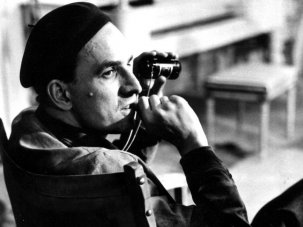

The movies enjoyed by my father, Ingmar Bergman, every day at three o’clock in his private cinema on the island of Fårö were often old black-and-white classics, well-remembered ones as well as forgotten ones. Stepping through the rust-coloured door of the barn – leaving the blinding Fårö light for the embracing gloom of the cinema – is a special experience. At first, the darkness seems compact. You grope your way to your seat, sit down and let your eyes adjust to the sparse light. Now the huge tapestry depicting The Magic Flute on Fårö slowly emerges. One August evening in 1974, beneath a full moon, Ingmar’s opera film The Magic Flute had its very first screening in the old barn, whose transformation into a cinema had just been completed.

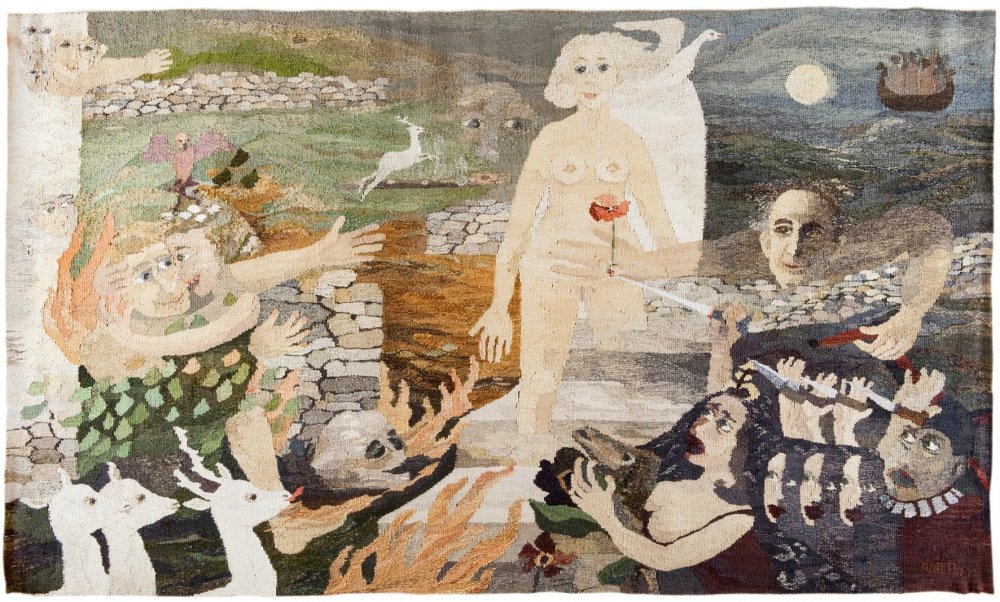

In his essay collection Ballaciner, J.M.G. Le Clézio describes the moon, lit by the sun, as being the prototypical film projector – and the darkness of night might be a first camera obscura lit by other worlds. Light and darkness are the prerequisites for film, and guess what – on the tapestry a moon is floating in a pale, mysterious light. We also behold the Queen of the Night, white-breasted and dressed in black, brandishing her knife. Here in this cinema, the Queen of the Night reigns – but over there is the wise Sarastro, who has made a pact with the sun and the light. So we find ourselves in the presence of both these opposite forces.

Anita Grede’s tapestry The Magic Flute on Fårö, the only decoration inside the cinema, depicting a mix of mythological and local landscape.

Credit: Kuba Rose

I have tried to calculate the number of hours that Ingmar must have spent in his cinema watching movies – sitting, or rather lying, in the armchair in the front row, his feet on the footstool.

Imagine: every day after his noon nap, Ingmar would get into his red jeep and arrive at his cinema just before three o’clock. He would spend two hours there. (The exception was Saturday, when the screening started at two o’clock.)

A movie six days a week, from May to October, for roughly 30 years; in addition, for three days a week throughout July he would invite his large family, who would be staying on Fårö, to evening screenings. He may have spent around 8,000 hours in his cinema. Little wonder, then, that Ingmar’s presence can be felt there.

On 14 May 1944, Ingmar set up a rented film projector at home in the Stockholm suburb of Abrahamsberg, where he occupied a tiny two-room flat with my mother, dancer Else Fisher. (She thoroughly documented this event in her diary.) He was 25 and on the rise. They watched Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1919), Murnau’s Faust (1926) and Chaplin’s Easy Street (1917). “Fun!” my mother noted in her diary (though renting a projector and film wasn’t cheap). Having your own cinema – is that as enjoyable as having your own puppet theatre? As being able to open up your magic box whenever you like?

Ingmar welcomed people to share a movie experience with him in the way that others (normal people) invite their friends over for a meal. Dinners with Ingmar were rare, but sharing a film with him meant an invitation to get together. And often to talk – there were light-hearted and often lengthy post-cinema conversations in the sheltering gloom of the barn. Ingmar often joked about the cinema being a therapist’s couch.

Easy Street (1917)

The screening always adhered to a special ritual. If there were many of us attending, we would gather at the blue bench by the wall of the barn. Ingmar was almost always the first to arrive, sitting there waiting for us. Hugs. “Well then, shall we go in?” There would be light-hearted talk (about who’d got tick bites) as your eyes readjusted into cinema mode, and a short presentation of the film at hand. Sometimes we were issued with a neatly handwritten note listing the week’s films.

“I take no responsibility whatsoever for this film – you are here at your own risk,” Ingmar would say, sinking down in his armchair beneath his spread-out leather jacket, raising an arm to let Ingalill – his right-hand woman and projectionist – see his rotating finger. The gesture so admired by his grandchildren – the gesture that means that the lights can go down, the projector can start up and the film can begin.

Rules of engagement

The three o’clock cinema was thus an institution. There were rules, of course (both explicit and implicit):

1. Punctuality

Everyone is familiar with Ingmar’s penchant for punctuality.

2. Continuity

Going to the movies on rainy days alone, or just watching especially interesting films, was out of the question. So was spending sunny days on the beach, or choosing to skip the more challenging films. What you needed, in short, was obsessive cinematic dedication. (Perhaps this dedication also included getting close to a father who had previously been absent from our lives, but that’s another matter.)

3. Willingness

Ingmar often told us it pained him to see how Liv Ullmann’s dachshund expressly revealed its boredom with a film. In other words, you weren’t allowed to get bored or fall asleep. I particularly recall a documentary about a sawmill. The film just went on and on – footage of logs being split in perpetuity.

Credit: Kuba Rose

Some films returned every summer. These were the most loved ones: Ariane Mnouchkine’s fabulous Molière (1978). Alain Corneau’s Tous les matins du monde (1991), presenting moving questions about what artistry and music entail. Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950). Jacques Becker’s Casque d’or (1952), starring Simone Signoret, a staple when it came to thoroughly romantic films.

On each birthday, 14 July, there was a Chaplin film – The Circus (1928) was probably the one most dear to Ingmar. Often there was a short opening film. Victor Bergdahl’s animated Kapten Grogg cartoons, made at home on his kitchen table, were dearly loved by Ingmar. (There were also Kapten Grogg festivals for the grandchildren.) For me Ingmar often screened his short Karin’s Face (Karins ansikte, 1983) about his mother, my beloved grandmother.

And finally, the high point of every summer: Victor Sjöström’s The Phantom Carriage (Körkarlen, 1921). I think its closing line served as a memento to Ingmar: “Lord, please let my soul come to maturity before it is reaped.”

He Who Gets Slapped (1924)

Another Sjöström film – his first Hollywood production – was the last film I watched in the cinema with Ingmar, at Easter in 2006. He Who Gets Slapped (1924), starring the wonderful Lon Chaney, is set in the world of the circus. This was MGM’s first production, and the roaring, ravenous circus lion doesn’t just appear in the film, but also makes its debut in MGM’s famous production logo. It’s a film with connections to [Bergman’s own] Sawdust and Tinsel (Gycklarnas afton, 1953). Shame and humiliation, the pain of the white clown, the tension between bourgeois life and the life of the artist, the clown and the rage – it’s all there in this masterful silent film, made by the director most dear to Ingmar.

Silent laughter

I will never forget how we all laughed at Buster Keaton’s The General (1926). A train ride with open carriages – Keaton exits a tunnel, unshakeably serious, his face black with soot.

The room explodes with laughter. Finally Ingmar gets to his feet, laughing until he’s out of breath, exhaustedly wiping his eyes.

As a moviegoer, Ingmar was practically childish. And a professional. And excited. He didn’t indulge in intellectual analysis or the reflections of a cineaste. The greatest praise that could be bestowed on a film was: “The best flick of the summer – a real Fårö film.”

He saw the films made by most of his younger colleagues. I was struck by the generosity of his comments. He was often genuinely sad and hurt if you didn’t like the film on offer.

Credit: Kuba Rose

I have often pondered what went on at the three o’clock cinema – what was the fascination for Ingmar, sheer film interest aside? What was it that captivated him in this way?

Back to Le Clézio: “Film is always now.” Though, in fact, everything is over – the actors are somewhere else. Or, as Ingmar often exclaimed while watching an old film, “To think that everyone we see is dead!”

It felt as though, in the company of his old black-and-white films, he allowed himself to be cradled in a special room between the present and the past – a kind of in-between. Psychoanalysts talk about the ‘transitional area’ that has to be reached in order for growth and healing to occur; in an artistic context this is a place for playfulness and creativity. Ingmar’s cinema on Fårö is like one of those magical transitional areas: a room between light and darkness, between then and now – and between the living and the dead.

Translated by Anders Lindahl.

-

The 100 Greatest Films of All Time 2012

In our biggest ever film critics’ poll, the list of best movies ever made has a new top film, ending the 50-year reign of Citizen Kane.

Wednesday 1 August 2012

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.