Web exclusive

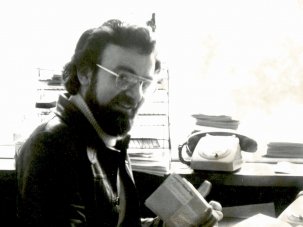

Credit: Tessa Perkins

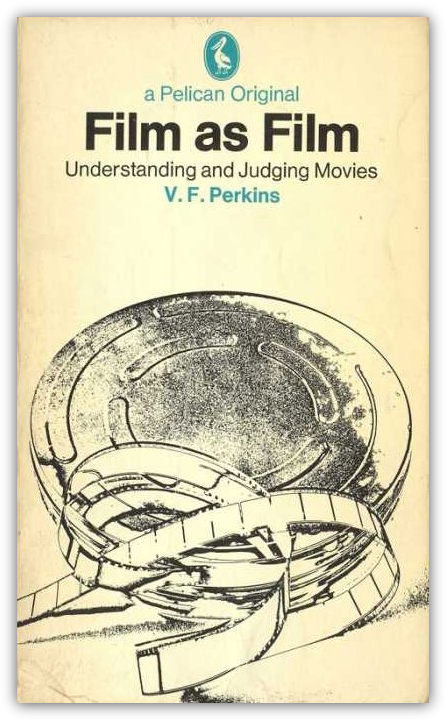

“This book,” runs the first sentence of the Preface to Film as Film, “aims to present criteria for our judgements of movies.” In his only full-length book, published in 1972, V.F. Perkins, who has died aged 79, laid out an argument for the evaluation of films based on their “subtlety, complexity or intelligence,” as expressed through their organisation of narrative and images to create coherent meaning. When we think about film as film, he declared, “we can value most the moments when narrative, concept and emotion are most completely fused […], where there is no distinction between how and what, content and form.”

Perkins argued his case through a series of detailed analyses and interpretations of key scenes from representative films, mostly made in Hollywood, such as Exodus, Bigger than Life and The Courtship of Eddie’s Father. His analyses explored the function and implications of details of performance, décor, space, camera angle and position, lighting and sound design. Logically, given this close attention to cinematic detail, Perkins championed the claim of the director to be regarded as the primary author of his films. As he wrote elsewhere, “The very breath of an actor can be made significant when the director places it in an expressive relationship with the other aspects of the scene […]. The director can bind the movie together in a design that offers a more personal and detailed conception of the story’s significance, embodying an experience of the world and a viewpoint both considered and felt.”

The aesthetic that Perkins championed in Film as Film had been developed over the previous decade in Movie, the magazine which Perkins had co-founded in 1962 alongside Ian Cameron, Mark Shivas and Paul Mayersberg (they were soon joined by Robin Wood, who, like Perkins, was to become a leading figure in English-language film criticism). The new publication built on the film criticism that Perkins, Cameron and Shivas had published in the Oxford University magazine, Oxford Opinion. There, they began to challenge the values and assumptions of Sight and Sound, then a publication of traditional liberal attitudes with a preference for international art cinema. The establishment of Movie gave Perkins and his colleagues a platform from which to promote a different view. Movie celebrated Hollywood cinema in particular, focused on the precise analysis of mise en scène, and insisted on the status of the director as author, even within a commercial system.

Although novel in a British context, the auteurist focus of Movie echoed the politique des auteurs which had been promoted since the early 1950s by the seminal Parisian publication Cahiers du Cinéma. However, Movie proved more rigorous than Cahiers in grounding opinions and interpretations in the concrete details of film style. In this, Perkins excelled: the central strength of his criticism lay in its combination of a precise attention to detail with a profound sensitivity to the emotional impact of cinema. Analytical rigour did not undermine emotional engagement, but rather, explained and justified it; Perkins admitted that he could be moved to tears by a film like Budd Boetticher’s Ride Lonesome. “To recapture the naive response of the film-fan,” he wrote, “is the first step towards intelligent appreciation of most pictures […] One cannot profitably stop there; but one cannot sensibly begin anywhere else.”

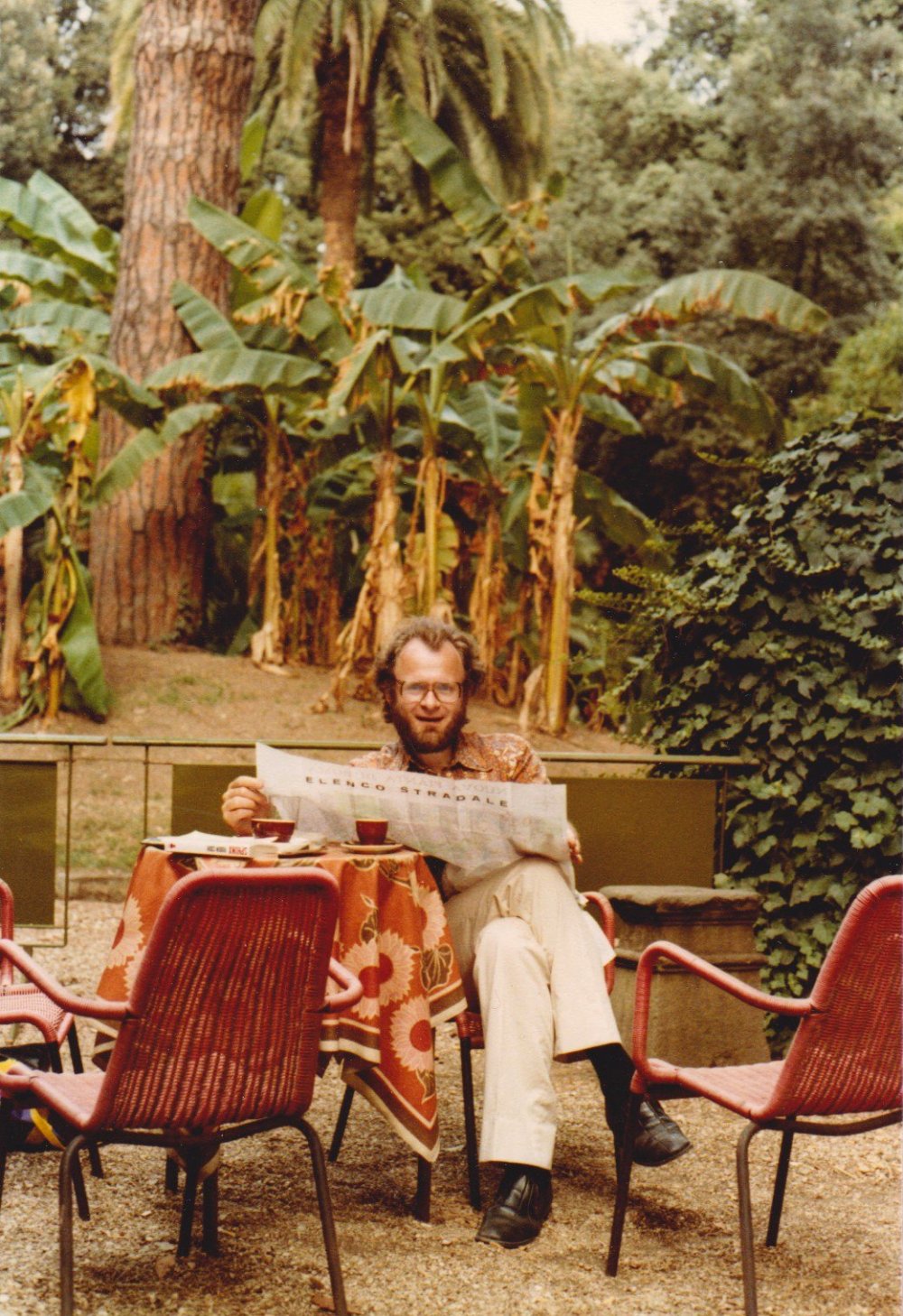

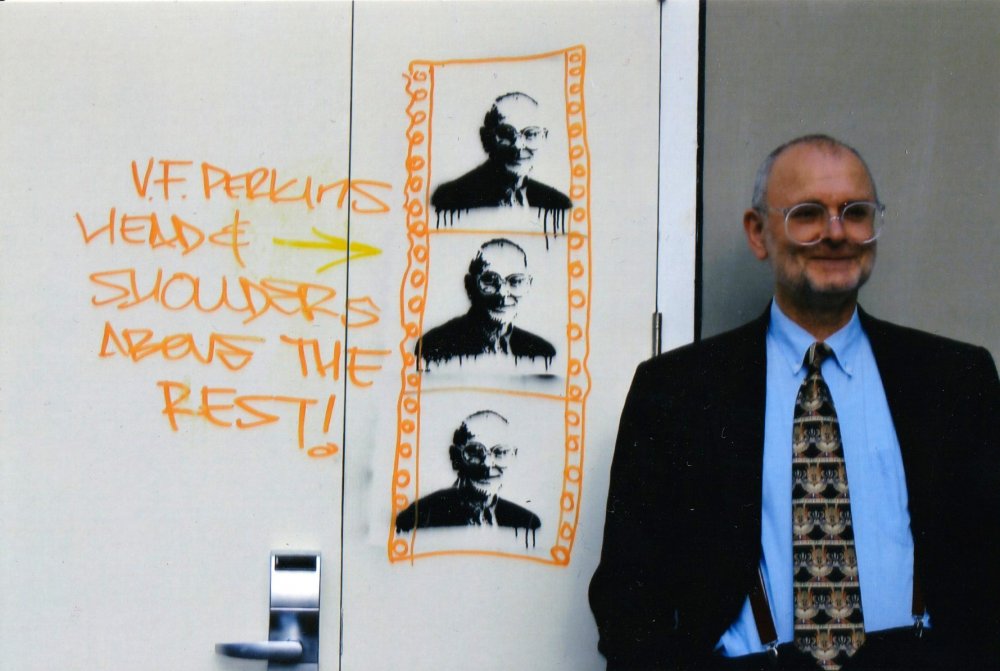

Victor Perkins in 1988

Credit: Polly Perkins

Such a credo led Perkins to appreciate the direct and intense, yet complex and subtle films produced by the finest exponents of the American studio system between the 1930s and the early 1960s. Championing classical Hollywood directors such as Hitchcock, Nicholas Ray, Vincente Minnelli, Otto Preminger and Richard Brooks, he was critical of the more self-conscious effects of European art filmmakers such as Eisenstein and Antonioni. Of the symbolic device of a red bedpost in The Red Desert, he wrote: “We are so busy noticing that we respond rather to our awareness of the device than to the state of mind it sets out to evoke.”

By contrast, he admired the more integrated symbolism of the American cinema: “to design an effect involves making it credible by locating it within the film’s world.” In a description of Preminger’s Exodus, he detailed the significance of the use of Greensleeves as an accompaniment to the death of a Zionist militant at the hands of the British military. The effect of the scene, Perkins argued, is crucially shaped not only by the connotations of the tune itself (the quintessential English melody), but by the fact that it plays plausibly on a car radio in an ironically cheerful jazzy arrangement. The film director’s strength, here as elsewhere, is his ability “to annul the distinction between significant organization and objective recording.”

Perkins’ critical writing was vitally complemented by his distinguished career as a lecturer. He was based at the British Film Institute’s education department before beginning to work in teacher training at Bulmershe College of Education (today part of the University of Reading). There, he set up a film studies programme which was one of the earliest in British higher education. In 1978, Perkins co-founded the Department of Film at the University of Warwick, which was to become arguably the most prestigious film studies department in Britain. He lectured there until 2004, after which reports of his retirement proved exaggerated; he remained a vital and active presence on campus, continuing to teach classes, attend film screenings and provide advice and inspiration to a younger generation of film students, scholars and critics. He was devoted to his students in and beyond the lecture hall; until his death, he helped to run a weekly Cinema Club on campus.

Perkins never sought to play the academic game and did not rise above the status of senior lecturer, though he received a well-deserved honorary professorship in retirement. His perfectionism ensured that he wrote relatively little. In the words of fellow film scholar Charles Barr, “he was like the kind of old-fashioned Oxford don who had one major work behind him from youth and never produced another, but who left a great legacy in the shape of shorter items, and his influence on a wide range of students, colleagues, and readers.”

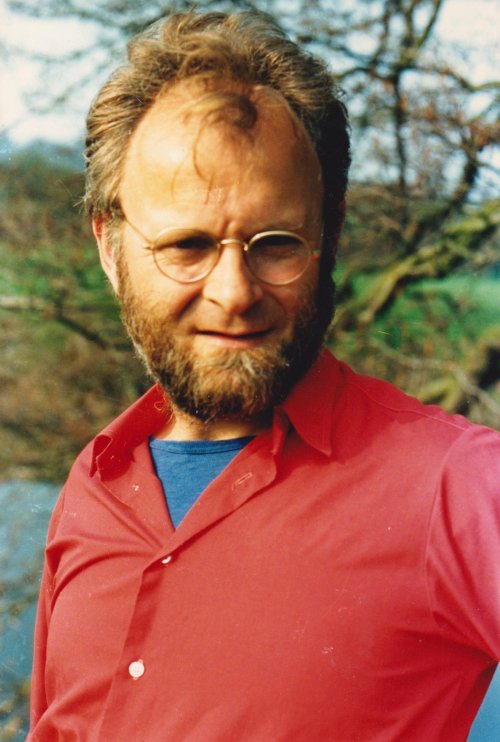

Credit: Joel Davey

But though his writing was sparing, the work that did emerge continued to demonstrate his customary acuity and precision. A particular devotee of Max Ophuls, he anatomised Letter from an Unknown Woman, Caught and Le Plaisir in extraordinary detail in a series of essays, while two BFI monographs addressed The Magnificent Ambersons and La Règle du jeu. As fashions in criticism changed, he contested what he described as “the premature burial” of auteurist criticism, and maintained his championship of the tradition of detailed close reading that had emerged from Movie. In doing so, he opposed the formalist approach of David Bordwell, which, despite its increasing domination of campuses, he saw as limited and simplistic. In a seminal essay, Must We Say What They Mean?, he challenged the American scholar’s approach and methodology. Where Bordwell, for instance, claimed that “There’s no place like home” was the explicit message of The Wizard of Oz, Perkins, pointing to numerous details of the film’s acting, narrative structure, visuals and soundtrack, argued convincingly that Dorothy’s words were “substantially qualified by the film’s other data” and that Kansas is shown to be “a place not remotely like home, a place lacking in courage, sensitivity, hope and colour, where the only singing that could be done was a lonely cry of yearning for something better.”

Victor Francis Perkins was born in Alphington, Devon, and educated at Hele’s Grammar School in Exeter. He won a place at Exeter College, Oxford, but national service intervened. Childhood memories of World War II had made a convinced pacifist, and only his mother’s intervention deterred him from going into hiding to evade the call-up. The experience of serving in Cyprus as an army radio technician reconfirmed his pacifism (in later life he was a supporter of CND). After completing his service, he took up his place at Oxford, where he studied history, and published his first film criticism in the student newspaper Varsity, and in Oxford Opinion. After graduation, while editing and writing for Movie, he worked initially at Selfridges before beginning his career in education.

Film Criticism: Interview with Victor F. Perkins, recorded at the Academy of Fine Arts Saar in 2011

Perkins’ interests in the arts extended well beyond cinema, spanning opera and the Broadway musical, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Vermeer, Dickens and P.G. Wodehouse, The Sopranos and South Park. He travelled widely, in Europe, North America and as far afield as Iran, and in his later years systematically acquired German in order to read a biography of Max Ophuls that existed only in that language.

His first marriage, to media theorist T.E. Perkins, ended in divorce. He is survived by their children, Polly, a writer and filmmaker, and Toby, Labour MP for Chesterfield, and by his second wife, Liz. His legacy will be sustained, too, by the many film scholars and critics who were shaped by his teaching and inspired by his analytical rigour and subtlety of interpretation. “For the very many people who fell under the spell of his work,” said Alastair Phillips, his colleague at Warwick, “he helped them see and think about the moving image more clearly.”

☞ Read and watch more tributes to V.F. Perkins at Film Studies for Free.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.