Web exclusive

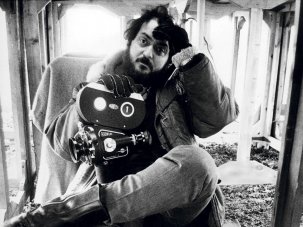

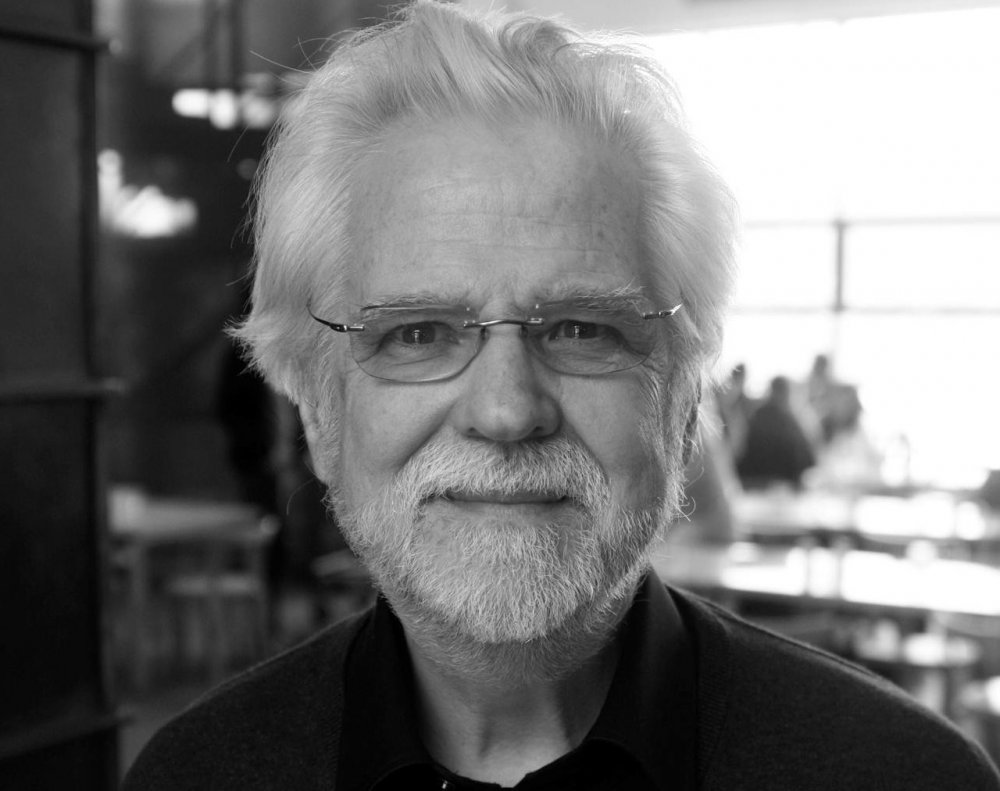

Jan Harlan

Credit: René Georg Johansen

Nick Wrigley: When did you start working with Stanley?

Jan Harlan: 1969. I saw Stanley almost every day for about 30 years or spoke on the phone with him, even though my office was either in his house in Elstree, or after 1979 very close by in St. Albans. He was such a busybody and could do so many things simultaneously that I don’t claim for a moment to have all the answers to questions you might ask.

I wasn’t up to his speed or intellect. The only area where I could be on a level playing field with him was music and table tennis. But I loved my job and working with him. It wasn’t always a walk in the park, but it was most satisfying.

So the start of your work with Stanley coincided with the beginning of his Warner Bros. contract?

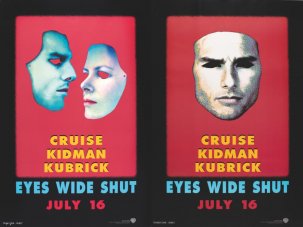

Yes. Did you know that his first contract with Warner Bros. was for Traumnovelle in 1970? – the film that became Eyes Wide Shut almost 30 years later. He ‘postponed’ it because he wasn’t happy with his script and A Clockwork Orange came along, the script was a ‘scissor job’ and he decided to do this.

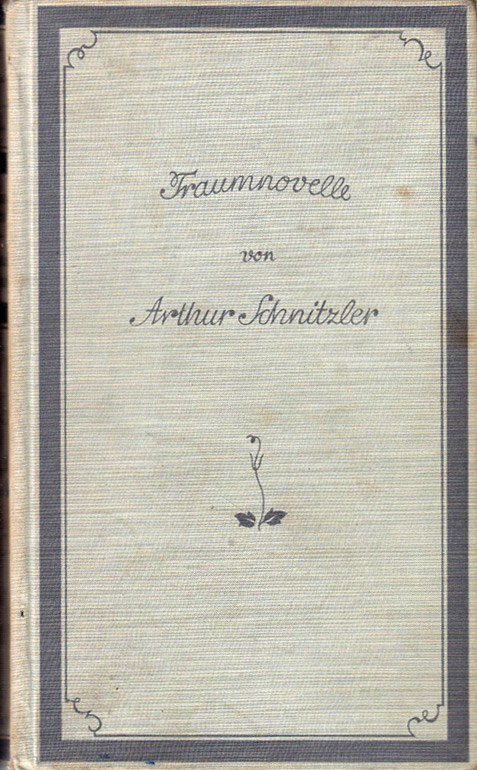

The first (1926) edition of Arthur Schnitzler’s Traumnovelle

Much later, before The Shining, he was on cloud nine with the idea of doing Traumnovelle as a low-budget arthouse film in black and white with Woody Allen in the lead – filming in London and maybe Dublin to mock New York. It was always New York and present time. Woody Allen, straight, as a Jewish doctor in New York: that was his plan. He abandoned it again because he was not satisfied with his script.

I am very happy to know that he considered Eyes Wide Shut his greatest contribution to the art of filmmaking – and I think he is the only judge that matters.

I’d heard about Steve Martin being mooted for the lead at one point – presumably in the early 80s – but not Woody Allen. How involved was Woody with it at this early stage?

He never spoke to Woody Allen. I met Woody in New York and told him all this and he said that Stanley had never asked him. But I know that Stanley had him in mind and he was pretty sure that Woody would play the part, had this become a project – it’s a great part and the two would have harmonised splendidly. Stanley loved Woody Allen’s films – “particularly the early funny ones” (as the aliens said).

All Stanley had to do was mention any actor he liked in an unchecked environment and a bit later he could read that his plan was to cast X for his next film.

Michel Ciment wrote that Stanley viewed all the latest films “with voracious curiosity” in his own 35mm projection room at home. Can you tell me more about Stanley’s viewing habits and your experiences as his viewing partner?

Stanley usually watched films on the weekend and he often invited his family or friends, me and my wife, etc. He saw so many films and was able to borrow prints old and new at weekends from most London distributors, many of which he had a great relationship with, and they were often keen to hear his thoughts. He had a reputation for returning prints properly: machine-rewound and punctually on Monday morning.

We sometimes had up to seven prints in the projection booth, particularly before a long weekend. There were a lot of films he would give up after ten minutes. Many times he would only see the first reel because if that somehow leaves you totally cold, the risk is too great to go on and waste another hour and a half. I remember we saw The Firemen’s Ball and Closely Observed Trains in one evening at Stanley’s house in Elstree, before he moved to St. Albans. Roman Polanski was with us.

Funny things pop into my mind thinking back to those days. My youngest son Ben was with us watching Polanski’s Tess. He was quite taken by it and wanted to be ‘grown-up’ about his uncontrolled emotions and said at the end with tears in his eyes: “I hope there will be a Tess 2”.

The Kubrick exhibition at Los Angeles County Museum of Art

You’ve spoken about Stanley’s exacting methods being part of an overarching desire for his films to last. He equated greatness in other filmmakers with longevity. Would you say a fear of mediocrity drove him?

No. It would be wrong to say it ‘drove him’. He just felt strongly that enough films are being made, he didn’t want to add to the pile of ‘just okay’ movies. That’s why it took him so very long to decide, to plan and prepare, to film and to edit. Fast he was not – neither was Vermeer – and then there were the films he prepared and abandoned.

You know so well how easy it is to make a film. To make a good film is a different matter, and a good film that enough people want to see is rather difficult. A great film is almost a miracle – like any great work of art, great painting, novel, symphony or building. And I dare to define greatness by the test of whether the work lasts and serves as a reference for future generations in order to have a look at our time. I believe Eyes Wide Shut will be truly discovered in 50 years, so will Edgar Reitz’s Heimat or many Ingmar Bergman or Woody Allen films, to name just a few. There are many more. These are [our contemporary equivalents of the works of] Charles Dickens, George Eliot, Thomas Hardy or Jane Austen, canvases of social life and intercourse.

Perhaps thanks to the internet and DVD/Blu-ray, Stanley’s films seem to be obsessed over by more people now than ever before. I’ve kept away from Room 237 because it looked a little silly. I wondered what you made of it?

I think it’s the silliest film ever. A complete rip-off. To say that hotel employees on the last day before closing – waiting with luggage for transport – is a reference to the Holocaust, is an insult to both Stanley and the victims of this greatest crime in human history. So are all other references to 1942. To go to the length of making drawings to prove that the large interiors of the hotel could never fit into the smallish place we see from the outside is a joke. Any schoolboy can see that! It’s a ghost film! Nothing [in Room 237] makes any logical sense.

Your ‘baby’ – the Kubrick Exhibition – has just completed a tremendously successful eight month run at LACMA. Are there any plans to bring it home to the UK?

It will open in Sao Paulo in October 2013. This is indeed the ‘baby’ of Christiane Kubrick and me and we are very proud of it. We were supported by the Kubrick Trust and the studios, particularly by Warner Bros.

We had over 240,000 visitors in Los Angeles. The exhibition was in Amsterdam, Rome, Paris, Berlin, Frankfurt, Gent, Melbourne, and Zurich before Los Angeles and we’ll open in Toronto in the Autumn of 2014. We are in touch with Krakow, Tokyo and Seoul for further engagements. We hope to bring it to London one day. The logistics and all details are dealt with by the Deutsches Filmmuseum, Frankfurt – without the competent and professional management they provide we could not do this.

Two last geeky questions, if I may? I’ve always wondered whether Stanley managed to see The Thin Red Line, which opened in the UK on 28 February 1999, a week before he passed away?

Not a chance he would have seen any film at that time. There was no time for that.

And finally, [Kubrick’s daughter] Katharina has said that Stanley ‘hated’ The Wizard of Oz. I’ve often wondered why, other than perhaps just a father’s disappointment his children didn’t prefer something more cerebral?

It was a “pretend dismay”. Disappointment is the wrong word in this context. All kids love The Wizard of Oz and The Sound of Music and he was smart enough to know that this is how it should be. I think he would worry much more if the preference of an eight-year-old had been The Wages of Fear.