Talent aside, Bong Joon Ho owes much of his success to the fact that he’s a Hitchcockian director. He’s not given to slavish homages (he’s not a Brian De Palma) and he’s not obsessed with the psychology of suspense or the transference of guilt. But he does follow Hitchcock’s policy of meticulously pre-planning his films by fully storyboarding them, which leads him into intricately dovetailed plotting and gives him a keen sense of the way that suspense engages an audience.

Our March 2020 issue, guest-edited by Bong Joon Ho, is delivered to subscribers and available in digital editions on 3 February 2020. Buy a print issue, access the digital edition”]]

→

Parasite is released in the UK on 7 February.

Plus he’s acquired Hitchcock’s skill at playing with audience sympathies, often encouraging the viewer to identify with characters who behave badly or trip over moral dilemmas. He has a darkish sense of humour that matches Hitchcock’s, and perhaps also shares his penchant for the odd visual shock. (Psycho made a big impression on him.) Above all, he learned Hitchcock’s knack of disguising serious intent as entertainment. When he first visited London in 2000 – for the London Film Festival screening of his debut feature Barking Dogs Never Bite and to share the stage with Jia Zhangke at the ICA for a ‘new directors’ talkshow – I remember how pleased he was to spot a Hitchcock mug-shot peeping over the canopy of the Criterion Theatre on Piccadilly Circus.

Of course films are not the same as storyboards, and Bong has quite often been forced by adverse circumstances to change his pre-production plans. This was particularly true in the early years: Barking Dogs Never Bite (Flanders eui Gae, 2000) was nearly cancelled when its intended star pulled out at the last minute and its producer drastically cut the budget; Bong had to change some scenes and improvise others during production as he struggled to cope. He’s spoken frankly about this in a long interview with Jung Jiyoun, published in her 2008 book Bong Joon-ho.

Snowpiercer (2013)

The same interview goes into detail about the many changes he had to make in The Host (Gwoimul, 2006) to keep the CGI work down to affordable limits. Even Snowpiercer (Seolgyungnyeolcha, 2013) was almost derailed when the key production finance suddenly vanished while he was already prepping to shoot in Prague – and that was long before Harvey Weinstein told Bong that he wanted the film recut. (In Bong’s recollection, he was greeted in the Weinstein Company office in New York by Weinstein himself with a bear hug and the words “Director Bong, you are a genius!” before he was ushered into a side-room and shown the hatchet job the then-mogul had in mind.)

☞ Blockage on the line: Snowpiercer vs Scissorhands

The facts of life

It’s obviously more interesting to look at the films as released than to chronicle their sometimes fraught production histories, but we should first establish exactly who Bong Joon Ho is.

He was born in the city of Daegu in 1969, the youngest of four children of graphic designer and college teacher Bong Sanggyun and his wife, a former elementary-school teacher who suffered politically and economically for being the daughter of the distinguished 1930s novelist Park Taewon. (He defected to North Korea during the Korean War, and the anti-communist authorities in the South routinely punished relatives of such figures.) By his own account, Bong was a solitary and rather introverted boy who got good grades at school and spent much of his spare time drawing cartoons and comics.

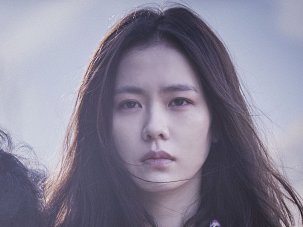

Parasite (2019)

He became a film fan in secondary school, watching whatever censored movies were shown on domestic TV and tuning to the American Forces Network – technically illegal, but even hotels did it – and started thinking about a career in filmmaking. His family was Catholic and he learned about the iniquities of South Korea’s military dictatorships and the 1980 massacre of unarmed civilians in Gwangju both at home and in Bible classes.

He read Sociology at Yonsei University in Seoul – the fake diploma made for the son Kiwoo in Parasite is headed “Yonsei University” – and, like most students of his generation, was an anti-government, pro-democracy activist. He was locked up for a month for joining an “illegal” Teachers Union demo and shared a cell with various “petty criminals” who later became prototypes for characters in The Host and other films. He was eventually given a suspended sentence on condition that he went straight into his mandatory military service, so he didn’t graduate from Yonsei until 1993. By then he had made his first short White Man (Baeksaek-in, 1993; it’s about a middle-class yuppie who finds a worker’s severed finger and pockets it) in a university film club where he also met his future wife.

From there he entered the Korean Academy of Film Arts (KAFA) for a couple of years, graduating with the remarkable short Incoherence (Jimimyeolryeol, 1994), which anticipates the themes, the sardonic humour and some of the visuals of his later features, including Parasite. It’s in three parts and an epilogue: the three parts show episodes of adult delinquency and the epilogue reveals that the three perpetrators are all supposed pillars of conservative society, discussing social morality on a TV talkshow.

Incoherence (Jimimyeolryeol, 1994)

Festival screenings at home and abroad soon made this the most noted KAFA student film ever. Bong and two of his classmates were snapped up as assistant directors by Park Kiyong, an earlier KAFA graduate, for his feature Motel Cactus (Motel Seoninjang, 1997), on which Bong also gets co-writer credit. During filming, Bong had special responsibility for keeping an eye on the often wayward cinematographer Chris Doyle. That job left him employed by Cha Seungjae’s company Uno Films (later renamed Sidus), for which he also co-wrote Min Byungchun’s Phantom, the Submarine (Yuryeong, 1999) and then directed his first two features.

What’s missing from this sketch of the early career is a sense of the social and political context. The struggle against authoritarian military rule – with all its martial-law provisions, its censorship, its economic controls and its violent suppression of dissent – dominated the 1970s and 1980s, producing an entire generation of ‘woke’ activists. Some of the restrictions were lifted in 1988, as Seoul hosted the Olympics and began turning Gangnam (the large area on the southern bank of the Han River) from farmland into a modern metropolis, but there was still plenty of tear gas on the streets of the city for the following five years as anti-government activism continued.

Palpable changes in the ways ordinary people spoke and behaved didn’t come until the civilian Kim Youngsam was elected president in 1993, but his regime’s cronyism and corruption guaranteed that cynicism and pessimism returned all too quickly. And two man-made disasters in Seoul in the mid-1990s consolidated the widespread feeling that something was seriously wrong at the heart of Korean society and politics.

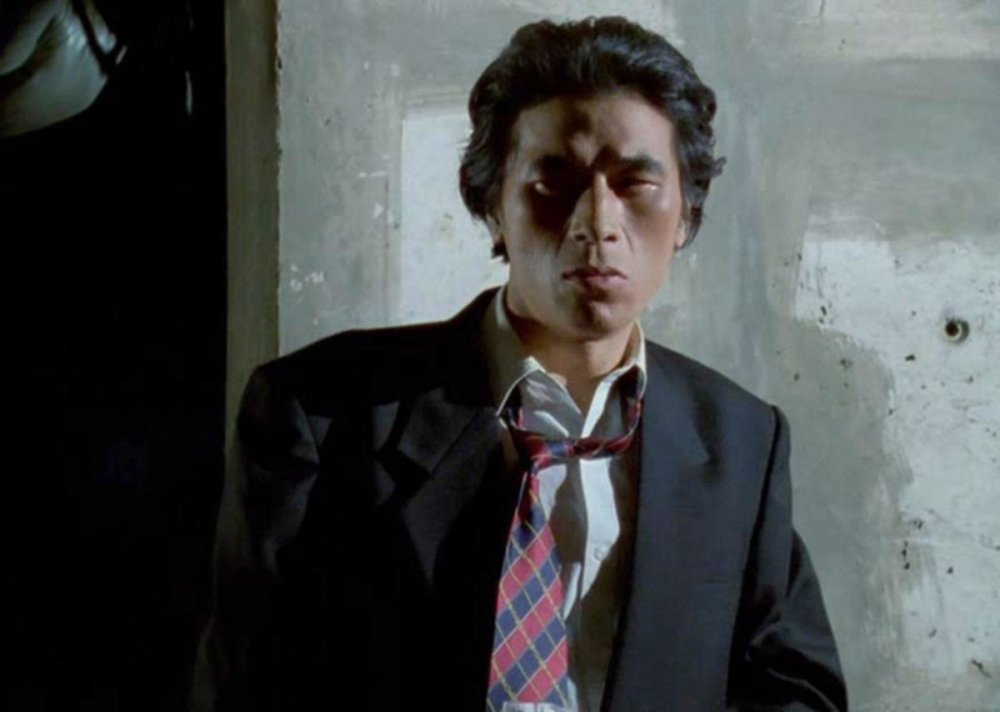

Memories of Murder (2003)

In 1994, a section of the Seongsu Bridge suddenly plunged into the Han River during the morning rush-hour, killing 32 commuters and schoolkids in the vehicles that were crossing it at the time. Only one year later the five-storey Sampoong Department Store collapsed equally suddenly, killing more than 500 people. Both catastrophes were blamed on shoddy workmanship and materials and traced back to lax governmental supervision; there was much speculation about bribery and corruption. Nearly two decades later the same public outrage reappeared, redoubled, when the Sewol ferry capsized and sank, killing hundreds of children on board, again apparently due to the cronyism which had allowed the disgraced owner to build a top-heavy vessel; there were also difficult questions about the training and responses of the captain and crew.

Bong’s films up to and including Parasite (Gisaengchung, 2019) have always reflected both the Korea he grew up in and his generation’s deep misgivings about the way their country is run. Paramount is the sense of social inequality – class division – which is obviously not confined to Korea.

More culturally specific are the direct echoes of social realities, such as the incompetence and propensity for violence of the police in Memories of Murder (Salin eui Chueok, 2003), which evoke the 1980s in the minds of Korean viewers as vividly as memories of the real-life unsolved crimes do.

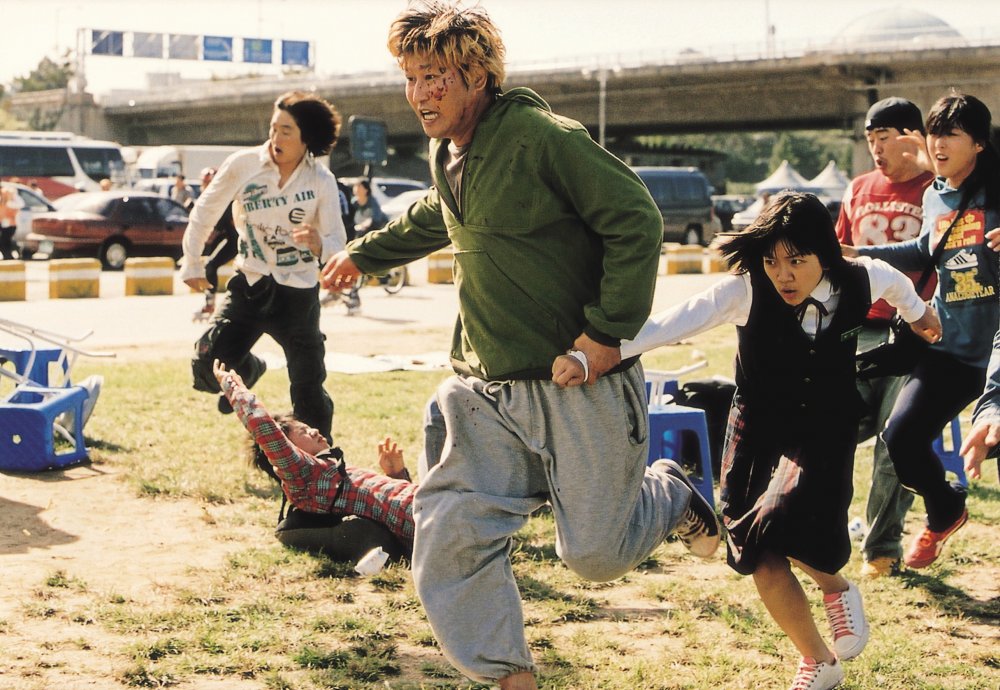

Or the mass evacuation of working-class civilians to holding camps in The Host when the authorities and a suspiciously compliant media spread the fake news that a contagious virus is more of a threat than the monster in the Han River – which finds a not-so-distant echo in Parasite when the Kim family is forced out of its basement home by floods and overflowing sewage. The two educated children in the Park family in The Host are both clear products of a student-activist background: the daughter Namju deploys her archery skills like a third-world guerrilla (you can imagine that she had a Che Guevara poster on the walls of her student digs) and the younger son Namil makes and throws Molotov cocktails with the ease of one who fought in the pitched battles around Seoul’s City Hall.

Sometimes Bong’s inspirations are directly personal. He has described Barking Dogs Never Bite – which he wanted to call ‘A Higher Animal’; he was overruled by a sales agent – as “my most personal film” and says, “I think my goal was to maintain and reveal my personal character.”

Barking Dogs Never Bite (Flanders eui Gae, 2000)

The film is not literally autobiographical, but the protagonist Yunju, a university lecturer who spends a summer bumming around in his modest apartment, hoping to be offered tenure while his wife is out earning their keep, is a metaphorical self-portrait of Bong in his late twenties as he tries to negotiate a role for himself in the film industry. The apartment is, in fact, identical to the one Bong and his wife lived in at the time. As played by Lee Sungjae, the character Yunju has a mild, placid exterior but is so irritated by the yapping of a small dog somewhere in the apartment building that he finds himself capable of monstrous acts: throwing a dog off the roof of the block and – a moral equivalent? – bribing the university dean to give him the job he wants.

Setting a pattern which stretches all the way through to Parasite, Bong spends more than half the film cross-cutting between two polar-opposite characters. Upstairs is Yunju, essentially doing nothing and allowing a minor irritation to become a major obsession. Downstairs in the estate management office is Hyunnam (played by Bae Doona, a TV star on the brink of her breakthrough in Korean and Japanese movies), a poorly educated but ethical and driven young woman with no career prospects who is unfailingly kind and considerate.

Bong’s smartest idea is to bring these two disparates together over the issue of lost or stolen dogs – which in turn leads him down to the lowest tier of the social pyramid, the basement where a dog-stewing security guard hangs out and the sub-basement where a hungry, homeless man is squatting. This, too, was anticipated in the short Incoherence, where a security guard’s rice-cooker is vandalised (I’m carefully avoiding spoilers here) in a most unusual way.

The most striking thing about this narrative structure is the way it refuses to conform to any generic norm. Barking Dogs fits no established conventions, not even the politically correct assumptions of 2000, which is probably why it took so long for Korean critics and audiences to notice it. CJ E&M didn’t publish the Korean Blu-ray edition until 2013.

Mother (2009)

Bong’s favourite genre is the crime thriller, but most of the crimes in his films go conspicuously unsolved. Indeed, Mother (2009) is the only one of his movies with that kind of narrative closure: a powerless but indomitable old woman goes into battle with the police and assorted low-lives to exonerate her falsely accused son, and wins – although even there the pay-off is handled quite unexpectedly.

The serial killings in Memories of Murder cannot be pinned to any of the three main suspects because the real-life crimes in the 1980s had not been solved when Bong made the film. (Last year, DNA forensics at last linked someone to the crimes.) The unresolved nature of the threat is an essential part of the way the film works.

The class rebels in Snowpiercer and the eco-activists in Okja (2017) are more heroes than criminals, but both films stress how limited their victories are. Actually, Bong’s instinctive retreat from orthodox generic endings and narrative closures is one symptom of his general ambivalence about genre. He’s happy enough to give his films generic identities, but even happier when he crashes the gears by making hairpin narrative turns or giving a dramatic scene a black-comic twist.

Monster success

The Host (2006)

Since Bong’s most critically acclaimed movies – Memories of Murder, Mother and now Parasite – are all relatively small-scale Korean projects, many have wondered what draws him to bigger and brasher spectacles (mostly in English) like Snowpiercer and Okja. This time it’s the cultural context which is crucial, although personal factors must play a part too.

The prime impulse is no doubt to crack bigger markets than the population (just under 52 million) of South Korea. Bong’s peers Park Chanwook and Kim Jeewoon had well-documented struggles to make English-language films in Hollywood, with Stoker (2013) and The Last Stand (2013) respectively, both seen as flops.

Snowpiercer, inspired by Bong’s interest in a French graphic novel, was clearly an attempt to follow in their footsteps but without going through the tiresome and frustrating process of negotiating with a Hollywood major. And then Okja came along in response to a non-studio funder’s carte blanche invitation (Netflix coughed up the entire budget without imposing conditions or making any changes), but at the cost of Bong’s preferred model of theatrical distribution. As ever, Bong was looking for a level of success on his own terms.

Okja (2017)

☞ Okja review: Bong Joon-ho’s rampant superpig spectacle tickles and troubles

We can only speculate about the personal factors. Bong had pitched the idea for The Host to a producer (essentially, the Loch Ness monster in the Han River) before he began Memories of Murder, but faced a series of small humiliations as he visited one far-flung visual effects company after another in his search for CGI on a budget. Snowpiercer and Okja exorcised those unhappy experiences by giving him uncompromised access to the visual effects he wanted. The Orson Welles dictum about a director having control of the full resources of a studio being like giving a boy the biggest train-set in the world may have played a part, too. And Bong’s cinephile awareness that – a couple of weak imitations of Japanese Godzilla movies aside – Korea had never produced a monster movie was another likely spur.

In 1960, Alfred Hitchcock, already well-known to audiences from his film cameos and TV intros, placed himself in a trailer and press ads to ask audiences not to give away the ending of Psycho. (This was in the days of continuous performances, of course.) In 2019, Bong prefaced the Cannes press-kit for Parasite with “A Word of Pleading”, which included these words: “Parasite is not a film that depends on one big twist at the end. It’s clearly different from, for example, a certain Hollywood movie that sent waiting audiences into a frenzy of dismay and anger when someone who’d just seen it screamed out in the lobby ‘Bruce Willis is a ghost!’” He went on to “implore” the critics to refrain from spoilers.

Subversively, he’d already slipped in a ‘spoiler’ of his own when he okayed the film’s main title design, which replaces the circles that are part of the Korean hangul script with spirals. That was his way of subtly hinting at the structure of the film’s plot. We’ll say no more.

-

The 100 Greatest Films of All Time 2012

In our biggest ever film critics’ poll, the list of best movies ever made has a new top film, ending the 50-year reign of Citizen Kane.

Wednesday 1 August 2012

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.