probably not going to be of much interest.

Why does it matter what Kubrick liked? For years I’ve enjoyed unearthing as much information as I can about his favourite films and it slowly became a personal hobby. Partly because each time I came across such a film (usually from a newly disclosed anecdote – thanks internet! – or Taschen’s incredible The Stanley Kubrick Archives book) I could use it as a prism to reveal more about his sensibilities. My appreciation of both him and the films he liked grew. These discoveries led me on a fascinating trail, as I peppered them throughout the 11 existing Kubrick features (not counting the two he disowned) I try to watch every couple of years. I’m sure a decent film festival could be themed around the Master List at the end of this article…

Early days

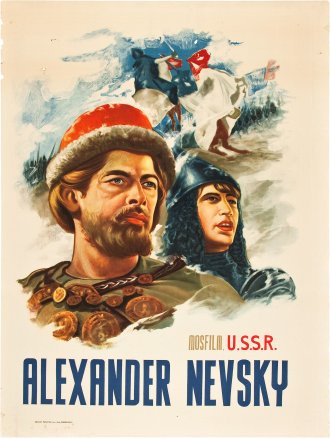

Young Kubrick, in addition to his other great love at the time – chess, which he played daily – “assiduously attended screenings at the Museum of Modern Art”, in the words of Michel Ciment. Here he saw the great films of the silent era, amongst others. His high-school friend and early collaborator Alex Singer particularly remembers them both going to see Alexander Nevsky (1938) – because immediately afterwards Kubrick bought an LP of the Prokofiev score and played it continuously, until he drove his younger sister so crazy she smashed the LP on his head.

In 1987, Kubrick touched on this period of his life in a newspaper interview:

“My sort of fantasy image of movies was created in the Museum of Modern Art, when I looked at Stroheim and D.W. Griffith and Eisenstein. I was starstruck by these fantastic movies. I was never starstruck in the sense of saying, ‘Gee, I’m going to go to Hollywood and make $5,000 a week and live in a great place and have a sports car’. I really was in love with movies. I used to see everything at the RKO in Loew’s circuit, but I remember thinking at the time that I didn’t know anything about movies, but I’d seen so many movies that were bad, I thought, ‘Even though I don’t know anything, I can’t believe I can’t make a movie at least as good as this’. And that’s why I started, why I tried.”

— Interviewed by Lloyd Grove, Washington Post, June 28th 1987

The first and only (as far as we know) Top 10 list Kubrick submitted to anyone was in 1963 to a fledgling American magazine named Cinema (which had been founded the previous year and ceased publication in 1976). Here’s that list:

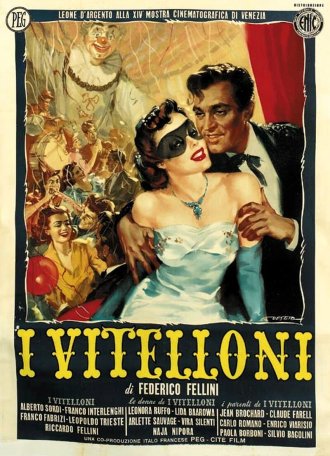

1. I Vitelloni (Fellini, 1953)

2. Wild Strawberries (Bergman, 1957)

3. Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941)

4. The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (Huston, 1948)

5. City Lights (Chaplin, 1931)

6. Henry V (Olivier, 1944)

7. La notte (Antonioni, 1961)

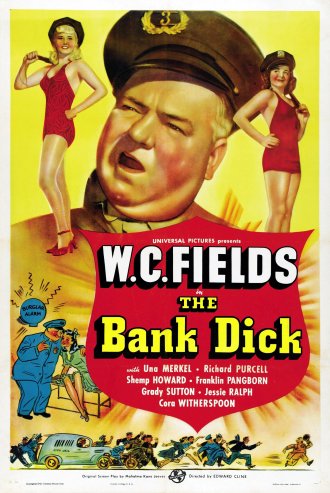

8. The Bank Dick (Fields, 1940)

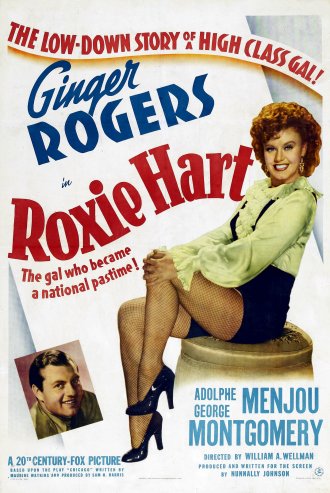

9. Roxie Hart (Wellman, 1942)

10. Hell’s Angels (Hughes, 1930)

As Harlan told me: “Stanley would have seriously revised this 1963 list in later years, though Wild Strawberries, Citizen Kane and City Lights would remain, but he liked Kenneth Branagh’s Henry V much better than the old and old-fashioned Olivier version.” (It’s interesting to note just how many formidable filmmakers have included City Lights in their lists of favourite films: Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Milos Forman, Kubrick, David Lean, Carol Reed, Andrei Tarkovsky, King Vidor, and Orson Welles all have.)

Michel Ciment has pointed out that Max Ophuls and Elia Kazan are notably absent from Kubrick’s 1963 Top 10. In an early interview with Cahiers du cinéma in 1957, Kubrick said:

“Highest of all I would rate Max Ophuls, who for me possessed every possible quality. He has an exceptional flair for sniffing out good subjects, and he got the most out of them. He was also a marvellous director of actors.”

Also in 1957, Kubrick considered Kazan:

“…without question the best director we have in America. And he’s capable of performing miracles with the actors he uses.”

In the 1960s, Kubrick said:

“I believe Bergman, De Sica and Fellini are the only three filmmakers in the world who are not just artistic opportunists. By this I mean they don’t just sit and wait for a good story to come along and then make it. They have a point of view which is expressed over and over and over again in their films, and they themselves write or have original material written for them.”

Another rare comment, this time from 1966:

“There are very few directors, about whom you’d say you automatically have to see everything they do. I’d put Fellini, Bergman and David Lean at the head of my first list, and Truffaut at the head of the next level.”

Kubrick rarely discussed in public his thoughts on other filmmakers, so the few times he did are worth repeating. On Chaplin:

“If something is really happening on the screen, it isn’t crucial how it’s shot. Chaplin had such a simple cinematic style that it was almost like I Love Lucy, but you were always hypnotised by what was going on, unaware of the essentially non-cinematic style. He frequently used cheap sets, routine lighting and so forth, but he made great films. His films will probably last longer than anyone else’s.”

On Abel Gance’s Napoleon (1927):

“I know that the film is a masterpiece of cinematic invention and it brought cinematic innovations to the screen which are still being called innovations whenever someone is bold enough to try them again. But on the other hand, as a film about Napoleon, I have to say I’ve always been disappointed in it.”

On two actors he admired:

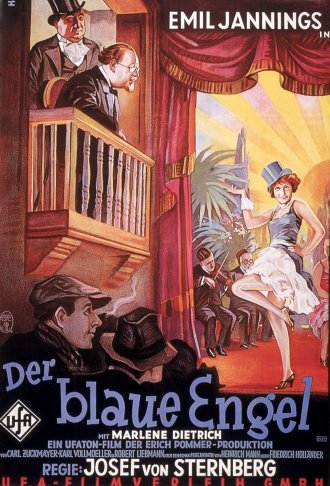

The Blue Angel (1930)

“When you think of the greatest moments of film, I think you are almost always involved with images rather than scenes, and certainly never dialogue. The thing a film does best is to use pictures with music and I think these are the moments you remember. Another thing is the way an actor did something: the way Emil Jannings took out his handkerchief and blew his nose in The Blue Angel, or those marvellous slow turns that Nikolay Cherkasov did in Ivan the Terrible.”

— all from an interview with Philip Strick and Penelope Houston in Sight & Sound, Spring 1972

And on unexpected inspiration:

“Some of the most spectacular examples of film art are in the best TV commercials.”

— Kubrick, Rolling Stone, 1987

The only other authoritative list of films Kubrick admired appeared in September 1999 on the alt.movies.kubrick Usenet newsgroup courtesy of his daughter Katharina Kubrick-Hobbs, introduced with her premonitory words:

“There does seem to be a weird desire from people to ‘list’ things. The best, the worst, greatest, most boring, etc. etc… Don’t go analysing yourself to death over this half-remembered list. He liked movies on their own terms… For the record, I happen to know that he liked:

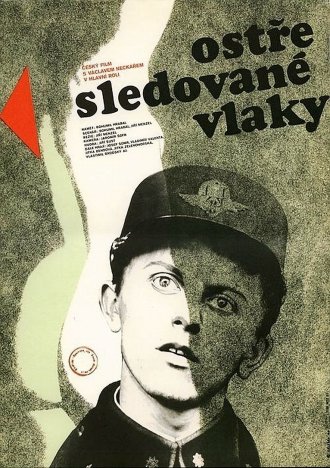

- Closely Observed Trains (Menzel, 1966)

- An American Werewolf in London (Landis, 1981)

- The Fireman’s Ball (Forman, 1967)

- Metropolis (Lang, 1927)

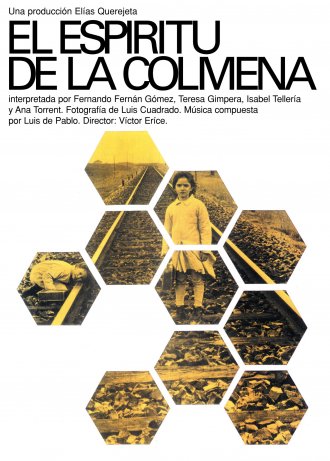

- The Spirit of the Beehive (Erice, 1973)

- White Men Can’t Jump (Shelton, 1992)

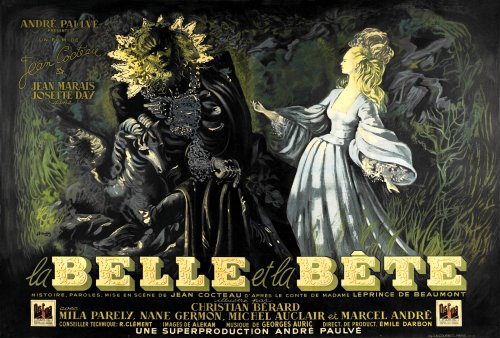

- La Belle et la Bête (Cocteau, 1946)

- The Godfather (Coppola, 1972)

- The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Hooper, 1974)

- Dog Day Afternoon (Lumet, 1975)

- One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest (Forman, 1975)

- Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941)

- Abigail’s Party (Leigh, 1977)

- The Silence of the Lambs (Demme, 1991)

and I know that he hated The Wizard of Oz. Ha Ha!”

In late 2012, a user-generated list appeared at the website of the esteemed American Blu-ray and DVD label The Criterion Collection and promptly shot around the internet, eventually forming the basis of a number of poorly written articles wrongly believing that Criterion themselves had compiled the list. The list in question, compiled by Criterion fan Joshua Warren, combined the two above lists of Stanley’s favourite films that are known to exist (the 1963 Cinema Top 10 and Katharina’s list), along with a smattering of other interesting titles – but the main list only contained titles that had been released by Criterion on disc.

The purpose of this article is to attempt to compile an exhaustive chronological Master List of every film Kubrick is known to have expressed admiration for in some way. Hopefully this will lead to even more stories coming to light. I aim to keep it up to date.

The Master List, 1921-1998

“Stanley was generally very disappointed with commercial cinema… that it could have been so much more… budgets that were squandered on silly stories.”

— Anthony Frewin, assistant to Kubrick (1965-69 and 1979-99), in 2012

The Phantom Carriage

Victor Sjöström, 1921

Metropolis

Fritz Lang, 1927

Frewin: “We spoke about this whilst working on 2001: A Space Odyssey. Stanley thought it was ‘silly’ and even ‘childish’ and couldn’t quite understand why it was held in such high regard.”[Nevertheless, it appeared on Katharina Kubrick-Hobbs’ list of films her father liked.]

Hell’s Angels

Howard Hughes, 1930

Harlan: “I realise it’s on this 1963 list, but strangely, he never mentioned Hell’s Angels to me when we played the forever changing Desert Island Discs game with films.”

The Blue Angel

Josef von Sternberg, 1930

Harlan: “A must.”

City Lights

Charles Chaplin, 1931

The Bank Dick

W.C. Fields, 1940

Citizen Kane

Orson Welles, 1941

Roxie Hart

William Wellman, 1942

Henry V

Laurence Olivier, 1944

Les Enfants du Paradis

Marcel Carné, 1945

La Belle et la Bête

Jean Cocteau, 1946

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

John Huston, 1947

La Kermesse Héroïque

Jacques Feyder, 1935

Kubrick mentioned enjoying seeing it at MoMA and referred to it as “a very nice film” in an interview with Renaud Walter in Positif, issues 100 and 101, December 1968 and January 1969.

Pacific 231

Jean Mitry, 1949

Frewin: “Stanley said Pacific 231 was one of the most perfectly edited, if not the most perfectly edited films, he had ever seen. Not only that but also the way Mitry melded the cutting with Honegger’s music. He thought it was a knockout.

“I’d seen the film just before going to work for Stanley and was always going on about it. He wanted to see it and I borrowed a 16mm print from the BFI.”

Rashomon

Akira Kurosawa, 1950

See the entry for Seven Samurai (1954).

La Ronde / Le Plaisir / Madame de…

Max Ophuls, 1950 / 51 / 53

Harlan: “La Ronde, yes – he was a real Arthur Schnitzler fan. Madame de… with Danielle Darrieux – Stanley loved it.”

Miss Julie

Alf Sjöberg, 1951

Kubrick: “I have a very vivid memory of Miss Julie, which was directed in an extremely remarkable fashion.”

— interviewed by Raymond Haine, Cahiers du cinéma, July 1957

Édouard et Caroline

Jacques Becker, 1951

Kubrick: “They say Becker makes minor films, but Édouard et Caroline is nevertheless a ravishing thing.”

— interviewed by Raymond Haine, Cahiers du cinéma, July 1957

Casque d’Or

Jacques Becker, 1952

Kubrick: “I very much like Jacques Becker. His reputation for lightness has not stopped him from making an excellent dramatic film in Casque d’Or, which I saw many times.”

— interviewed by Raymond Haine, Cahiers du cinéma, July 1957

I Vitelloni

Federico Fellini, 1953

La Strada

Federico Fellini, 1954

Speaking in 1957, Kubrick said:

“I know only La Strada [of Fellini’s films] but that is amply sufficient to see in him the most interesting poetic personality of the Italian cinema.”

— interviewed by Raymond Haine, Cahiers du cinéma, July 1957

Seven Samurai

Akira Kurosawa, 1954

Frewin: “What struck me immediately while looking through this ‘Master List’ was the conspicuous absence of Akira Kurosawa. Stanley thought Kurosawa was one of the great film directors and followed him closely. In fact I cannot think of any other director he spoke so consistently and admiringly about. So, if Kubrick was cast away on a desert island and could only take a few films, what would they be? My money would be on The Battle of Algiers, Danton, Rashomon, Seven Samurai and Throne of Blood…

“Talking of Kurosawa, a poignant tale: Stanley received a fan letter from Kurosawa in the late 1990s and was so touched by it. It meant more to him than any Oscar would. He agonised over how to reply, wrote innumerable drafts, but somehow couldn’t quite get the tenor and tone right. Weeks went by, and then months, still agonising. Then he decided enough was enough, the reply had to go, and before the letter was sent Kurosawa died. Stanley was deeply upset.”

Smiles of a Summer Night

Ingmar Bergman, 1955

Kubrick: “The filmmaker I admire the most after Max Ophuls is without a doubt Ingmar Bergman, whose every film I’ve seen. I like enormously Smiles of a Summer Night”

— interviewed by Raymond Haine, Cahiers du cinéma, July 1957

Frewin: “Bergman’s star waned with Kubrick from the early 1960s onwards.”

Bob le flambeur

Closely Observed Trains (1966)

Jean-Pierre Melville, 1956

“The perfect crime film”

— Stanley Kubrick

Wild Strawberries

Ingmar Bergman, 1957

Throne of Blood

Akira Kurosawa, 1957

See the entry for Seven Samurai (1954).

La notte

Michelangelo Antonioni, 1961

Very Nice, Very Nice

Arthur Lipsett, 1961

[Kubrick reportedly asked Arthur Lipsett to create a trailer for Dr. Strangelove, but he declined. The designer of the film’s opening titles, Pablo Ferro, eventually cut the finished trailer and it is very much in the style of Lipsett’s work in Very Nice, Very Nice.]

Mary Poppins

Robert Stevenson, 1964

Kubrick: “I saw Mary Poppins three times, because of my children, and I like Julie Andrews so much that I enjoyed seeing it three times. I thought it was a charming film. I wouldn’t want to make it, but…

“Children’s films are an area that should not just be left to the Disney Studios, who I don’t think really make very good children’s films. I’m talking about his cartoon features, which always seemed to me to have shocking and brutal elements in them that really upset children. I could never understand why they were thought to be so suitable. When Bambi’s mother dies this has got to be one of the most traumatic experiences a five-year-old could encounter.

“I think that there should be censorship for children on films of violence. I mean, if I didn’t know what Psycho was, and my children went to see it when they were six or seven, thinking they were going to see a mystery story, I would have been very angry, and I think they’d have been terribly upset. I don’t see how this would interfere with freedom of artistic expression. If films are overly violent or shocking, children under 12 should not be allowed to see them. I think that would be a very useful form of censorship.”

— interviewed by Charlie Kohler in The East Village Eye, 1968, a few days after 2001: A Space Odyssey opened

The Siege of Manchester

Herbert Wise, 1965. Shot on film, made for BBC TV’s Theatre 625 (series 3, episode 8)

Kubrick saw parts of it during its initial (and only?) TV broadcast and the day after asked Herbert Wise whether he could bring the actual film reels to his house. Kubrick watched it all and asked Wise how he achieved the performances. View this interview with Wise where he recounts the story.

The Battle of Algiers

Gillo Pontecorvo, 1966

Kubrick: “All films are, in a sense, false documentaries. One tries to approach reality as much as possible, only it’s not reality. There are people who do very clever things, which have completely fascinated and fooled me. For example, The Battle of Algiers. It’s very impressive.”

— interviewed by Renaud Walter in Positif

Frewin: “Stanley raved (or what passed as raving with him!) about The Battle of Algiers, and Wajda’s Danton, over a lengthy period of time. When I started work for Stanley in September 1965 he told me that I couldn’t really understand what cinema was capable of without seeing The Battle of Algiers. He was still enthusing about it prior to his death.”

Closely Observed Trains

Jirí Menzel, 1966

The Fireman’s Ball

Milos Forman, 1967

The Anderson Platoon (La section Anderson)

Pierre Schoendoerffer, 1967

Kubrick: “I like to see documentaries. I very much liked La section Anderson, that film made by a Frenchman about an American platoon. I thought it was a terrific film. But personally I wouldn’t be interested in making something like that.”

— interviewed by Renaud Walter in Positif

Frewin: “Stanley had a high regard for Pierre Schoendoerffer. He watched La Section Anderson prior to Full Metal Jacket, and La 317ème Section (1964), and not only that but also Diên Biên Phú (1992) which Pierre sent over at Stanley’s request after I had tracked him down. They had a couple of conversations.”

Peppermint Frappé

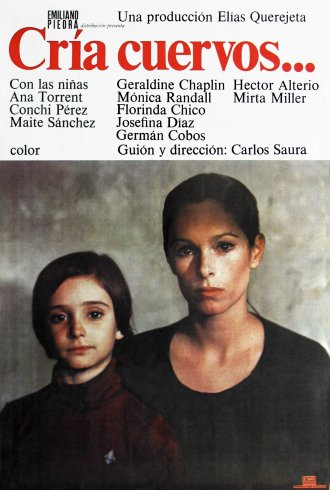

Carlos Saura, 1967

Kubrick, discussing Spanish cinema in 1980:

“I first encountered Saura’s work by chance and in a rather strange way one day when I got home quite late and turned on the television; a film in Spanish with subtitles, that I knew absolutely nothing about, and besides, I’d missed the first half hour. It was hard for me to follow and understand but, at the same time, I was convinced it was the film of a great director.

“I watched the rest of the film glued to the TV set and when it was over I picked up a newspaper and saw that it was Peppermint Frappé by Carlos Saura. Later I found a copy of the film, which of course I watched from the beginning and with great enthusiasm, and since then all of Saura’s films that I’ve seen have confirmed the high quality of his work. He is an extremely brilliant director, and what strikes me in particular is the marvellous use he makes of his actors.

“I’d also like to mention the great impression the young girl Ana Torrent made on me in the two roles I saw her play: in Erice’s film The Spirit of the Beehive, and in Saura’s Cría Cuervos. I dare say that in a few years she will be a woman of rare beauty – you can see it already – and a great actress. Besides these two directors I must of course mention Luis Buñuel, whom I have profoundly admired for many, many years.”

— interviewed by Vicente Molina Foix in El Pais – Artes, 20 December 20 1980, translated in 2013 by Georges Privet

[Kubrick asked Saura to supervise the Spanish versions of A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon and The Shining.]

If….

Lindsay Anderson, 1968

Rosemary’s Baby

Roman Polanski, 1968

Once Upon a Time in the West

Sergio Leone, 1968

Sir Christopher Frayling’s Leone biography (Something to do with Death) states on page 299:

“Kubrick admired the film as well. So much so, according to Leone, that he selected the music for Barry Lyndon before shooting the film in order to attempt a similar fusion of music and image. While he was preparing the film, he phoned Leone, who later recalled: ‘Stanley Kubrick said to me, “I’ve got all Ennio Morricone’s albums. Can you explain to me why I only seem to like the music he composed for your films?” To which I replied, “Don’t worry, I didn’t think much of Richard Strauss until I saw 2001!”’”

Ådalen 31

Bo Widerberg, 1969

Tora! Tora! Tora!

Richard Fleischer, 1970

Harlan: “I remember Stanley remarked: “How clever that the Japanese speak Japanese – what a difference it makes.’”

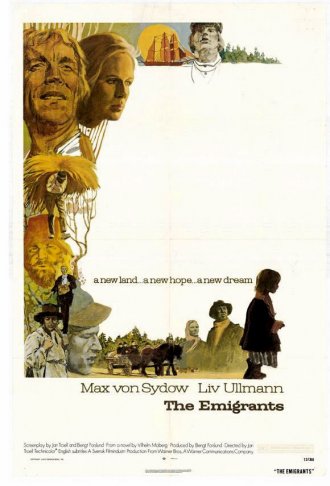

The Emigrants

Jan Troell, 1970

Harlan: “He adored The Emigrants. He was so enthused by the look of it that he hired the costume lady Ulla-Britt Söderlund for Barry Lyndon, who then worked with Milena Canonero. I remember Stanley wanting to talk to Jan Troell to congratulate him and ask him a few questions, and what happened so often to him when making these calls, after finally getting the person he wanted: ‘Is this Jan Troell?’, ‘Yes, who is this?’, ‘This is Stanley Kubrick’, ‘I bet you are’, and click, hung up. Then Stanley had to try again with: ‘Don’t hang up!’ etc.”

Get Carter

Mike Hodges, 1971

[According to Mike Kaplan, Kubrick said: “Any actor who sees Get Carter will want to work with [Hodges].”]

McCabe & Mrs. Miller

Robert Altman, 1971

Kubrick rang Altman to ask how he got the shot with McCabe lighting his cigar during the opening credits. See Breaking Point by Tony Hall, in Film & History, vol. 38.2, Fall 2008.

Harold and Maude

Hal Ashby, 1971

Harlan: “He loved Harold and Maude but I don’t know whether he ever spoke to Hal Ashby or not.”

Cabaret

Bob Fosse, 1972

Harlan: “Cabaret led to Marisa Berenson getting the part in Barry Lyndon.”

Cries and Whispers

Ingmar Bergman, 1972

Harlan: “He was very impressed and depressed by Cries and Whispers – he could barely finish it. I was with him.”

Deliverance

John Boorman, 1972

The Godfather

Francis Ford Coppola, 1972

The Spirit of the Beehive (1973)

“He watched The Godfather again… and was reluctantly suggesting for the 10th time that it was possibly the greatest movie ever made and certainly the best cast.”

— Michael Herr, Vanity Fair, 1999

Solaris

Andrei Tarkovsky, 1972

La bonne année

Claude Lelouch, 1973

The Exorcist

William Friedkin, 1973

The Spirit of the Beehive

Víctor Erice, 1973

American Graffiti

George Lucas, 1973

There are a few differences between the French and English editions of the Kubrick interviews that appear in Michel Ciment’s Kubrick book. (Kubrick subsequently revised the text for the first printing of the English edition.) In the French version, Kubrick says at one point:

“If I made as much money as George Lucas, I would not decide to become a studio mogul. I cannot understand why he doesn’t want to direct films anymore, because American Graffiti and even Star Wars were very good.”

— translated by Georges Privet, 2013

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre

Tobe Hooper, 1974

The Terminal Man

Mike Hodges, 1974

Kubrick: “It’s terrific.”

— quoted by Mike Kaplan in a Guardian piece. Also much-loved by Terrence Malick.

The Cars That Ate Paris

Peter Weir, 1974

Weir: “[Stanley] was a man who had a kind of internet before the internet: he knew things, he had contacts…

“Sometime in 1976 Warners approached me about directing a vampire movie. Stanley had very kindly recommended me to John Calley for the project, which he’d looked at himself. He’d seen my first two films, The Cars That Ate Paris and Picnic at Hanging Rock. Sometime earlier I’d written him a fan letter, though I didn’t say I was a filmmaker. I was enormously flattered and excited that he recommended me.

“I was in Hollywood trying to raise money for The Last Wave. Nothing I’d done had been released in America, and there I was having this wonderful meeting about this vampire picture. But I let it go. It wasn’t a humorous piece, and I thought, I can’t live in the world of this vampire movie for a year. So I went back to Australia and carried on as I had before.”

— from The Sound of Pictures by Andrew Ford. [The “Warner Bros. vampire film” turned out to be the TV movie Salem’s Lot (Tobe Hooper, 1979).]

Picnic at Hanging Rock

Peter Weir, 1975

See entry for The Cars That Ate Paris (1974)

In 2011, Weir said about Kubrick:

“[There] was one great thing that [Kubrick] instilled in me – that you can make a large, commercial film and not compromise your artistic values.”

— from Peter Weir Talks Trying To Crack ‘Pattern Recognition,’ Stanley Kubrick & ‘The Way Back’, Indiewire, 25 January 2011

Cría Cuervos

Carlos Saura, 1975

Harlan: “I saw Cría Cuervos in Zurich when it came out and loved it. I told Stanley what a great film it was and I remember his answer: ‘I am hungry for a great film – try to borrow a print.’ I called Primitivo Álvaro at Carlos Saura’s office in Madrid and told him how I loved the film and that Stanley Kubrick asked me call, etc etc – could we borrow a 35mm print? The answer was, “of course, we would only be too pleased” etc etc. I reminded him that it must have English subtitles. “Of course” was the answer.

“Two days later Emilio drove to the agent at Heathrow, at that time still temporary import formalities and stuff like this, we had the print ready on the next Saturday and invited a lot of people. Stanley and I ran the film. NO SUBTITLES! For the first ten minutes it doesn’t matter so much, one is enthralled by what we see – the little girl on the staircase, the woman coming out of the man’s bedroom, the girl calling Papa. He is dead. She sees the empty glass, takes it, washes it carefully in the kitchen and mixes the glasses. We are intrigued. Mum comes in, lovely little encounter before the masks of happiness slips from Mum’s face – and the girl is off to feed the pet. What a beginning.

“It became clear that there were no subtitles. Stanley first suggested to stop because it’s unfair. ‘Let’s just finish the reel’, someone said. I knew the film, briefed everybody between the reel changes about what we had seen, and we watched the whole film and loved it.”

Dog Day Afternoon

Sidney Lumet, 1975

One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest

Milos Forman, 1975

Annie Hall

Woody Allen, 1977

Close Encounters of the Third Kind

Steven Spielberg, 1977

Abigail’s Party

Mike Leigh, 1977

Eraserhead

David Lynch, 1976

[Listen to David Lynch himself tell the story.]

Girl Friends

Claudia Weill, 1978

Kubrick: “I think one of the most interesting Hollywood films, well not Hollywood – American films – that I’ve seen in a long time is Claudia Weill’s Girlfriends. That film, I thought, was one of the very rare American films that I would compare with the serious, intelligent, sensitive writing and filmmaking that you find in the best directors in Europe. It wasn’t a success, I don’t know why; it should have been. Certainly I thought it was a wonderful film. It seemed to make no compromise to the inner truth of the story, you know, the theme and everything else.

“The great problem is that the films cost so much now; in America it’s almost impossible to make a good film – which means you have to spend a certain amount of time on it, and have good technicians and good actors – that aren’t very, very expensive. This film that Claudia Weill did, I think she did on an amateur basis; she shot it for about a year, two or three days a week. Of course she had a great advantage, because she had all the time she needed to think about it, to see what she had done. I thought she made the film extremely well.”

— interviewed by Vicente Molina Foix in 1980

The Jerk

Carl Reiner, 1979

Harlan: “He didn’t think The Jerk was such a good film, but it is true that he considered (for a very short time) Steve Martin as an actor. Early days!”

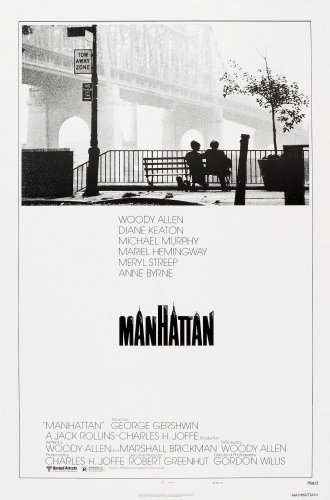

Manhattan

Woody Allen, 1979

Harlan: “‘Behind his black-rimmed glasses was the coiled sexual power of a jungle cat’ – we laughed out loud.”

All That Jazz

Bob Fosse, 1979

Alien

Ridley Scott, 1979

Scott mentions in the 2007 documentary Dangerous Days: Making Blade Runner that Kubrick admired Alien. Kubrick admired Scott’s work in commercials too.

Apocalypse Now

Francis Ford Coppola, 1979

Kubrick: “I think that Coppola was stuck by the fact that he didn’t have anything that resembled a story. So he had to make each scene more spectacular than the one before, to the point of absurdity.

“The ending is so unreal, and purely spectacular, that it’s like a version, much improved, of King Kong [laughs]. And Brando is supposed to give an intellectual weight to the whole thing…

“I think it just didn’t work. But it’s terrifically done. And there are some very strong scenes.”

— from Kubrick, enfin! by Michèle Halberstadt, Première (France), October 1987. Translated by Georges Privet, 2013

An American Werewolf in London

Jon Landis, 1981

Blood Wedding

Carlos Saura, 1981

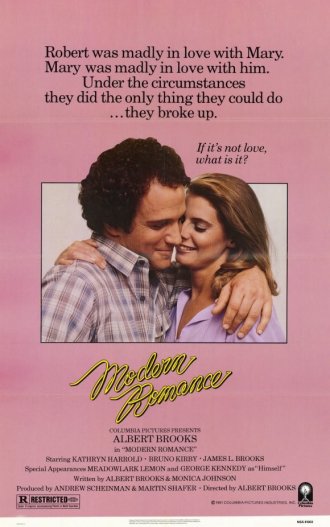

Modern Romance

Albert Brooks, 1981

[Brooks tells how Kubrick saved his life in Esquire, 1999.]

E.T. The Extra-terrestrial

Steven Spielberg, 1982

Danton

Andrzej Wajda, 1984

Frewin: “Stanley thought Danton was very nearly beyond criticism and ‘perhaps the finest historical film ever made’. He loved everything about it and said he would never tire of watching the scenes with Gérard Depardieu and Wojciech Pszoniak (‘I’d love to use that Polish actor in something’).”

[See also the entry for Seven Samurai (1954)]

Heimat

Edgar Reitz, 1984

Harlan: “Stanley was completely taken by Heimat. The idea of telling such an ‘impossible to tell story’ through the eyes of a bunch of simple villagers he considered completely new and brilliant. To show ‘heaven’ convincingly and without special effects on the top floor of a country inn and have the dead people observe ‘us’ – he was deeply moved. There are a number of other scenes like that. He was so taken by it that he hired the art director and costume designer for preparation of Wartime Lies (Aryan Papers). There are some specific scenes we saw together again and again (having videotaped the BBC2 broadcast) and I remember it all very well.”

Platoon

Oliver Stone, 1986

Kubrick: “I liked it. I thought it was very good. We weren’t too happy about our M16 rifle sound effects [on Full Metal Jacket], and when I heard M16s in Platoon, I thought they sounded about the same as ours.

“The strength of Platoon, is that it’s the first of what I call a ‘military procedural’ that is really well done, where you really believe what’s going on. I thought the acting was very good and that it was dramatically very well written. That’s the key to its success: it’s a good film. It certainly wasn’t a success because it was about Vietnam. Only the ending of Platoon seemed a bit soft to me in the optimism of its narration.”

— interviewed by Gene Siskel, Chicago Tribune, 21 June 1987

In an interview around the same time with Jay Scott from Toronto’s Globe & Mail, Kubrick said:

“I liked both Apocalypse Now and The Deer Hunter – but I liked Platoon more.”

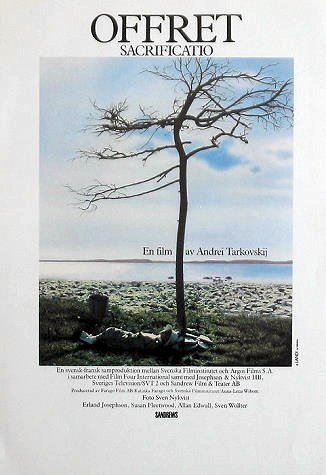

The Sacrifice

The Sacrifice (1986)

Andrei Tarkovsky, 1986

Harlan: “Very important.”

Babette’s Feast

Gabriel Axel, 1987

House of Games

David Mamet, 1987

Pelle the Conqueror

Bille August, 1987

Radio Days

Woody Allen, 1987

Harlan: “Stanley loved it, not so much because it is a great film, but because this was his childhood too.”

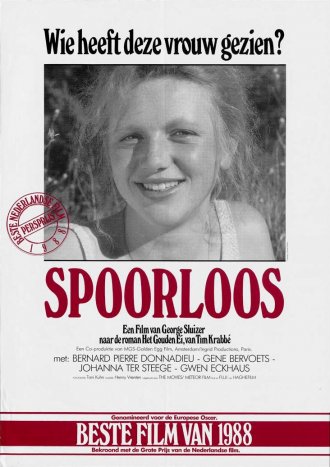

The Vanishing

The Vanishing (1988)

George Sluizer, 1988

Kubrick watched it three times and told Sluizer that it was “the most horrifying film I’ve ever seen”. Sluizer asked: “even moreso than The Shining?”. Kubrick replied that he thought it was.

Harlan: “The Vanishing was real – The Shining was a ghost film – a huge difference.”

Henry V

Kenneth Branagh, 1989

Harlan: “Stanley liked Branagh’s version much better than the old and old-fashioned Olivier version which he had on his 1963 list. He thought it was far superior.”

Roger & Me

Michael Moore, 1989

Harlan: “He greatly admired the guts[iness] of Michael Moore – substantial content and a major US figure.”

Dekalog

Krzysztof Kieslowski, 1990

Harlan: “I believe the only foreword to a book he ever wrote was for the scripts of Kieslowski’s Dekalog – and he did this with pleasure. A great masterpiece.”

The Silence of the Lambs

Jonathan Demme, 1990

Husbands and Wives

Woody Allen, 1992

White Men Can’t Jump

Ron Shelton, 1992

The Red Squirrel

Julio Medem, 1993

Pulp Fiction

Quentin Tarantino, 1994

Frederic Raphael recounts in this video clip how Kubrick recommended Pulp Fiction to him:

“He admired it very much, he said ‘it’s pretty good, okay?’

Frewin: “He thought it was slick.”

Boogie Nights

Paul Thomas Anderson, 1998

Anderson visited Kubrick in England during the Eyes Wide Shut shoot. Interviewed by Anderson’s own fansite Cigarettes & Red Vines in March 2000, he said:

“[Kubrick] had seen Boogie Nights and he liked it very much. He liked the fact that I was a writer director and commented that more filmmakers should write and direct. He said he liked Woody Allen and David Mamet and mentioned House of Games and Husbands and Wives – interesting how similar they are to Eyes Wide Shut.”

Harlan: “1993–1999 was such a hectic period – over a year intensive prep for Aryan Papers then the same again for A.I. – both ‘postponed’. These were tough times and watching films was mainly research. He saw fewer films during that time – still, he didn’t shut himself away and certainly saw The Silence of the Lambs and every Woody Allen film. But I can’t tell you specific titles as I could for the earlier periods.”

The Off List

Over the years, many uncorroborated claims have been made about Stanley Kubrick liking certain films. For the sake of comprehensiveness, where no other evidence exists or there are contradictory reports, I’ve gathered these titles outside the main Master List. Here is the ‘off-list”:

Lupino Lane

Comic two-reelers from the 1920s

It has been claimed (by the late Philip Jenkinson, in a 1981 edition of ITV’s Clapperboard) that Kubrick owned a couple of very rare prints of Lupino Lane films, and went out of his way to find them. Jenkinson suggested Ken Russell was a fan of Lupino Lane, too.

Anthony Frewin: “Take it from me, Stanley never had any Lupino Lane prints, certainly not in the years I worked for him.”

Things to Come

William Cameron Menzies, 1936

Frewin: “Despite the best efforts of both Arthur C. Clarke and myself Stanley could not see the merits of the film. He thought the narrative, such as it was, was subordinated to H.G. Wells’ ‘preachy’ belief that scientists were the only ones to be trusted to rule the world, that the film was essentially Wellsian propaganda.

“Two of the special effects supervisors on 2001: A Space Odyssey, Tom Howard and Wally Veevers, both began their careers under Ned Mann on the special effects of Things to Come. Also the film’s sound chief, A.W. Watkins, was the resident sound chief at MGM Studios when we were making 2001: A Space Odyssey.”

Universe

Roman Kroitor / Colin Low, 1960

This National Film Board of Canada half-hour film is reported to have influenced the special effects in 2001: A Space Odyssey, apparently “using the same panning camera effect for creating the planets”, and hiring narrator Douglas Rain to voice HAL.

Frewin: “Stanley didn’t think much of the film but thought the SFX showed promise and after talking to Wally Gentleman, who designed the SFX, hired him for 2001. But, alas, Wally, didn’t stay with us very long as he didn’t like Stanley interfering (!) with what he was doing!”

Ikarie XB-1

Jindrich Polák, 1963

Frewin: “Stanley had seen Ikarie XB-1 when he was researching and writing 2001: A Space Odyssey in New York prior to the move to London (along with anything else of remote interest that he could lay his hands on). It certainly wasn’t an inspiration to him though he did think it was a half step up from your average science-fiction film in terms of its theme and presentation, but then, as he admitted, that wasn’t too difficult in those days.

“I don’t think there were any futuristic or science-fiction films that inspired him. And the fact that cinema hadn’t delivered in these areas was a contributing factor in his making 2001.

“Stanley was an indiscriminate moviegoer (‘You can learn something from a bad film as equally as from a good film’), and I’m not sure how some of those films got on the list of his ‘fave’ films. He had a puckish sense of humour and may have been jesting at times. Often there may have been one shot or one sequence in an otherwise risibly undistinguished film that he thought was pretty good, but it’s a step too far including that film on a list of his favourites.”

Funeral Parade of Roses

Matsumoto Toshio, 1969

A number of people have pointed out striking (coincidental?) similarities between Matsumoto’s film and A Clockwork Orange, but no confirmation can be found. Neither Frewin or Harlan have any recollection.

Basic Training

Frederick Wiseman, 1971

Michel Ciment reported that Wiseman told him: “Kubrick watched Basic Training endlessly while preparing Full Metal Jacket.” Wiseman himself has repeated this claim in an interview with the Chicago Tribune. However those closest to Kubrick at the time cannot remember him viewing the film.

Frewin: “I’m not aware that SK ever saw this. I was getting all the films in at that time and I was never asked to get this. Anyway, we had Gus Hasford and Lee Ermey, both ex-USMC, on board to advise, and Michael Herr too.”

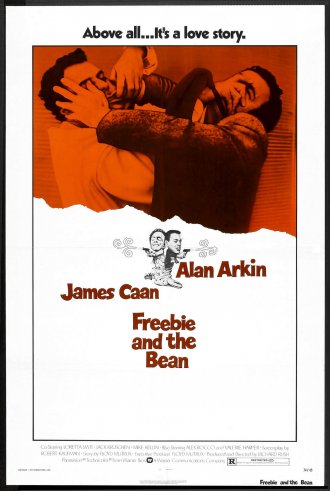

Freebie and the Bean

Richard Rush, 1974

[In a Rolling Stone article about Rush’s The Stunt Man it was claimed Stanley thought Freebie and the Bean was the best film of 1974.]

Who Dares Wins

Ian Sharp, 1982

Euan Lloyd, the producer of this anti-CND, right-wing action film, mentions on the commentary track of its newish Blu-ray disc that Kubrick was fond of the film. This claim is strongly contested:

Frewin: “Lloyd, as the gunnery sgt in Full Metal Jacket would say, is blowing smoke up our asses. That film is the antithesis of everything Stanley stood for and believed in.”

Barcelona

Whit Stillman, 1994

Stillman discusses Kubrick’s admiration for Barcelona on the Criterion commentary track for The Last Days of Disco.

Revisions

25 October 2013:

- Amended Very Nice, Very Nice entry.

- Expanded Metropolis entry.

- Added entries on La Kermesse Héroïque, Pacific 231, Édouard et Caroline, Miss Julie, Casque d’Or, Rashomon, La Strada, Seven Samurai, Smiles of a Summer Night, Throne of Blood, Mary Poppins, The Siege of Manchester, The Battle of Algiers, The Anderson Platoon, Peppermint Frappé, Once Upon a Time in the West, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, American Graffiti, The Cars That Ate Paris, Picnic at Hanging Rock, Alien, Apocalypse Now, Danton, Platoon, Pulp Fiction and Boogie Nights.

- Added The Off List sub-section.

Special thanks to Anthony Frewin for enjoying this memory exercise as much as Jan Harlan did a few months earlier.

Thanks also to readers of the original article who contributed a number of new leads, among them Phil Gyford, Tanmay Toraskar, Tobias Rydén, Michael Heilemann, Faisal Azam Qureshi, Jonathan Sanders, Peter Labuza, Soraya Lemsatef and especially Georges Privet, who provided a number of scans and translations of many fascinating foreign interviews with Kubrick that had not previously been available in English.

If you are able to point to any verifiable evidence of Kubrick admiring any films that aren’t listed here, you can send info to the author on Twitter via @kubrickfaves.

And in back issues of Sight & Sound

→

March 2009 —

Cover feature: Mister strangelove

From Lolita to Eyes Wide Shut Stanley Kubrick’s films often focus on sexual relationships. So why, asks Linda Ruth Williams, are they so unsexy?

+ Hall of mirrors

Kubrick’s unmade 1990s project Aryan Papers has now inspired an intriguing installation by the Wilson Twins that finally gives its star her moment. By Brian Dillon.

+ From romance to ritual

Barry Lyndon takes its inspiration from Thackeray’s source novel. But in Kubrick’s hands the tone – and the hero – are transformed. By Kim Newman.

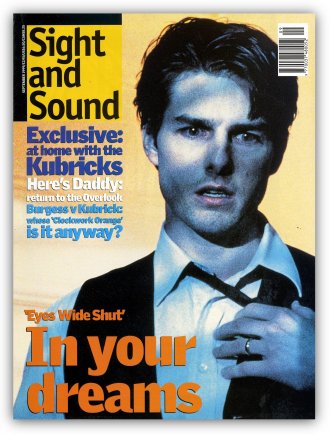

September 1999 —

Editorial: Stanley Kubrick 1928-99

The films of Stanley Kubrick have been central to what we think of as great cinema since the mid 50s. This special Kubrick issue was planned to coincide with the release of Eyes Wide Shut long before we learned of his death. His passing makes it more poignant that there are few other directors who would merit such treatment.

+ Resident phantoms

In some ways The Shining is the defining film of Kubrick’s latter years. Jonathan Romney revisits the Overlook Hotel for some perhaps overlooked clues to the director’s central themes.

+ At home with the Kubricks

So what was Stanley Kubrick really like? Nick James talks to three people who knew him better than most: his wife Christiane and two of his daughters, Anya and Katharina.

+ Too late the hero

In Eyes Wide Shut, the hero’s erotic odyssey is meant to be anxiety-provoking. A trap for sensation-hungry critics, the film follows the dream logic of 60s arthouse classics, argues Larry Gross.

+ Real horror show: a short lexicon of Nadsat

Did writer Anthony Burgess relish or rue working with Kubrick, asks Kevin Jackson?

Autumn 1987 —

Remote control

Dehumanising actor soldiers: Terrence Rafferty reviews Stanley Kubrick’s controlled vision of the Vietnam War, Full Metal Jacket.

Spring 1981 —

Kubrick and The Shining

P.L. Titterington discusses the evolution of Kubrick’s style and the language of his ideas.

Spring 1972 —

Interview with Stanley Kubrick

By Philip Strick and Penelope Houston.

Spring 1966 —

Two for the sci-fi

David Robinson on Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.