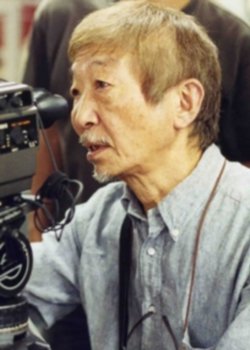

Tamura Masaki, one of the most impactful cinematographers of Japanese cinema, passed away on 23 May 2018. He was 79 years old, but his death and funeral was greeted with shock here in Japan; Tamura was a youthful old man, having directed the first feature film of his career, Drive-in Gamo, only four years before.

Few cinematographers have enjoyed as diverse a career as Tamura. He got his start in PR documentary in the mid-1960s. His employer, Iwanami Productions, was the filmmaking arm of a major publisher and its employees were on long leashes.

The directors and cinematographers at Iwanami brought an experimental spirit and scale (widescreen 35mm, and even love stories and implied sex) to PR films that inevitably ran into problems with sponsors. The most rambunctious and creative of the creative staff gravitated toward each other, spontaneously forming a kind of research collective called Blue Group (Ao no Kai). Tamura and his workmates assembled after work at a Kabukicho jazz bar called Narcissus; it’s still there, run by the daughter of the former owner who fondly recalls the energy of the Blue Group meetings. Members would run up large tabs while debating anything related to cinema – from theory to their individual projects. Blue Group was an incubator for both projects and talent; the directors would go on to become luminaries of the independent cinema and many of them tapped Tamura for his talent as a cameraman.

Virtually all of these filmmakers left Iwanami in the mid-1960s, including Tamura. He worked as co-cameraman or an assistant on the first films of Ogawa Shinsuke. And when Ogawa had a falling out with cameraman Otsu Koshiro (also from the Blue Group), Tamura became the main cinematographer for Ogawa Productions’ Sanrizuka Series and Magino Village Story.

Heta Village (Heta Buraku, 1973), part of Ogawa Productions’ Sanrizuka Series

Ogawa was quick to credit Tamura for his deep contribution to the collective. Tamura’s cinematography for the Sanrizuka Series, about the violent protests surrounding the construction of Narita Airport, swung wildly between different approaches. One minute he’s shooting an interview using extreme closeups and curious pans; the next he plunges – camera in hand and helmet on head – into melees between protestors and riot police.

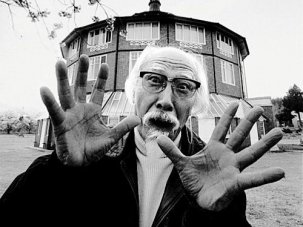

Tamura Masaki

The collective left a precious making-of film called Filmmaking and the Way to the Village (Eigazukuri to mura e no michi, 1973), that captures the relationship between Ogawa and Tamura. Ogawa Productions’ method involved long-term study and the development of trusting relationships with their subjects. They lived in the village of protesting farmers, and got to know them properly. The group would go out to the protests and film during the day, and then regroup at night for food, drink and debate. In the film, we see them watching rushes, and then starting a lively discussion. Clearly, Tamura is the only one who can keep up with Ogawa, who always dominated conversations.

Tamura had a peculiar relationship to Ogawa Productions. He never became a member, so was both inside and outside the collective. He and Ogawa were friends and collaborators, but they had their own falling out at some point. Over what, I do not know; but Tamura was a palpable absence in Barbara Hammer’s film about the group, Devotion (2000). He absolutely refused to be interviewed and rarely appeared for the regular retrospectives of Ogawa Pro’s work.

Still, I vividly recall Ogawa’s tsuya, or wake, which was held at a temple near the Ogawa Productions office in 1992. These are sake-fuelled social events when close friends and relatives gather to drink, talk about the departed, and do their best to stay with the body through the night. Even lively tsuya slowly calm down as people peel away, going home or going to sleep. Before I, too, succumbed to sleep in the wee hours, I was struck that Tamura-san quietly chatted with Ogawa’s wife in the darkness. The next morning, I learned he stayed with Ogawa until the sun rose.

Lady Snowblood (1973)

When I was writing Forest of Pressure, my book about the collective, I was grateful Tamura talked to me about Ogawa. I recall bitter stories over cheap maguro and beer in Nakano dives. He preferred to talk about the films. Tamura was particularly proud of Heta Village (Heta Buraku, 1973), which I count as one of the greatest documentaries ever made. Some of the scenes are stunningly formal – for example the long take that lovingly plays with the conical shapes of the straw hats of a group of women chatting over tea. More impressive and subtle are the discussion scenes. Tamura knew these people intimately, and thus understood precisely where to direct our attention – to devastating effect in the last scene of the film, which visually implies that one of the young farmers ratted out his friends to the police.

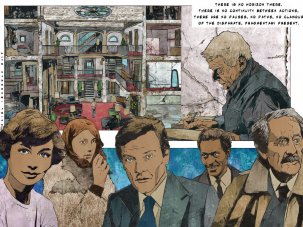

Tamura had an amazing 1973. In addition to Heta Village, this was the year he ventured into fiction with two historically important feature films. One was Assassination of Ryoma (Ryoma ansatsu) by Kuroki Kazuo, one of his friends from Iwanami and a key Blue Group member. Although it is a period film set at the transition between feudal and modern eras, Kuroki and Tamura brought a ironised, modernist sensibility to the true-life story of a rebel fighting the shogunate. At the same time he shot Fujita Toshiya’s Lady Snowblood (Shirayukihime). Here Tamura’s camerawork was more controlled – if brash and quick to give in to genre chaos – and he contributed some of the most iconic images of 1970s acttion cinema.

Tampopo (1985)

Tamura continued working with Ogawa Productions after its mid-70s move to northern Japan, when they set out on a 13-year-long, multi-film project on rice. As cinematographer, he wanted to break from conventional documentaries and searched for new visual strategies for representing the space and time of village Japan. He brought the lessons learned from these experiments with Ogawa to his celebrated photography for Yanagimachi Mitsuo’s Farewell to the Land (Saraba itoshiki daichi, 1982) and Himatsuri (1984). The former features spacey, writhing rice paddies seen from the POV of a drug addict. And in Himatsuri, Tamura probably came closer than anyone to rending the numinous onscreen, transforming a dark forest into a churning maelstrom of leaves as the main character hugs a massive tree (Tamura told me the secret: a helicopter hovering over the camera!).

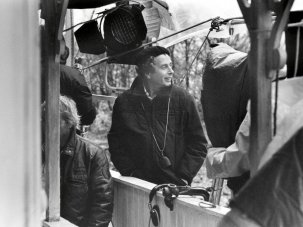

Tamura spent the rest of the 80s contributing charmingly creative camerawork to films such as Itami Juzo’s ramen romp Tampopo (1986), the warped cult film Evil Dead Trap (1988) and Okinawa director Takamine Go’s dreamy, folksy Untamagiru (1990). Then, in the last part of his career, Tamura-san made a very unusual contribution to Japanese cinema. At the top of his game, he quite self-consciously devoted himself to shooting films for young, up-and-coming directors – including Kawase Naomi, Suwa Nobuhiro, Hayashi Kaizo, Kurosawa Kiyoshi and Sato Makoto.

Eureka (2000)

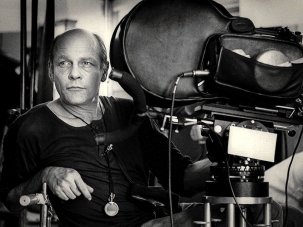

His most significant work was accomplished in a productive collaboration with Aoyama Shinji, starting with Helpless in 1996 and culminating with the luminous black and white photography of Eureka in 2000. Upon hearing of Tamura’s passing, Aoyama wrote, “When it came to originality, Tamura was someone impossible to imitate. Through that keen sensitivity, he inspired fear in some people and deep admiration in others. That’s the kind of person he was. For me he was, in the end, a gentle old man with a strong sense of humour.”

I am sure Tamura was both wonderful and difficult to work with. But he was always impressive. He led an impressive life. His family announced Tamura’s passing only after the funeral. I’m sure I am not the only one who spent an evening in a private tsuya thinking about Tamura’s life and work.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.