To adapt Napoleon, what was happening in the world when Peter Wollen was 20 was the breaking of the French New Wave at the 1959 Cannes Film Festival. For Wollen, then a student at Oxford, French critical theory and the American cultural forms that the French critics-turned-filmmakers loved – or Paris, Hollywood, as he would title one of his last books – constituted a pincer attack on all that was staid in post-war British culture. Godard’s À bout de souffle, released in 1960, “wasn’t simply rejecting Hollywood, aiming for a ‘European’ alternative, more cultured, more sophisticated, more sensitive,” he wrote later, but instead implied “a ‘refunctioning’ of Hollywood, and, by implication, of American mass culture”.

He belonged to a vanguard whose project was nothing less than the replacement of a national culture which “shunned theory even in its rejection of theory” with a new intellectual constellation composed primarily of pre-war “Western Marxists” like Antonio Gramsci and Walter Benjamin, and contemporary French thinkers, most of them writing under the influence of structural linguistics.

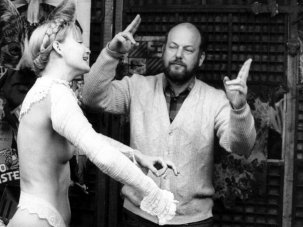

Peter Wollen

The vehicle of this revolution, after its takeover by Wollen’s university contemporary Perry Anderson, was New Left Review (eventually the begetter of Verso, publisher of many of Wollen’s books), and it was in this journal in 1963 that Wollen, writing under a pseudonym, made a preliminary bombardment of British film culture, embodied by Sight and Sound magazine and its editor Penelope Houston.

Behind Houston’s “fear of theory and ideology” he saw no possibility in British film criticism “of seeking to locate any film in any kind of structure greater than itself, historical, sociological or ideological. There is simply the egotism of the director and the egotism of the spectator.”

Locating or creating such a structure became Wollen’s task, achieved in the form of his first book Signs and Meaning in the Cinema, published in 1969. It appeared in the Cinema One series, the BFI’s first major venture into book publishing, which was jointly overseen by Houston and Tom Milne, representing Sight and Sound – and Wollen himself, then employed by the institute’s education department.

Most recently republished in 2013, Signs and Meaning is divided into three parts – one on Sergei Eisenstein, one on auteur theory, and one titled The Semiology of the Cinema, semiology being the science of signs, on the basis of which Wollen, in parallel with Christian Metz in France, sought to build a new aesthetic theory. Eisenstein had been the hero of two previous generations of film critics; Wollen, however, would locate him in a greater structure, that of modernism, notably the Russian formalist critics of the 1920s, the ancestors of Wollen’s structuralist generation in the 1960s. It was this intellectual range and curiosity that distinguished Wollen from the great majority of his contemporaries.

There was no solid institutional home for his scholarship: outside the art schools, film studies scarcely existed at this point. During the period of his involvement, however, the BFI’s education department became a gathering place for the film scholars-to-be of the 1970s; and in 1970-71 he and they were centrally involved in the great crisis that engulfed the institute, one of the results of which was the reconstruction of Screen, which the BFI supported, as the leading journal of film theory in the English language. Wollen was not its editor, but one might say it was remade in his image. At the same time, while Wollen went into academia, his writing never suffered from the obscurantism, pedantry and staleness that are the hazards of the trade.

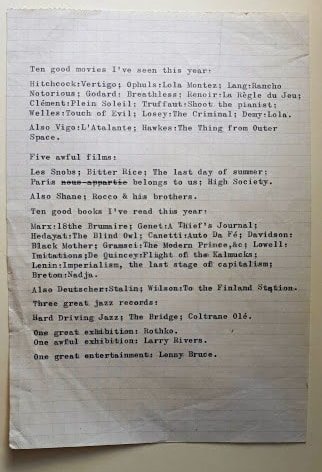

‘Ten good movies I’ve seen this year’: a note in Peter Wollen’s records in the BFI National Archive

“Looking back over this book, even after a short distance of time,” he wrote in 1972, introducing the second (technically third) edition of Signs and Meaning, “it strikes me that it was written at the beginning of a transitional period which is not yet over. What marks this period, I think, is the delayed encounter of the cinema with the ‘modern movement’ in the arts.”

What he had in mind was the reinvention of Jean-Luc Godard after 1968, and the arrival of “post-Godard directors” including Bernardo Bertolucci, Dusan Makavejev, and Jean-Marie Straub and Danièlle Huillet; and the breakthrough of mostly American or American-inspired underground cinema, associated with the New York and London Filmmakers’ Co-ops, around the same time. The hoped-for synthesis of these two tendencies would become the theme of his famous 1975 essay The Two Avant-Gardes.

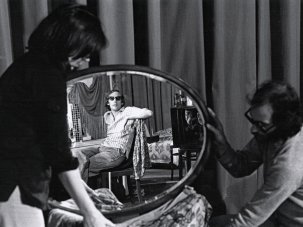

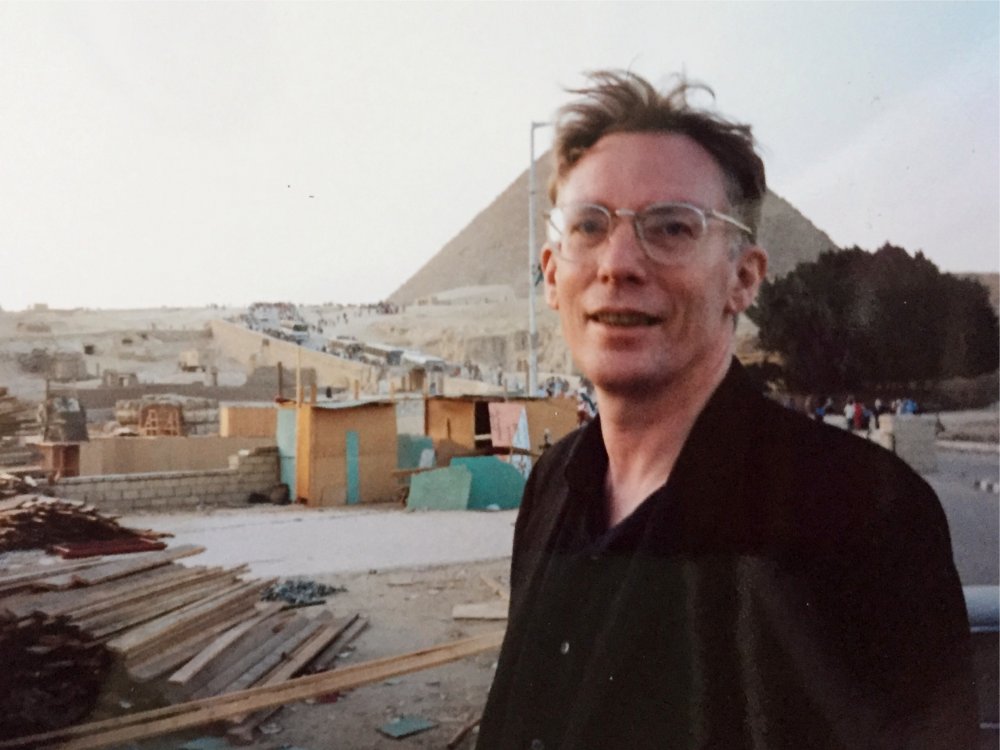

But even before it was published, Wollen had co-written a film that in many respects achieved it – Antonioni’s The Passenger, a metaphysical thriller starring Jack Nicholson and Maria Schneider, and released by MGM, that ends with a celebrated moving shot that brings to mind the Canadian experimental filmmaker Michael Snow. One of the possible keys to the film is in the conclusion to Wollen’s 1972 essay Counter Cinema, published in the little magazine Afterimage: “The cinema cannot show the truth, or reveal it, because the truth is not out there in the real world, waiting to be photographed.”

The Passenger (1975)

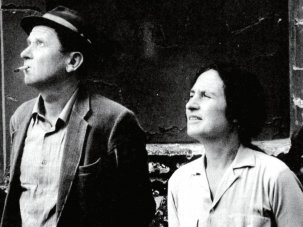

Interviewed by Time Out’s Chris Petit at the time of its release in 1975, Wollen said that “it’s more important for the cinema of this country that The Other Cinema – which distributes Penthesilea and similar films – and the Co-op survive rather than MGM.” Penthesilea was the first film that Wollen made with Laura Mulvey, a year earlier. The BFI-backed Riddles of the Sphinx followed, and their collaboration, straddling fiction and nonfiction, as well as the “two avant-gardes”, continued into the 1980s.

Wollen’s writings in that decade and into the 1990s – when he began writing for Sight & Sound after three decades on the outside – became less theoretical, more empirically historical, even biographical, notably in the case of Hitchcock, who, like Wollen, had moved from London to Los Angeles in mid-life. In 1993 he provided a possible “greater structure” for his and Mulvey’s films within British film history, in a dazzling essay titled The Last New Wave (published in the anthology Fires Were Started: British Cinema and Thatcherism, which argued that the real meeting of modernism and British cinema had come during the Thatcher era. Formidably learned, there is more in one of Peter Wollen’s essays than will be found in most books.

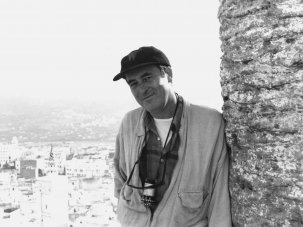

Peter Wollen’s notes and records, now deposited with the BFI National Archive

-

The 100 Greatest Films of All Time 2012

In our biggest ever film critics’ poll, the list of best movies ever made has a new top film, ending the 50-year reign of Citizen Kane.

Wednesday 1 August 2012

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.