It’s unsurprising that many myths and misconceptions have arisen surrounding Ingmar Bergman, that of the terminally gloomy Swede being merely the most prevalent. Here, after all, is someone acknowledged as one of the greatest filmmakers of all time yet viewed by those none too familiar with his body of work as a whole as a forbiddingly lofty, aloof philosopher rather than an artist or entertainer. (Even a feature in last month’s Sight & Sound claimed that some of Bergman’s films might today “be considered so wilfully opaque and mired in symbolism as to be past the point of parody”.)

The Touch screens as part of Ingmar Bergman: A Definitive Film Season at BFI Southbank, London, from 23-28 February 2018 and at select UK cinemas. It is released on BFI DVD and Blu-ray on 23 April.

Here, too, is someone who, notwithstanding two volumes of mischievous, possibly unreliable autobiography, kept his personal life private, even as he poured his own emotions into his films. Someone who preferred the company of a close circle of friends and collaborators, and spent much of his life reclusively on the island of Fårö. And someone whose best known film – The Seventh Seal (1957) – is quite atypical (he made few films which were allegorical or set in the distant past), and which has therefore reinforced many misunderstandings about his work.

Look closely at Bergman’s oeuvre in toto and you won’t find someone constantly obsessing about death or God’s silence. While death occurs as frequently as it does in most cinema (where death is almost as ubiquitous as it is in real life), it isn’t a central concern in most of his work; and questions of religious faith feature in still fewer movies, and hardly at all after Winter Light (1962).

Likewise erroneous is the notion that his work is laboriously slow (most of his films zip along for around 90 minutes) and difficult to understand (only Persona, released in 1966 and by far his most radically experimental film, might fit that description). Bergman’s popular reputation, then, based more on impressions of his prolific output than on close familiarity and measured consideration, is a mixed blessing.

One victim of this mythification has been The Touch (1971). On those rare occasions when it has even been mentioned, the film has often been lumped together with the 1950 thriller This Can’t Happen Here (aka High Tension), a commercial chore from a script by Herbert Grevenius which Bergman later disavowed and requested not to be shown. That film, he claimed, he’d known from the start would be rubbish; The Touch is a very different creature.

True, Bergman says little about it in his autobiographies, other than to opine that he’d bungled the story and to list it alongside Face to Face (1976), The Serpent’s Egg (1977) “and so on” as projects that ended in “embarrassing failure” compared with the achievements of Tarkovsky, whom he greatly admired. But should we really trust the opinion of a film’s creator, whose feelings are surely inflected by the experiences of making it and witnessing its passage into the world?

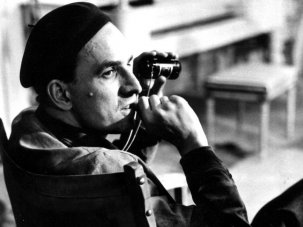

Ingmar Bergman (second from right) on location for The Touch

If the former was not especially problematic, the latter was something Bergman probably preferred not to recall in detail. Receiving mixed reviews, The Touch performed poorly at the box office; thereafter, unlike the works that followed and immediately overshadowed it – Cries and Whispers (1972) and Scenes from a Marriage (1973), both critical and commercial hits – it was seldom revived, virtually becoming a ‘lost’ film. It’s likely that few who mentioned it in passing in articles on Bergman had seen it; all they knew was that it starred Elliott Gould and Bibi Andersson, was Bergman’s first English-language movie, and surely must have deserved its box-office failure, given the unfavourable reviews.

Look beyond the mythology, however, and a rather different picture emerges. One of the most successful European directors of the late 50s and 60s, Bergman had been much courted by Hollywood but, preferring to make films about what he knew best – people like himself and his acquaintances – he had repeatedly rejected such offers.

The Touch, however, was a different proposition, since it allowed him to film in Sweden. In 1964, in London, Bergman had encountered Morton Baum of the American Broadcasting Company; it was about to set up its own production department, ABC Pictures, which would specialise in faintly offbeat fare like Take the Money and Run (1969), They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969), Straw Dogs (1972) and Cabaret (1972). Bergman and Baum agreed that he’d write and direct a film for ABC; The Touch was the result.

For the lead actor, the company proposed Paul Newman, Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford, but Bergman cast Gould, whom he’d recently seen in Getting Straight (1970). Otherwise, the film was par for the Bergman course: Bibi Andersson was the lead actress, Max von Sydow played the third main character, the cinematographer was Sven Nykvist and the chief technical personnel were all regular collaborators.

Two versions of the film were made: one in Swedish and English, the other wholly in English, made at the Americans’ insistence, which included scenes of the Andersson character conversing with her family and other Swedes in a language that was absurdly not their own. This, sadly, was for many years the only version available; even now, YouTube proffers a dismally soft-focused copy of this version complete with floating Hungarian subtitles. Small wonder the film’s reputation sank so low.

The initial response, however, was far from wholly negative. The Swedish reviews were mixed. In America, while Vincent Canby and Roger Ebert expressed disappointment, Richard Schickel and Molly Haskell praised the film. In Britain, it received strong support from Jan Dawson in the Monthly Film Bulletin and Nigel Andrews in Time Out. So it was not altogether surprising when, four decades later, a restoration of the original bilingual version met with a very warm welcome: despite all those rumours to the contrary, here finally was a film that undoubtedly belonged to that unbroken string of masterworks running from Persona in 1966 to (pace Bergman’s own disappointment with it) the 1976 TV series Face to Face.

The Touch (1971)

Bergman’s description of The Touch as “a love story” is also rather misleading. When Karin (Andersson), a seemingly happily married mother of two, impulsively decides to go to bed with David (Gould), an archaeologist visiting Sweden whom her doctor husband Andreas (von Sydow) has befriended, she tells him she doesn’t know why she’s doing so or whether she loves him. Still, she behaves as if she loves David, tolerating his volatile mood swings, his clumsy, even brutish sexual overtures, his peevish immaturity and increasingly jealous hostility towards Andreas – who himself begins, after a while, to suspect that his wife is up to something. Karin, meanwhile, dreams of an ideal, whereby her double life will be accepted by both men, so that her one “good, wise life” can help them all. Needless to say, her dream is doomed to failure.

The film is sometimes characterised as the story of a romantic triangle, but it’s more accurate to stress its constant focus on Karin. Her point of view and emotions are what interest Bergman throughout: her happiness with Andreas and her children; her elation at being so suddenly courted by David (who rashly tells her, when invited to dinner by Andreas, that he fell in love when he first saw her some weeks earlier at the local hospital, alone and grieving for her mother); her confusion at the cold rebuttals which regularly punctuate David’s more affectionate behaviour; her anxiety and indecision over betraying and possibly losing her family; and her determination to remain true to herself… whatever that may mean.

The Touch is not so much a traditional love story as a film about the quest for real human contact: the need and desire for love, and the difficulty of giving, accepting and sustaining it. Typically, Bergman eschews romance, knowing that humans sometimes act according to self-destructive impulses: Karin is not only seduced by David’s forthright – but, to us, self-deluding – declaration of love; she’s also clearly drawn to his moodiness, vulnerability and solitude (Jewish, he tells her he lost his family in the Nazi death camps). Likewise, she may believe her marriage of 15 years is a happy one, but her swift, unthinking, excited response to David’s possibly booze-fuelled confession may suggest otherwise; indeed, perhaps unconsciously she’s already been looking for something to enliven her life.

Little of this is explicit in the script: Bergman’s characteristically unflashy, pared back but precise mise-en-scène enriches the film’s levels of meaning. Nykvist’s use of Eastmancolor may suggest naturalism – the mood, now autumnal, now wintry, is beautifully sustained – but in the early scenes Karin’s bright red outfits (worn even to the hospital, when she arrives 15 minutes late to bid her dying mother farewell) stand in telling contrast to the whites, greys and beiges of her surroundings, suggestive of a nonconformist spirit seeking some kind of freedom.

The Touch (1971)

The opening credits shots of the small coastal town where she and Andreas live initially look like slightly touristy images – a castle, picturesque streets – until it becomes apparent that old, solid stone walls are everywhere, foreshadowing the themes of imprisonment and separation. Likewise the use of sound: the scenes of Karin’s cheery interactions with her children over breakfast and of her doing the housework are accompanied by pop music on the radio, gratingly bright, banal and repetitive, highlighting the mechanical routine of her daily existence. And whenever she visits David for a tryst in his glum green apartment, there in the background is the constant noise of demolition and construction work, an echo of his own turbulent temperament.

None of this is ‘symbolism’ as such; Bergman is simply using the various signifiers at his disposal to enhance mood and meaning. Even some delicately deployed images of gardens and flowers, which have led some commentators to allude to Eden, Satan and temptation, would seem to have more to do with evoking a carefully cultivated ‘freshness’ in Andreas and Karin’s marriage and, in the case of a hot-house, a stifling claustrophobia. Indeed, the only evident symbol is a medieval wooden Madonna discovered in a church where David is working; once removed from behind the wall that concealed it for centuries, the figure falls prey to the elements, just as Karin’s bid for love and freedom carries its own risks.

The Touch is rich in ironies, paradoxes and ambiguities. We never learn who sent letters to Andreas (if indeed anyone did…) alerting him to Karin’s affair; similarly, the details of David’s past and his life back in London remain tantalisingly vague, as they are to Karin herself. One especially significant conversation between David and Andreas is subtly intriguing as to its possible nuances and consequences, in terms of why they say what they do, and who they think can hear them.

Since Bergman generally strives to understand what makes even his minor characters tick, Karin, Andreas and David all have their reasons… and their virtues and flaws. Notwithstanding Karin’s feelings for him, however, David is at heart sad, surly and self-obsessed, alert only to his own needs: even when he inadvertently stumbles upon Karin in her grief at the hospital, after making a perfunctory offer of help he simply stares at her, tactlessly, until she’s driven to demand he leave her alone. Such insensitivity doesn’t bode well – but even when she’s later reminded of the encounter, Karin can’t prevent herself responding to his self-serving efforts, however boorish or inappropriate given his status as a dinner guest, to reach out and seduce her.

The Touch is a fine companion piece to the film that preceded it: En passion (1969), which is now generally known in English as The Passion of Anna but would be far better translated as ‘A Passion’ as its protagonist is not Anna (Liv Ullmann) but the reclusive divorcé Andreas (von Sydow), who undergoes a passion in the biblical sense of a process of suffering. He, like Karin, is touched by the interest shown in him by a new acquaintance, and responds by trying to give – and hence receive – love; like Karin too, he finds that such an ambition is not that easy to achieve, since other people are not always as straightforward or accepting as we’d like them to be.

Like The Passion of Anna, The Touch ends on an image of solitude, indecision, immobility – but also of freedom and open-endedness. A pause before an unknown future; a moment of truth and self-awareness. A glimmer, then, of hope.

Watch an exclusive clip from The Touch (1971)

-

Sight & Sound: the March 2018 issue

Greta Gerwig on Lady Bird, plus girl friends in the movies, The Shape of Water, Loveless, The Touch, A Fantastic Woman, Dark River and our...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.