Bibi Andersson was one of the most luminous apparitions in Swedish cinema, and her blonde character was often a guarantee for life in the many films she acted in. In Ingmar Bergman’s So Close to Life (Nära livet, 1958) she was the happiest of the women in confinement. In The Seventh Seal (1957) she and her little family are saved from the Black Death, which harvests most of the other characters’ lives. In Persona (1966) she is the stubborn defender of all the possibilities of life to the actress she is nursing who for some time has chosen to expel parts of her life. One could continue with more examples from the near-one hundred parts that Bibi Andersson got to shape on film.

In real life, too, Bibi to the very last refused to give up. Ten years ago she suffered a double stroke, which obliged her to a life as a convalescent, more or less exempt from words. Her persistent defiance, which during this long period was directed towards the final inevitability of death, was also a character streak throughout her life.

Bibi grew up in a politically radical home. Her strong political dedication was also present throughout her life. In her memoirs she depicts the objectivity with which her choice of profession was received at home. The schoolgirl Bibi had made an ability test, which showed that “an artistic profession was not unimaginable, as the talent for expression surpasses normal intelligence.” Hence the family agreed that a career as an actor was not out of the question. So Bibi entered a theatre school, and shortly afterwards was accepted onto the acting course at the Royal Dramatic Theatre.

Director Ingmar Bergman, actors Bibi Andersson and Victor Sjöström and DP Gunnar Fischer shooting Wild Strawberries (Smultronstället, 1958)

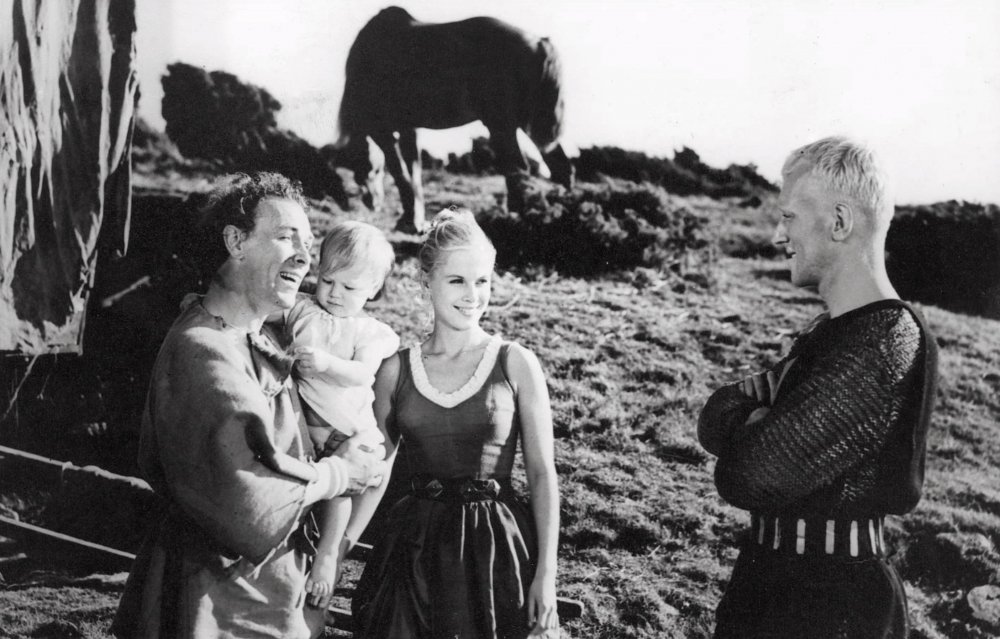

Andersson as Mia, the jester’s wife, with Max von Sydow as Antonius Block, the knight, in The Seventh Seal (1957)

She had already had some small parts in film as an extra when, in 1952, Ingmar Bergman was directing a couple of commercials for soaps. Bibi was hired for one of them, and she was according to Bergman “terribly sweet in a blue gown. She had already from the beginning a crown of a princess.” Not long after Bibi moved to live with Bergman, which made her mother very upset. “Ingmar was almost the same age as my mother,” Bibi has declared. “This made her so furious.”

Bibi then moved with Bergman to the Municipal Theatre in Malmö, where over time she got bigger and bigger stage roles. But she will most probably be remembered as a screen actress, and indeed as one of ‘Bergman’s girls’, in films like Smiles of a Summer Night, The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries, The Magician, Persona (for which she won the first of her four Guldbaggens, the Swedish Oscars), Passion and The Touch.

In a short film I made in 2009 (Images from the Playground / Bilder från lekstugan) Bibi jokingly complained about her faith as a perpetual blond survivor in Bergman’s films. “I could think; he doesn’t see my capacity,” she said. “I always got the parts of nice schoolgirls, but I wanted to play the kind of parts he gave to Harriet (Andersson) and Liv (Ullmann). Ingmar passed me by, I could think. Though I really got very beautiful parts, for which I can be just happy and thankful. I can’t remember they were specially difficult to play either. Probably because Ingmar always made it so easy for us.”

As Britt-Marie, with Jarl Kulle as Don Juan in The Devil’s Eye (Djävulens Öga, 1960)

Persona (1968)

Her work with Bergman brought Bibi out into the world, but her international career was never so memorable, even though she got to work with directors like John Huston (The Kremlin Letter, 1969) and Robert Altman (Quintet, 1979). Some of her stage parts have stayed in the mind more strongly – in classics like Romeo and Juliet, or as the younger woman in Bergman’s production of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, or in Long Day’s Journey into Night, again directed by Bergman. There she played mother to Thommy Berggren, who had almost the same age as Bibi, an actor she also worked with on Miss Julie, both on stage and in a 1969 TV movie.

Many male directors have had influence on her life: Bergman, Kjell Grede (her husband from her first marriage), Milos Forman. In a 2004 TV film Bibi remarked: “I won’t deny it or lie about it; but clearly, in this world ruled by men, especially within my profession: if you don’t have a man behind you, you’re nothing.”

As Eva Vergérus in Passion (En passion, 1969)

As Karin Vergerus, with Elliot Gould as David Kovac, in The Touch (Beröringen (1971)

Bibi also had a strong social and political dedication. She took the initiative for the association Artists for Peace in Sweden, in connection to the war in former Yugoslavia. And she stood behind the charity project Open Road – Sarajevo, travelling to the city in the middle of this burning conflict. “I think people are capable of commitment to a higher degree than what they might believe themselves,” she said. “Longing can be a strong power and drive.”

For all of us who have met Bibi in real life or just on the silver screen there is no end. We can, whenever we like, continue our acquaintance through some of the many films which she enriched with her luminous presence. Bibi is an actress to remember, both for her art and for her engagement outside the world of theatre and cinema.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.