1. Oxford and Sequence magazine

CD: Before we start talking about you joining Sight & Sound and the BFI, around 1950, could you briefly tell us about what you did before that?

PH: Well, I was – what was I when I joined the BFI? Twenty-two, I suppose. I went up to Oxford in 45. This was this mixed-up, post-war Oxford. I went straight from school. Actually, I’d done my degree by the time I was 20. Most people don’t even start by then, now do they? I got a job working as a researcher on the official war history, which was quite interesting; very badly paid; and I actually took a salary cut to go to work at the BFI. So, that is my pre-BFI experience. Unless you want to go right back to…

CD: What was your degree in?

PH: Modern History.

CD: Can you tell us about your pre-BFI film criticism at Sequence [magazine] and how you got involved with Lindsay Anderson and all the others?

PH: [Laughs] I’ll tell you my first meeting – or, not meeting, my first sight of Lindsay, because it’s a nice story. It was a film society programme at Oxford, of course, and the film was – I think it must have been Thy Soul Shall Bear Witness [aka The Phantom Carriage, 1921], that very gloomy, Swedish silent classic. And it would have been one of those scratchy, grainy, grey, awful 16mm prints the BFI were sending out. So, it didn’t even look good, and after about halfway through the picture the audience did that Film Society thing of laughing at the (sub)titles. And I’m sure the titles were pretty ridiculous.

This person sitting around three rows ahead of me got up and yelled. Stood up and absolutely yelled: “Stop laughing. It isn’t funny!” Unfortunately, he was wearing a very long, very bedraggled army greatcoat, and as he stood up he tripped over his coat. So the people he was sitting next to and shouting at had to prop him up to stop him falling over, which spoiled the effect. Well, that of course was Lindsay. And a Lindsay moment in every detail.

I actually met him, I suppose, a little bit later at a party or a Film Society do, but hat was the first time I saw and heard Lindsay. I was editing and writing film reviews for Isis, the university weekly undergraduate paper.

Sequence was started by the Film Society. The sort of forgotten man of Sequence was Peter Ericsson. Nobody remembers about poor Peter. The legend is of course that Gavin [Lambert] and Lindsay started it together at Oxford and I think they did nothing to discourage that legend. And Gavin had actually left Oxford because he didn’t like his tutor, C.S. Lewis. But he is writing in Sequence too. I’ve forgotten that.

We took over the magazine when the Film Society lost interest, after one issue. Then Lindsay and Peter went down a term ahead of me for some reason and they took the magazine to London where Gavin already was. That is in a nutshell the early days of Sequence. By that time I was working for my school and I thought, well, I’d had a lot of fun working for Sequence and that was that. But it sort of reappeared. Anything more about Sequence?

CD: Nobody knows about how the magazine was made. Were there passionate discussions between you…?

PH: I suppose there must have been. It’s tiny when you look at it, but a tiny little object it is. It was always a pretty small magazine. I suppose we had discussions; we must have done. [Laughs.]

GNS: Who financed it?

PH: That I’ve never known. That is a great mystery because the Oxford printers, you know, were very tolerant. But somebody must have paid the bills. I do remember at once point being told that we must each pay up a tenner. And that was quite a lot of money, a tenner, in those days. And I produced mine and, to my rage, neither of the others did. This was the awful girls’ public school education – when you were asked for money you had to produce it.

CD: At what stage did you realise that you wanted to be a film critic?

PH: Oh, God. Do you want another bloody story?

CD: Yes.

PH: I went up to Oxford, fully determined to have an academic career. I was very good at it. I didn’t think of the teaching bit, which I wouldn’t have liked at all. But I was imagining myself doing a lot of fascinating research. And I had a scholarship interview at Cambridge, where I’d just met two people, and then I went to Somerville and was shown into this long room with about 16, 18 women dons.

At the end of the interview they got to this sort of ‘What do you want to do?’ question and I thought, well, they must get awfully bored with all of us bright girls turning up and saying: “Oh, we want to be just like you.” And to my surprise I said: “I want to write about films,” which I didn’t really, I thought in a way. And they looked very startled and very shocked. The principal said: “I don’t think we’ve ever had a film critic.” They’d had Dilys [Powell], of course. And: “Why?”

And I honestly wasn’t quite so barmy that I said: “Because I’d love a job where you’re paid to watch films all day.” I wasn’t quite that demented, but I produced actually quite a good answer for off the cuff. I said: “I think that film is obviously the art of the century and I think we can see that by now. I don’t think I’m creative, but I would like to – it would be very interesting to comment on where it will go in the next 10, 15, 20 years.” And they looked a bit startled. And I said: “If sound cinema in a little more than a decade can produce Citizen Kane, God knows where cinema will go in 20 years.”

And at the words ‘Citizen Kane’, the most extraordinary racket started among the 18 dons. The older ones were saying: “What’s the child talking about? I can’t understand a word of it.” And the younger ones started actually coming to blows. Cries of “masterpiece” and cries of “that awful man – that awful film,” and they were banging the table, shouting at each other and after a minute or two it got louder and noisier and the principal gave me an absolutely horrified look and said: “Well, obviously this interview’s over, out you go.” As I walked out of the door, I was cheered by the cry of “Rosebud!” coming from the throng.

I crept out and I thought: “Well, you really have done it. Why didn’t you tell them the truth? Why didn’t you say that I just want to be a nice don like you?” But they made me senior scholar already so it didn’t really matter. So why I wanted to be a film critic – I didn’t really know why I had this curious notion. But having said I wanted to be, I had to live up to it. So, I’d obviously joined the Film Society and did all this university journalism…

CD: Was that when you started seeing art films – when you joined the Film Society? Or had you seen…

PH: A few. But during the war there were no imported films, not European films. But George Hoellering had already started the Academy. I hope you understand the full significance of George Hoellering and the Curzon because I think the film Lindsay goes on about, Letter of No Return, we’d all seen that, for instance. But when was that – 46? I went up to Oxford in 45, so I wouldn’t have seen it. Probably hadn’t seen many art films, because how would you? My idea of cinema was Hitchcock, Welles, Powell and Pressburger… who else? I suppose Lean and Reed.

But it was the age when absolutely everyone went to the cinema. More cinema tickets were sold in 46 than before or since. I think a lot of people went to films just because there was nothing else to do. But also there was a lot of real interest, actually. There was a very lively Film Society movement. They really annoyed the Institute. I remember Denis [Forman, the BFI director] being furious at these Film Society people. A woman called Mrs Hancock who drove him mad. But they were very active.

There were the art cinemas – several. There was Monty Manvell’s book Film, which we’d all read: it was the only book we could afford because it only cost sixpence or something. There was Penguin Film Review, which was a dreary little thing, but there it was. I think the critics probably counted for more then than now – what were known as the Sunday ladies: Dilys Powell and Caroline Lejeune. It was more of an interest, you know? I think Sequence came at a moment when people were looking for that kind of thing. People had an illusion that it came into a kind of wasteland: not at all. There was a very lively atmosphere around.

GNS: It was that sort of [Ernest] Lindgren, [Roger] Manvell film culture which was strong on promoting classics on the screen…

PH: Hmm.

CD: …but at the same time Lindsay, Gavin and yourself represented a new generation compared to, for example, Lindgren or Manvell.

PH: Oh, yes of course, naturally. Geoffrey, Lindgren and Manvell and old [Paul] Rotha were sort of orthodox. And then there was the sort of – I mean there were some very good film critics writing in the press: George Stonier, Dilys Powell, Richard Winnington. Lots of good people. But the point about Sequence was that it was very young. It was very dogmatic and opinionated. It was very enthusiastic. It loved westerns as long as Ford directed them. It loved musicals as long as MGM produced them.

There was this key sentence which is held to define Sequence – I’d forgotten how much Lindsay disliked Powell and Pressburger, but it’s this: “If you like Letter of No Return you can’t like Black Narcissus. You can like King Kong but you can’t like Black Narcissus. If you like Black Narcissus you can’t like Letter of No Return – if you think you enjoyed them both, you’re wrong.” And that’s what he liked in Sequence.

But what Lindsay really attacked was sort of middlebrow. You could have high art, you could have entertainment, but it had all that stuff in the middle, and he felt that people like Powell and Pressburger were sort of… I don’t agree. I think A Matter of Life and Death is rather good, Colonel Blimp even better, but Lindsay thought that they pandered to this middle class taste, which he didn’t like.

Does that clear up Sequence?

2. Taking over Sight & Sound

CD: I’d like to know the circumstances of your move to Sight & Sound.

PH: Well, I don’t really actually remember much. Obviously Denis was appointed [BFI] director, and then his first idea was to launch the magazine properly and he appointed Gavin [Lambert]. It’s a surprise in a way that he didn’t go for Lindsay. Maybe Lindsay didn’t want it. Certainly Lindsay would have been too much of a handful, but anyhow, Gavin was appointed.

Obviously, Gavin couldn’t do it all alone. I can’t remember if they asked me: “Would you like a job?”, or if they advertised it and said: “You might as well apply.” I think they just offered it to me. I remember going to some sort of interview with Denis, and then taking a salary cut. I thought I was raving mad. I thought: “Oh well, you can do a couple of years and if it doesn’t work out you can back to a nice respectable academic life.”

CD: So why did you decide to take that salary cut?

PH: Well, the salaries were both so horrible, it was probably only a cut of £20 a year or something, but even so… Well, by that time I did want to write about movies more than being a don. I think Oxford put me off rather. So, yes, I did want to do it. But as I say, I just can’t remember how it actually happened.

CD: Could you tell us about the transformation of Sight & Sound, as initiated by Denis? Because you invented it, in a way, with Gavin.

PH: Denis quite rightly thought the magazine was an important thing to have. [It had been] this terribly dreary little magazine which I think only went to members of the BFI. Denis wanted Sight & Sound to have a newsstand circulation, which was a bit easier said than done because newsstands don’t want little magazines – they hate them. it was easier then than now, but it wasn’t easy. I think circulation when Gavin left was 10,000, perhaps 11,000. We got it up to 32-33,000, but my God it was hard work.

The transformation was simply having us there. I don’t know what the spirit of Sequence was exactly, but we were running a completely different kind of magazine.

Penelope Houston and Gavin Lambert working on the Autumn 1960 issue of Sight & Sound

GNS: Was there an old guard who had to clear their desks and grumpily leave the building?

PH: There were a lot of old ladies – old secretaries for people that Denis got rid of. But by the time I got there this man Stevenson who was a Sight & Sound fellow – he’d already gone. Of course, obviously. And the famous drunken [BFI] director had gone – what was his name? The man who was always drunk by lunchtime.

CD: Oliver Bell.

PH: Hmm.

CD: When you joined the BFI and Sight & Sound, how much did you know about the BFI or about Sight & Sound?

PH: I actually wrote an article for Sight & Sound before I joined it. Because I was trying to write for all sorts – anywhere that would publish anything. I did an interview with Robert Flaherty – not a very likely subject. But the old BFI was dreadful!

CD: In what way?

PH: Boring.

GNS: I think Denis’s memoirs say that there was somebody who had gone around in a fascist uniform?

PH: Oh really? Well, dear old Ivor Montagu always used to say that the BFI was fascist in the 30s. But he never said why. I wonder who this was?

GNS: I think it’s one of those tales that can’t be substantiated. But it crops up. He probably sniffed the ideological air, didn’t he?

PH: When I was writing my archive book [Keepers of the Frame, 1994], I put in a sentence I was rather pleased with: “The Institute was born middle-aged and only discovered its lost youth when Denis became director.” And I think that summed it up for me. They had this passion for committees. Everything was meetings and committees. And then they got very cross because the committees got independent and wanted to go their own way; it went on and on like that. Terrible, dreary place. So Denis was absolutely marvellous – as everybody knows. Wonderful person to work for. The whole thing was enormous fun.

I remember once I was entertaining a Sri Lankan director. The only Sri Lankan director who wasn’t Sri Lankan, who was something like Portuguese, and in the next door office Lindsay and Derek Proust were having a row, which eventually got to Annie Get Your Gun proportions, with each yelling: “I can shout louder than you can.” And there was this fearful racket and I sort of apologised to this man who I was trying to be polite to. I said: “I’m terribly sorry. It isn’t usually like this.” And he said: “Do not apologise. It’s so stimulating.”

And I think that that was rather what people felt. We were all very young; we were all very responsible; we were having a hell of a good time; and we were producing quite a lively magazine. The Institute in those days was absolutely tiny: when you knock off the secretaries and the few people who were doing the administration and so on, there can’t have been more than a dozen of us, if that. And you were let in on everything.

I remember [Eric von] Stroheim coming. We all sat at the boardroom meeting and he talked, and afterwards he sent some sort of thank you note to the BFI. He wrote: “Special greetings to the young lady with the infantry-pants blue eyes.” And they held a sort of identity parade, and decided it was me because nobody else had blue eyes, and nobody else [outside Sight & Sound] could you call by any standards young. And I thought: “Whoa!” This is better than the war ministry, isn’t it? But I was 22 or 23 by that time – that is pretty young, isn’t it?

3. Running the magazine

CD: Could you tell us about the day-to-day work in the Sight & Sound office with Gavin in the early 50s? How did you divide work? Was it only the two of you?

PH: The two of us and a secretary. That was it. That was always it, really.

CD: Did you have different roles?

PH: I was more in charge of the [Monthly Film] Bulletin and he was more in charge of Sight & Sound but it overlapped all the time. The Bulletin was a very casual affair in those days. We only had the main credits, so we didn’t have to do all that credit searching. And there were a great number of terrible little westerns, the sort where the scenery falls down, and little thrillers and awful three Stooges comedies – all just made to be the lower half of the double bill.

And I think we paid [reviewers] 50 pence – 10 and 6 – and it might have been a 10 and sixpenny book token – not even money. And to get people to sit through this rubbish for this paltry sum was – I mean most of the time with the Bulletin it was just bullying people and saying: “Go along and see the wretched thing,” you know. “And you won’t have to see another for two weeks…”

We used to have to do lists of shorts and I remember finding Daphne Hunted, my secretary at the time, in tears because she was having to type out all these titles, one of which was Nit-witty Kitty. The things one remembers! And she said: “I can’t bear it. I simply can’t spend the day typing out Nit-witty Kitty.”

We did take a very casual attitude to the Bulletin but it got produced and of course the awful little films had one-line reviews.

CD: Where did you find your reviewers?

PH: I think we bullied anyone around. They were no good – they weren’t fit to review anything, a lot of the people we used. The serious films got properly reviewed. There were a few odd people. I think Jeff Bernard reviewed a few, who was then working on a building site in Soho. I know he reviewed something by [Terence] Rattigan. Rattigan rang Gavin to complain – this must have been a signed review – and said it was an outrageous review. Rattigan stuttered slightly and he said – this awful review – “And what is more I understand it was written by a n-n-navvy,” which was Mr Bernard.

But you know, people like that; there were people hanging around Soho who would do anything pretty well for 10/6, and secretaries at the BFI and so on. None of them were fit to review anything but it didn’t matter because they didn’t have to. They just had to be there. I shouldn’t be saying all this, should I? It’s rather irresponsible.

GNS: What about people who…

PH: The serious films we did take seriously, I must say, in the Bulletin.

CD: So who would you ask to write them?

PH: Well, there were just other people around. We did a lot ourselves. Some of them were down under pseudonyms, I’ve no doubt. Well, you know, people around. You’ll have to look at – did we sign them there? I think we signed the main reviews and not the little short films.

GNS: You had initials.

CD: Which is a big problem now at the BFI because when someone wants to find out who wrote a review – it’s impossible to know.

PH: Well, some of them you could guess. Basically they were written by quite a small group of people. Karel would have written some, Lindsay, obviously, Gavin, me and who else? I can’t remember.

CD: You had Robert Vas, you had Alain Tanner… all these Europeans who didn’t speak very good English who wrote important articles and reviews in the 50s.

PH: Yes, Alain used to answer the information department phone and say: “Informations, informations.” And people like Mary Beckwith got very cross at this and said: “It’s improper. He shouldn’t say ‘informations’.”

Well, day-to-day work: you know, producing a magazine is what you’re doing. You talk about it, you plan articles, you think about things. [Laughs] Think about things.

I remember around that time we had one of these ministry people come round – they were doing time-and-motion studies. He was a very sensible man. He said: “I don’t think I need bother to spend much time with you people because obviously you’re thinking all the time.” And we said: “Well, not quite all the time.” And he said: “You must be thinking most of the time. So, I’m not going to bother to clock your movements.” Yes, we were rushing in and out to films, and getting ideas about writers to use: just everything you do.

CD: Talk us through the Blue Lamp affair.

PH: The Blue Lamp affair. Gavin was very stupid, because he wrote this highly critical review of the Blue Lamp, which centred entirely on the scene with Gladys Henson, the widow of the newly dead Dixon of Dock Green. When they come to tell her that her husband is dead, she’s putting flowers in water and they say, you know: “He’s been shot,” and so on. And she says: “I must just finish putting these flowers in water,” or some such.

Some people thought that this was a British stiff upper lip, and realism and all that. And Gavin thought it was absolutely ridiculous – rightly so. And he wrote a very critical review.

The stupid thing was that we did sometimes use pseudonyms because otherwise it appeared that we were writing too much in the paper. So, we’d already got two or three things in our own name. If you ever come across the name John Morgan in Sight & Sound, that’s a pseudonym. It was such a boring name. And Gavin thought that nobody would think it was a pseudonym because it was such a dull sort of name. But I think he signed this review.

And Balcon was absolutely furious. The good thing about Balcon was that he really did care about movies. He was really hurt by a criticism of an Ealing film. So Henry French was approached by Balcon to rig the whole thing up. There’s a very funny pile of correspondence in the boardroom papers in the BFI Library about it.

Now the Chairman back then was Cecil King – who was the Daily Mirror, you know: he simply was Mr Daily Mirror or Lord Daily Mirror. He said: “Do you want to sack Lambert? Is that what you really want?” And they said: “Not really, we just want to give him a really good kicking, we don’t actually want to sack him.” I think they wanted an editorial on the bugle, God knows what. And King apparently said: “Well, you either sack him or you let him get on with the job. You either trust the editor or you don’t. You can’t mess him around, tie him up in chains and expect him to do the job properly.” And so Cecil King won the day for Gavin. So that’s secondhand from Denis, that’s the Blue Lamp story.

CD: And so Gavin left.

PH: Yes, first to shoot the film in Morocco [Another Sky, 1955]. I can’t quite remember what happened then. I was obviously in charge. And then he left for good. Following in the wake of Nick Ray.

4. Becoming Editor

CD: And you were the obvious choice for the BFI to succeed him?

PH: Well, the Institute was so charming, always. I took over as Acting Editor. They made it absolutely, crystal clear that they’d been searching high and low for someone else and they were stuck with me. Left you feeling very confident at the start, taking on a job like that.

GNS: So you then step up to being the Editor of Sight & Sound. You bring in an assistant who does what you were doing.

PH: Roughly yeah. The Editor was in charge of Sight & Sound, and the number-two in charge of the Bulletin with a lot of Sight & Sound responsibility as well – roughly. You have a whole list here of people who worked for me, including one I’ve never heard of, somebody called Mark Wilcox.

CD: The chronology of who came first in the 50s is a little confusing. There seem to be quite a few in the space of two or three years: John Gillett, David Robinson, Kenneth Cavandagh, Peter John Dyer, and then Tom [Milne]. All in the space of maybe six years.

PH: Well, let’s see. This Wilcox person I know nothing of.

CD: Okay.

PH: I think you invented him.

CD: Then I’ve got John Gillett.

PH: John Gillett. I can’t remember working with John Gillett. I suppose I must have. It must have been very brief. It would have been an absolute disaster.

CD: Why?

PH: Well, John had many virtues, but he would never have been quick or positive, decisive enough. And he wasn’t a good enough writer to be trusted to edit other people. If I did work with him, I think it would have lasted weeks. It would have been an absolute catastrophe.

David was absolutely marvellous. A delight to work with. People underestimate David, he’s so quiet and unassuming. He’s done all those different jobs – editing and writing, running a film festival – and he’s done absolutely everything well, I think. I can’t remember how long it lasted – when he left it certainly wasn’t my idea.

GNS: Were any of the others? Gavin?

PH: Gavin was…

GNS: Very talented.

PH: I always felt that if you fell down at his feet, in a faint or something, he’d simply walk over you. Clever. But I was never terribly attached to Gavin. We had a lot of fun, we had a sort of very good working relationship. I liked him enough – but as you say, David, much nicer.

CD: Then he was replaced by Kenneth Cavandagh.

PH: Kenneth Cavandagh I think was the best of a dull lot of people who applied for the job. He was quite bright. Simply not very interested in films and we both realised it was the wrong job for him. He was more interested in theatre, really. Sadly, just a mistake.

Peter John was a more complicated mistake. He was a sort of Films and Filming [a magazine published between 1954 and 1990] person who strayed into Sight & Sound. He was enthusiastic. He worked hard. He was always at his depth. A bit out of his depth.

I suppose I can tell you this; they’re all dead. There was the awful case when he was caught in barefaced plagiarism. And this is a mark of intense insecurity in a writer because I think it takes just as long to steal other people’s words as to write your own. You can never trust a writer who’s done that, ’cos, well, they were caught that time – how many other times? You’re sitting all the time on a time-bomb. I think that finished Peter, actually. He sort of retired.

Then, of course, Tom who was absolutely wonderful. I had the good luck to work with three absolutely superb people. I don’t think I would have stuck it out without them. Tom was full of ideas, very creative, a very good writer, a very good editor and a very good everything.

David Wilson was excellent, very conscientious, very nice, very easy to work with – just without the sort of flair of Tom and David and Johnny Pym. I wouldn’t want to run down David Wilson but he simply wasn’t on that level. It’s a rather nasty thing to say but I think one has to say it. But he was very good; nothing against David. And John was also marvellous.

Tom was the best writer of the three, perhaps? The most original critic of the three, but they were all very good, very nice people to work with, great friends and full of ideas. They contributed massively to the magazine.

5. Peers, rivals, cross-currents and celebrity contributors

CD: One of my questions is about the relationship between Sight & Sound and other magazines, particularly Cahiers du Cinema. Of course it started a revolution as well in the 50s. Was there any connection between the two, direct or indirect?

PH: We read it, of course, and we admired André Bazin very much. We admired Cahiers very much. We were envious: they’d got Langlois and the Cinematheque and we’d got Ernest and the art crowd, which was quite a difference. I don’t think we actually met them; I don’t think they would have come to London. I didn’t go to the Cannes festival until 1960, I think. And that’s the only place one would have met people. I don’t know if Gavin ever did – probably not.

GNS: Gavin wrote for Cahiers quite a lot…

PH: Did he?

GNS: He wrote a regular column from London in the mid-50s – Letters from London.

PH: I didn’t remember that. Well, he must have had the contact. I didn’t realise.

GNS: Somewhere in Cahiers is a small reference to you by Chabrol.

PH: Ooh. I’d love to know what reference from Chabrol. I love Chabrol. But later on there was all this rather artificial kind of rivalry between Cahiers and Sight & Sound – but I didn’t know that about Gavin. If I ever did know, I’ve completely forgotten.

CD: What do you remember about the Free Cinema adventure? Which in a way Sight & Sound contributed to by writing several articles. Did you see it as a natural continuation of the work that you’d all been doing as critics since the late 40s?

PH: I don’t think so. I think one thought it was the continuation of the filming that Lindsay had been doing since the late 40s. [Laughs.] It was very much a Lindsay thing. As with everything he did, he tended to dominate it.

CD: How significant do you think it was?

PH: Well, not terribly, in the great scheme of things. But at the time, yes, it seemed significant, certainly.

CD: A year after the first Free Cinema screening you wrote an article about another event, the Captive Cinema.

PH: It’s awful to be reminded about articles. What was it about?

CD: It was about the programme of ITV documentaries where you argued that television and television documentaries were more relevant in a way than Free Cinema.

PH: Did I really?

CD: Because they affected more people because…

PH: That seems a very babyish argument.

CD: No, I think it was quite a well-made argument, actually.

PH: I don’t remember this at all. The thing is I really did write a lot of articles and I’ve forgotten most of them. Free Cinema created a lot of stir. We had that very tiresome Lorenza Mazzetti in and out of our office. Day in, day out. One would hide under the table when she came in.

CD: But of course, almost every member of the Free Cinema movement would write in Sight & Sound at some point. Walter Lassally wrote quite a lot of articles; Lindsay, Karel, Tony Richardson… They all did.

PH: Well, they – we – were all seeing each other all the time. And they went in and out. And yes, there was the feeling that things were happening in British Cinema. And yes, Free Cinema was symbolic of it and then it went on to the features.

CD: So what would you say Sight & Sound’s official position on the British New Wave was? Did it support Free Cinema in any way?

PH: Of course it did. Sight & Sound supported the British New Wave unequivocally – for quite some long time. Sight & Sound might have thought that it would rather, at that point, been Cahiers, with its directness of support, but we supported what we had to the hilt. And supporting to the hilt meant writing a lot about; finding the most sympathetic critic you could find; banishing any reservations, or most reservations. If you needed a justification for this you could say: “Well, the films may not be that marvellous but they’re a damn sight better than what came before them.”

There came a point, and I can’t exactly say when the point came, when one sort of starts saying: “Well, they can’t go on having preferential treatment forever”. Say somebody reviewed a film and they were not quite so nice about it – they were not nasty about it but not quite so nice.

I remember I had a letter – I wish I’d kept these letters, I kept them for ages and then they got lost – from Tony Richardson after, I suppose, Look Back in Anger, saying: “How marvellous it is to know that the magazine fully understands and sympathises with and supports in every way what we’re doing and it’s absolutely marvellous. And we’re all forward together.” And then a few years later I had a letter from Tony Richardson saying: “The magazine has never understood the first thing about what we’re doing and it’s absolutely outrageous that this – oh, we’re getting no support from you” and so on, and so on. This was the difference between the all-out favourable review and the less favourable review, five or six years later.

CD: But the British New Wave didn’t last much longer anyway.

PH: No, and Cahiers produced all those top-line directors and we had, what, two minor ones and I like to call Lindsay borderline-major. I wouldn’t call him a major filmmaker myself. I think he could have been but I think he just didn’t do enough. And I think Karel and Tony were definitely minor. I mean became minor whereas Cahiers had six majors.

On the other hand, on the great Satyajit Ray / Nick Ray debate I think we were right. I think Ray [Satyajit] has lasted longer than Ray. You know, Cahiers couldn’t get that kind of people at all. We did get Nick Ray, but when Cahiers got on to the thousand beauties of Party Girl…

I think French and English critical traditions are really quite different. I think we’re more phlegmatic; probably more literary – literary-influenced. I sometimes felt that the Cahiers critics sort of floated above the surface of the film. They’re not reviewing the film exactly – more the film they would like the director to have made. Sometimes you’d read a review in Cahiers and wonder: “What did he really think about that?” And of course we always had the feeling that if they understood English better they might have had some reservations about things they like very much – such as Nick Ray.

CD: How quickly did you pick up on the nouvelle vague, and how revolutionary was it for you and Sight & Sound?

PH: As quickly as we could and revolutionary, yes. We’ve jumped backwards, haven’t we, from the British New Wave? I think most of the films came to London pretty quickly; otherwise we used to see them at festivals.

And yes, it was tremendously exciting. The 60s and a bit of the 70s was certainly the best period to be editing Sight & Sound, because it really was a tremendous time for art cinema, wasn’t it? You had at least half a dozen top people in France, half a dozen more in Italy, the East European cinema, the discoveries we were making from Japan, Bergman… everything happened at once, Hollywood was going through a rather flat patch, and if you were interested in cinema at that time, that was the cinema you were interested in.

For a magazine it was wonderful. The amount to write about was enormous. It was exciting. When there was a new film like Bergman’s Persona or something, you’d probably get six articles coming in trying to explain the film. That’s the kind of readership you had. I don’t think that happens nowadays.

God, Persona – whoo. The sort of things one did. I met Susan Sontag through Richard Brown and she reviewed Persona for us. And I remember on a hot, hot, hot summer weekend having to go to Heathrow to pick up Susan’s review because she was passing through Heathrow. And she had to be sort of escorted by some sort of police person from one airline to another – I mean, the devotion we showed in those years. My God, who’d do it now? I had a 30-mile drive to get the copy, it was Sunday and I was streaming with sweat. And we bothered because it was Susan’s Persona. That was a real coup – Susan Sontag writing.

And earlier it was a bit of a coup to get Tynan writing – ’cos I’d known Tynan quite well at Oxford. This was one way how magazines were. He wrote these very good articles for us – the Garbo article and more. And then he said: “I’m sorry, I’m too expensive for you now.” All he’d wanted was to publish articles that made his name – which they did, along with all his other stuff. And he said: “Sorry but that’s the end of it. You can’t afford me,” which we couldn’t.

CD: You also asked quite a number of other film personalities who were not writers, like actors or filmmakers, to write for Sight & Sound?

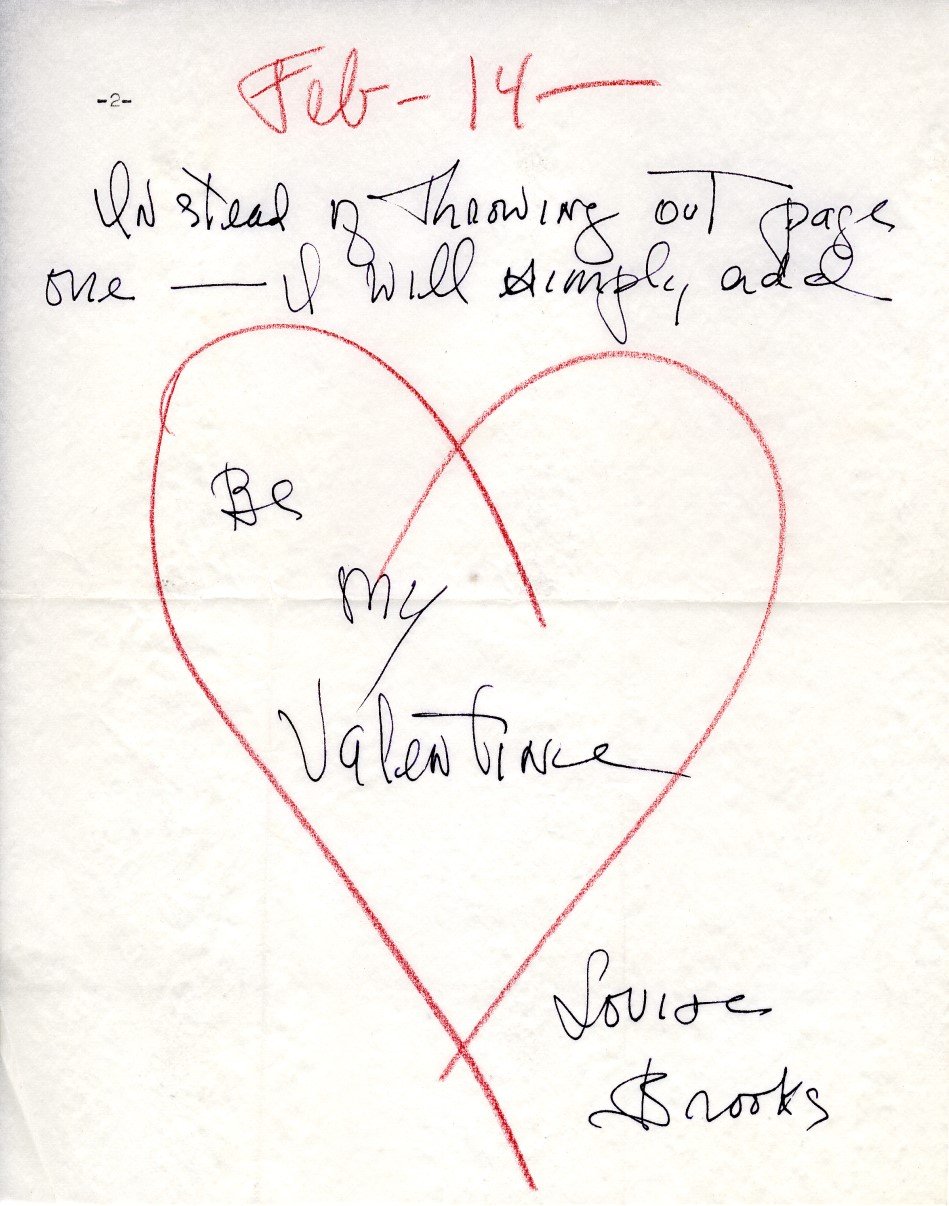

PH: Well, yes. Sometimes they just turned up and suggested it; we didn’t always ask them. Sometimes we did – like Louise Brooks.

CD: Could you tell us about it? How you met her?

PH: We never met her. This was the extraordinary thing, and this shows the magazine did have quite a bit of influence. She settled in Rochester, New York, which was home of the Eastman House Archive – the Kodak Archive. And the curator of the Archive was an old chap called James Card, whom I never actually met, ’cos I don’t think he travelled much. She was doing her research at Eastman House for articles and I think she said to him: “Who should I approach?” And he didn’t name any of the American magazines, he said us. That’s how we got her.

Editorial advice to Sight & Sound from Louise Brooks

We got a lot of things like that. People would go to us first, because the magazine did carry that extra bit of weight. I remember being told by some American in, I suppose, the 60s: if Sight & Sound very strongly supported a European film, an American distributor would take it up. They wouldn’t do it if an American magazine supported it. I don’t think it was true, but it’s what I was told. Which meant one felt one had some influence – used for the wrong purposes, no doubt.

GNS: What were your relations with the American magazines – Film Quarterly and Film Comment and…

PH: One met the editors and people occasionally. But the Americans were never much seen in Europe – I mean, they didn’t come to Cannes until the 70s. We wrote letters, we saw them, but they weren’t close contacts.

CD: In the early 60s a number of other small British film magazines emerged – some of them not always very nice about Sight & Sound, to say the least. How did you and the magazine react? Did you think they had a point at all?

PH: Honestly, I can’t remember these things. Obviously Sight & Sound was the establishment magazine. It was there to be shot at, and it was shot at. You mention two of these articles here. I can’t remember either of them. I suppose one’s reaction might well have been: “Oh, there they go again,” you know. Or it might have been: “Yes, well, they’ve got some very good arguments against us there,” I don’t know. Small-scale, critical skirmishes of 40-odd years ago. I don’t think anybody wants to know about them now – I don’t. Or would you like to know? I can’t remember anything.

One thing we did do, later on, was I pushed the Institute into starting this little fund to back – to help back – other magazines, including Movie, who were one of our main critics, I think. And Film Dope. There was always a committee and very little money. But I did think well at least we can do something, you know? So we weren’t fighting the other magazines.

GNS: I think you said at one point that the sums that were made available were just enough to prolong their death throes.

PH: Well, we did. Yes, I think I said that probably to whoever was director at the time, that we must give them more money. I’m sure I did. It was an effort. At least one persuaded them to do that much.

6. Small-screen criticism, sales and advertising

CD: The BFI officially changed its official remit to incorporate television in 1960 or 61. But as early as the mid-50s there was a regular page in Sight & Sound called Television, usually written by David Robinson…

PH: I think – I’m sure we were told to do it. I never wanted television in the magazine, I must say, ever. I would have wanted some television, I mean I think there’s a huge overlap area of films made for television, which you had wanted to write about. Films like Caught on a Train, that early Stephen Poliakoff. You certainly wrote about wherever it was screened. But it seems to me that film people are not that keen on television. And television people certainly wouldn’t buy a film magazine with one article a quarter. And I thought it was silly to have it in the magazine, but we were stuck with it and that was that. After Contrast of course.

Contrast was an interesting experiment. There were various governors who were television people. There was this feeling that television would benefit from a sort of television Sight & Sound. The BBC, certainly, and I think ITV put up a very small amount to launch the magazine. The first editor was Peter Black, the television critic of the Daily Mail, who was an excellent choice, a very intelligent person – the Daily Mail should not be held against him. He was one of the few TV critics who were not just using television to write a sort of smart-aleck column; he was very serious about it. He’d popularise and [do it well].

Unfortunately, though he was a very good journalist, he wasn’t such a good editor. I don’t think he enjoyed editing that much. And he couldn’t stick the BFI. He found the bureaucracy and the committees and all the fuss very comic and absolutely ridiculous, but rather tiresome at the same time. There was some sort of editorial committee for Contrast – John Huntley was on it. For some reason – Peter was a very polite man, so I’m not sure – he always used to call him Lumley. And Huntley was always late, ’cos he was always late for everything, and Peter would say: “I really don’t think we should start without Lumley. Where’s Lumley today? I think we must wait for Lumley.” And I think it all got him down and he quit.

And then of course David took over, and he was also a very good choice. And I think Contrast was coming along quite nicely. But the money ran out and that was that. The trouble with the Institute is that they never would spend any money. They never had any money. The life of the Institute was struggling from one financial crisis to another, but they never had any sense on how to spend money. They never put any money into Contrast. They just packed it up.

They wouldn’t sell anything properly. The Production Board films were never promoted until Tony [Smith] got in Carole Myer, who did a wonderful job. But until then they weren’t even selling them at all. At one point we had Christmas calendars, with film stills for every month. You only do that to make money, of course. Would you believe, the Institute actually managed to lose money on the Christmas calendars. Absolutely hopeless.

And it affected me very much on the magazine. Hopeless, awful saga of incompetence and the horror in selling it, for years. I had a cracking good unit work for me – under me. Three people. They were extremely enthusiastic. I told you we got the circulation up to over 30,000, which was extraordinary. And a lot of that was the BFI membership. And that’s very crucial that we kept this sort of lifeline, of having the membership to sell this sort of magazine. You know, you’re selling a dozen copies here and a dozen there, in small shops. It’s very hard work to build up a circulation but we had this awfully good team who were really keen, really enthusiastic, and the circulation just went up and up and up, year in, year out. And then the person who ran it retired; somebody left for good, and it was taken away from me by the Membership Department, who didn’t give a damn about it, of course.

Then there was an absolute horror period when I kept saying: “What is going wrong?” And it turned out that the person who was taking orders was sort of useless – actually so useless that he couldn’t cope at all and he was stuffing orders into the drawers of his desk unopened. Eventually, about a year of orders – with the cheques – were discovered and he was got rid of. But it did terrible damage to the magazine’s circulation.

The wonderful Institute then appointed a man who was quite efficient. What he was efficient at was stealing the stuff. Literally: anything that came in that he could pinch, he pinched. They took quite a long time to catch up to him, too. I just gave up. The circulation started going down – further and further down. Nothing you can do about it. The only way to have got it right was to say: “I must have a department working to me that will do it properly.”

We ended sharing a sort of sales person with BFI Publishing – the books department. She was a book person. She didn’t know or care about magazines, which are quite different. I had to bully her to get her to do anything. She was quite nice, actually. But what could you do? You could go over and talk to them until you were blue in the face and they just went on with these inefficient systems.

There was a whole sequence of these horror stories. You wouldn’t believe that you had two people [who were supposed to be] running but were actually destroying your order system.

But the decline happened anyway, because a lot of little bookshops which would take two dozen, one dozen copies – and a small magazine needs that kind of thing. You don’t get sales by dealing with WH Smith – well, you do – but most orders came through [smaller vendors]. And gradually these little bookshops packed up. There were a lot of them abroad, of course. A lot in France, out in Germany; America; Canada. And I think that the little bookshop was a dying thing. The expense of filling the order became more than the problem. They never made any profit; they just did these things, these sort of shops, but when they came to actually making a loss I think they had to stop. I don’t know how they’re doing now with the magazine. It’s not easy. Never was.

CD: But back in the early days when you were still in control of the marketing, did you and your assistants even deal with negotiating pages of adverts for the magazine? I mean, did you really do everything?

PH: I didn’t do the ads, no; the person who was in charge did that at all times. I made suggestions; about the time I left I was saying: “Why on earth can’t we get video?” and so on. I think it was perhaps a bit too soon. Now the magazine is packed with video ads, isn’t it?

CD: Do you think Sight & Sound was better off within the BFI, or could it have very well operated separately?

PH: Well, it couldn’t have existed without the BFI. Can you see any government or politicians in any country saying: “Let’s subsidise a rather specialised quarterly film magazine”? No.

7. The return of Lindsay Anderson and “a monumental row”

CD: In the late 60s Lindsay Anderson became a BFI governor. And that triggered a bit of a crisis between Sight & Sound and himself.

PH: [Laughs] Do you want to hear about the famous meeting? To begin with, Lindsay and I had not spoken to each other for the best part of – oh, a long time.

We fell out in the most absurd way, to start with. God, do you really want all this? I suppose you do.

Lindsay had covered the Cannes festival for us. For several years. I decided that Cannes was really so important that it had to be done by the magazine, not by a contributor. And I knew that Lindsay would make a bit of a fuss so I kept putting off saying this but eventually got round to it and there was this monumental row. I mean I thought he’d be a bit cross. But I knew he could still go to Cannes – he had all the contacts and everything. He raised the roof. Screaming and shouting – the whole Lindsay works. I don’t know if he really thought people would back down when he yelled at them. So that started the row.

Then I think we had another. As I said, when I took over Sight & Sound the Institute had shown no particular desire to give me the job. I was what? Twenty-eight. So I wasn’t that confident. It was very good to have Lindsay as a helper and an adviser and a friend and all that, which he of course was. It was nice to feel you could always go to him and say: “Am I being a fool if I do this?” and so on.

The trouble with Lindsay is that he always wanted to dominate. I don’t think he was any good at equal relationships and they’re not there in the films either. This would have been a minor factor but I annoyed him very much writing about If…. I wrote: “There’s a missing generation in this film and it’s behind the camera. Because the parents in it were not parents, they’re grandparents. They’re these authority figures,” and he was furious about that.

I actually remember saying to him at one point: “I’ll probably agree with you about 75 per cent of the time – you’ve got to allow me the other 25.” He would never do that. Never. So, after the Cannes festival row, by this time I was getting a bit more independent-minded and I think we had various minor rows, didn’t speak for a while.

Then along comes This Sporting Life – and this was typical Lindsay. He wanted it on the cover, of course. We did too. He turns up in the office and we say: “We’ll get the stills in the usual way from the PR people.” He said: “No, no.” He turns up with two stills: both very nice but all wrong for covers. And I said: “Sorry, Lindsay, we must have some more to choose from.” He was furious, of course. Eventually produced some more. I wasn’t happy with the one we used. We could never get him to give us enough to choose from.

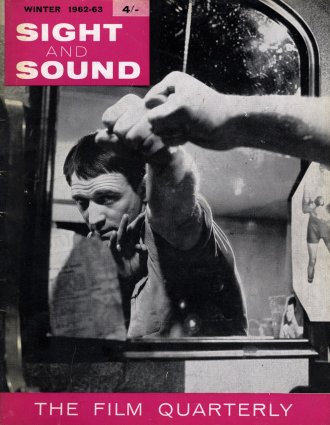

GNS: It’s the big one of Richard Harris?

PH: Er, yes. With a sort of fist up, and a mirror, I think. It wasn’t very good. There was a certain amount of friction there. Very gradually we sort of didn’t speak to each other. So, Lindsay becomes a governor, with Karel, as always, in tow, for I think of the sole purpose of getting me out of the magazine. He resigned right after this famous meeting. I was surprised, because whatever else, we talked the same language, which a lot of the governors did not. And there was Lindsay, the great anti-establishment man. Instead of coming to me and saying: “This is what I don’t like about the magazine, why don’t you do [this or that]?”, so we could have talked, perhaps understood things – instead the anti-establishment man took the establishment route.

Well, the meeting. What I think happened was that Lindsay and Karel made such a song and dance that the other governors got pretty annoyed. I think [John? William?] Coldstream and [Stanley] Reed thought: “Well, let’s give them this meeting. Let’s let them have it all out, say what they want to say and then let’s get shot of it and they won’t be able to come back to it.”

Now I got on very well with Stanley. I liked Coldstream. Would they have thrown me to the wolves? I don’t know. They might have hoped that it wouldn’t come to all that, or they might have been determined to make sure that it didn’t come to that. I really don’t know. It felt like as though I was being thrown at the meal that evening.

The famous meeting happened in a little Italian restaurant in Greek Street in the evening. They produced some sort of supper. Most of the governors turned up – most of them, I think. But it must have been during the World Cup, 1970. Several made it quite clear that they wanted to be off as soon as possible to watch the football.

GNS: A new insight into BFI governors!

PH: [Laughs] Well, Lindsay had promised to circulate a paper before the meeting. But being Lindsay of course, he never did. He turned up with some scrappy piece of paper.

I never really understood just what he’d got against us. I mean, obviously he felt we weren’t backing British films the right way; but this is very hard to prove or demonstrate. They would say: “You don’t have enough articles on British cinema.” And we’d say: “We’ve run all these [articles] in the last year: what are you talking about?” It’s very hard, with a dozen or so people around a table eating bits of cold pasta and wanting to watch the World Cup, to get them to understand the niceties of all this.

The meeting turned into a sort of niggling and nagging and never getting anywhere really. Lots of stupid little complaints, round and round in circles. I got more and more fed up with the whole thing.

I remember this one beautiful moment, rather typical of the tone of the meeting. Carl Foreman, who was a governor, and actually an old friend, said he “couldn’t understand why Sight & Sound was always going on and on about Buñuel. Obviously, Buñuel was rather important in his day back with L’Age d’Or and all that. But why?” Carl had just produced a picture called Mackenna’s Gold which was meant to be a classy western but made no money and attracted no good reviews. By this time I’d thrown caution to the wind and said exactly this: “I haven’t had much to enjoy at this meeting, in fact nothing, but you’ve given me one thing to enjoy very much, and that’s to hear the producer of Mackenna’s Gold patronise the director of Belle de Jour”. [Laughs]. At which there was, from the whole lot I think, a pretty shocked silence.

Carl rang me the next morning with an absolutely abject apology: frightful meeting, the whole thing had been a nightmare, he didn’t know what he’d been saying and hoped I hadn’t been upset by the whole thing… Absolutely extraordinary. But the meeting got nowhere; it wandered round and round in circles.

And the last surreal touch: I went to the ladies, which was occupied, and who comes out but Lindsay. And I laughed a lot at this and of course he was furious all over again.

We were stuck with an editorial committee for a while after this occasion. I can’t remember how long it lasted – not very long.

GNS: If you look at the masthead of Sight & Sound in the 60s you read of an internal editorial committee: Stanley Reed and Ernest Lindgren and people like that. Were they just names?

PH: I don’t think they even met. But after this meeting we had a committee, with a governor.

I took it terribly seriously. I insisted that they read everything – or at least that the chairman read everything. Can’t remember who the hell was the chairman. On a Thursday night I would send out 30,000 words of copy. There’s quite a lot of copy in a 72-page mag.

On Friday morning I would get the expected phone call: “But you’re ruining my weekend!” I said: “Well, I’m awfully sorry but we must have your comments by Monday, or of course the whole schedule will fall apart. And by the way, I’ll be sending you another batch of copy later next week.” And there’d be a scream. “How can you do this to me?”And after a while they sort of said: “We’re not doing it. You’re the one who wants this committee. We don’t need it; we’re fine without it.”

CD: But Tom [Milne] resigned.

PH: I don’t think he resigned because of that. They only sacrifice was that we had to change our designer. That seems odd, but we did. It didn’t much matter; we never had a good designer anyhow. I think Tom just wanted to do something else.

8. BFI management

CD: From the mid-60s you became part of this new structure within the BFI called the Executive. Did you enjoy that role?

PH: One of the good things about working at the BFI, that made it quite an interesting place: you had this extraordinary range of people – distribution people, NFT people, production people, journalists like us, the Archive – all working in very tiny units on quite different things. You wouldn’t normally meet all those people in the course of your daily work. And being on the executive obviously helped [me] to understand what other people were up to. A bit of a spurious democracy. Because the governors made the decisions and the director and the deputy carried them out. It was useful, yes.

It fell apart in the regime of Keith Lucas. He was somebody who simply couldn’t make up his mind. Or maybe didn’t want to. And this was a curious period: not just at the Institute but everywhere, the great word was ‘consultation’. Everybody thought they should be consulted about everything, from junior staff interviewing staff for senior jobs down to the colour of the wallpaper. And as I say, it went countrywide. Well, obviously with the executive, Lucas had this marvellous opportunity to keep consulting and never make up his mind at all. It was a superb delaying tactic.

The job list was a bit of it. Departments were always trying to employ more people, either to do what they were doing a bit better or to do something new. It was decided that these jobs should be listed in order of priority. This was insanity, of course, because we didn’t know about the staffing levels in other departments: if somebody was simply doing some optimistic power-building or if the job was really needed. We had to sit round solemnly, hour after hour, considering whether somebody restoring films in the Archive was more or less important than somebody working for Distribution. Dear oh dear!

Eventually this list came into existence. I think people must have agreed to it because once their job was on the list it kind of ‘existed’ – and eventually, after ten years, it might get to the top of the list. So, what then happens? I think I’ve got this all right: there was a lot of complaint that the Archive service running the van between the two places wasn’t efficient enough. And the Archive say: “We’re doing our best but to run a better service we must have a new van.” So as usual there’s bound to be hours of discussion. Seven, eight people sitting around for ages. Eventually they said: “All right, Archive must have a new van.”

Then a few months past and people say: “Why is that service no better now the Archive has its nice new van?” And the Archive said: “Oh yes, of course we haven’t got a driver for the van,” which is sitting in its garage. So another two hours of discussion, and even people like Colin McArthur can see that this is a bit ridiculous, so the Archive van-driver job, which is probably not on the list or is right at the end of it, leapfrogs all the rest. And this kept on happening. It was an insane way to run an organisation.

And we had these weekly meetings, which would start at 10 or 10.30 and often not end until 4 in the afternoon. What we were talking about, God knows. They were so incredibly boring one just couldn’t listen to them any longer and I used occasionally to read the Sporting Life, which annoyed them much more than reading the Times did, I discovered. It was typical of Lucas’s hopeless weakness that he wouldn’t even have the guts to say: “Put that paper away,” which he should have done.

And Colin McArthur kept going on and on about something called “the crucial issues”. Then we discussed them so much that I never knew what the crucial issues were. It was very easy to tease Colin. I once said to him: “Shouldn’t you be getting some new crucial issues? Aren’t that old lot getting a bit worn out now?” He was so cross. But it was absolutely pointless, the whole thing. And I think everybody was very relieved when the BFI under Tony Smith abandoned that structure and we didn’t have to do that anymore. But before that it worked perfectly well under Reed.

9. Amongst colleagues

GNS: Richard Roud [a critic for Cahiers du Cinema, Sight & Sound and the Guardian, Cinema One author and director of both the London and New York Film Festivals] was someone who had real gifts.

PH: Richard was great. We were colossal friends.

GNS: I think you leant on him intellectually [more] than with other people you had working for you?

PH: I hope I didn’t lean. Well, I certainly couldn’t discuss ideas and things with Peter John, but I did with Tom and David and so on. But yes, Richard did have his French connections. He certainly broadened the magazine out in some ways. Look at the [London Film] Festival when he was running it. It was great.

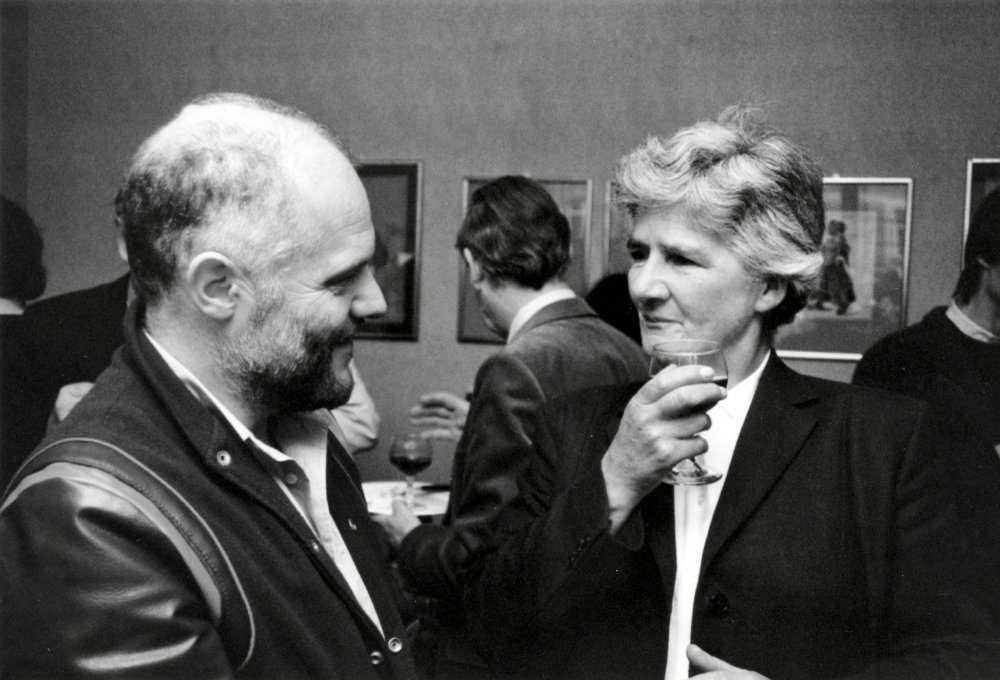

Houston with Richard Roud

CD: How did the programming of the NFT and the LFF evolve once he left? Did you have the same relationship with Ken Wlaschin, for example?

PH: In the earlier days the NFT office was just down the corridor from us. Once the NFT people moved down to the Southbank there was much less contact. I liked Ken, I thought he was very good, but we never had any close contact.

It made a huge difference – by the end the Institute was split up into all these little [activities]: the Production Board in one place; half the Archive in Berkhamsted; the NFT on the Southbank. From what I gather the people like Nick James now have very little contact with the other departments, whereas we had contact all the time.

CD: And do you think that’s the way the BFI should be?

PH: I think it made it a more interesting and attractive place to work because there were all these different people. If you’re having a whole collection of different people in different places they might well be working for different organisations, [disregarding the] infrastructure.

GNS: In the 60s and 70s you could draw on people from all over the Institute to write articles in Sight & Sound. There are still a few, but I think the number dwindled.

PH: Oh, I’m sure it did. You would only work at the Institute if you were mad about films, really, apart from the accountants and those sorts. I mean, somebody like Leslie [Hardcastle] was mad in a quite different way to me, and Richard Roud was different again, and heaven knows Ernest Lindgren was different – but we all, and a lot of others, were united in being crazy about movies. I don’t think that applies any longer, at least not from what I hear.

Likewise the directors of the BFI were all a mix of different things. Denis had been in the army; I suppose you could say James too – his main experience seemed to have been town major of Paris or something. Stanley was a schoolmaster. Lucas came out of advertising. Tony was an academia-plus-television person. I don’t know what Wilf started at. But I get the feeling that now you couldn’t run a place like the BFI unless you’ve done some ghastly arts-administration course. And what first-class person would want to do an arts administration course – actually going to university and learning all that boring stuff?

In the same way, nobody in our day was taught journalism. Heaven forbid! You just went out and did it and tried as far as you could do to learn your trade and get people to publish stuff you wrote, and to write for as many people as would take your stuff. And gradually you found out how to do it. But I don’t think people would put up with that nowadays; you have to go and actually learn it. I must say I prefer our bad old ways.

Even the governing bodies of the BFI were extraordinarily interesting in the early days; a great mix of people, much broader; not this scaling it down. Later it became that the chairman had to be a movie person, but before that, Leslie said that one of the really good ones was something very important in NatWest, or one of the big banks.

10. Education

CD: What was your relationship with fellow members of the Executive such as [Education Officer] Paddy Whannel, for example, in the 60s? And between Sight & Sound and the Education Department?

PH: As little as possible. I liked Paddy but we didn’t have any relationship. Our contacts were with the NFT, and to some extent the Archive. I strongly disapproved of the Education Department and all this media studies lark. Children should be learning Latin, not wasting their time on media studies.

CD: Because you did share one thing, which was the Cinema One series.

PH: Yes, well. I’m terribly proud of Cinema One. I think it was a cracking series.

CD: How did it come about?

PH: Very nice film-mad publisher called James Price. He worked for Secker [and Warburg, the publishing house]. I think I may have read something of his and got him to write for us. Anyhow we cooked up the deal between us. It was the only kind of deal the Institute would have stood for then. We would commission the books and do all the editorial work. Secker and Warburg then published and took all that side of the responsibility.

And of course they also got the profits, if any, because the Institute would never invest. In 1974, it would never put a penny into anything. If I’d gone to Stanley and said: “You know, we want £10,000 or £20,000 or however much to launch a new series of books,” he’d say: “Don’t be silly.” If I went to Stanley and said: “We’d like to launch this series, it’s not going to cost the Institute anything except some of my time, or spare time,” he’d say: “Great, fine. Go ahead.”

It worked out perfectly alright. Some of their books sold jolly well, like Peter Wollen’s Signs and Meaning in the Cinema, and David [Robinson]’s Buster Keaton book. Some were selling, 15,000, 18,000, 20,000 – which is a lot. Not all, by any means.

One thing I insisted on was that every book should have its [edition] number in quite big figure on the spine. Because I thought if people were collecting the books they wouldn’t like to have gaps; even if they weren’t interested in the director or subject, they might buy that book. I don’t know if it worked or not. [Laughs] Basic marketing by the editor. It was a lot of fun too, because it could include a bit of everything. It wasn’t tied to films or directors: you could have a cameraman.

CD: When and why did it stop?

PH: Oh, it sort of changed publishers and the early standard of production was very high and then as things do it kind of petered out. Standards dropped. Secker were very good with it, but James moved somewhere else and took it with him. I can’t remember the exact sequence, but as things do, gradually it just went wrong.

11. Exit from Sight & Sound

CD: Could you talk us through your departure from the BFI, and how the book came about?

PH: A lot of things were changing. I think cinema had become simply less interesting. European cinema was really in retreat and Hollywood was being taken over by the dinosaur film – the films made for 18-year-olds and so on, and I think the magazine certainly had to change. Not the kind of drastic change that actually happened, but [some] change.

I obviously wouldn’t have been the person to change it. It was becoming less interesting to do and, I think, outdated. The assumptions about its readership and so on were becoming or were outdated. I was working in this division headed by Colin MacCabe.

I always thought Colin was a very odd person, who wanted to be all at once an academic, a film producer, a film director, a writer, a publisher, the whole shooting match all at once. And he felt that the BFI would let him do that. He was also slightly barmy. I mean he actually went barmy once. Had to ring his office from Heathrow and say: “What am I doing here?” And sort of collapsed and had to be fetched home and all that. He was the kind of resident intellectual much respected at that time, I suppose, by Wilf. He didn’t like me much; he didn’t like Sight & Sound at all. He couldn’t wait to get his hands on it.

Well, I was 63, and would have had to have resigned by 65. I could have stuck it out and had two years of very acrimonious, bad-tempered relations with Colin, leading nowhere; obviously the more sensible thing was to strike a deal with the BFI, which was actually rather a good deal. I [had] stayed out of inertia, as one does. I’m very glad I left when I did, actually.

With film producer Peter Salisbury

GNS: Did you consider leaving in the 70s?

PH: No.

GNS: Weren’t you offered a newspaper column?

PH: I did The Spectator column for a few years. Great fun it was too.

GNS: But not a living-wage job?

PH: I wouldn’t have wanted a weekly-critic [job], ever. I mean for a year, or few years. But all that grind and having to see so many boring films. Imagine poor Derek Malcolm now having taken over [as film critic at the London Evening Standard] from Alex [Alexander Walker]. He’s writing little paragraphs about 13 films a week. Who could bear it? I’d much rather write articles and reviews of films that I really want to write about than having that grind. If someone offered me a really good editorial job… but who would?

Then I had this notion that it might be quite interesting to write a history of the BFI. So I suggested that to Wilf, because they were still paying my salary for those final two years and might as well have something out of me. I thought it would be fun to write about all the scandal and the horrors. Then I thought about all the boring bits in between the interesting bits, and then I discovered they hadn’t kept any records… and then, I can’t remember how it came up, but I did the archives book [Keepers of the Frame, 1994], which was fun to do. The BFI financed the research. I enjoyed doing that.

CD: Did you have the same problem [with a lack of records] researching the Archive?

PH: No, because Lindgren’s records are wonderful, immaculately kept, as you would expect. The correspondence is all there – between the Archive and people like Hoellering back in the 60s, and indeed back to some of the big Hollywood companies in the 40s.

I remember filing a letter. The Archive had a lot of trouble with Paramount. There was a time when the Labour Government banned film imports because of a financial crisis we were in. And there’s a letter, this must have been 48 or so, from the Paramount man to the Archive, in effect saying: “We might consider giving you films if your government would relax this ban on film.” With the idea that the Institute actually had that kind of influence!

Correction (7 December 2015): This interview originally carried an incorrect transcription of the name of National Film Theatre programmer Ken Wlaschin, referring to him as ‘Ken Blashin’. This has been amended.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.