He was the man who made Heaven’s Gate. What an epitaph! The movie itself still evokes reactions as extreme as the lengths to which Michael Cimino went to fashion his magnum opus, but no one contests the film’s historical significance: it was the movie that brought down a studio (United Artists), and more than that, it made Cimino the whipping boy for the movie brats, the sacrificial lamb for the short-lived romantic notion that American filmmakers could be entrusted with the keys to the Hollywood kingdom. Released in 1980 (though it wasn’t really released at all), Heaven’s Gate could be considered the last hurrah of the Hollywood Renaissance, and the nail in its coffin.

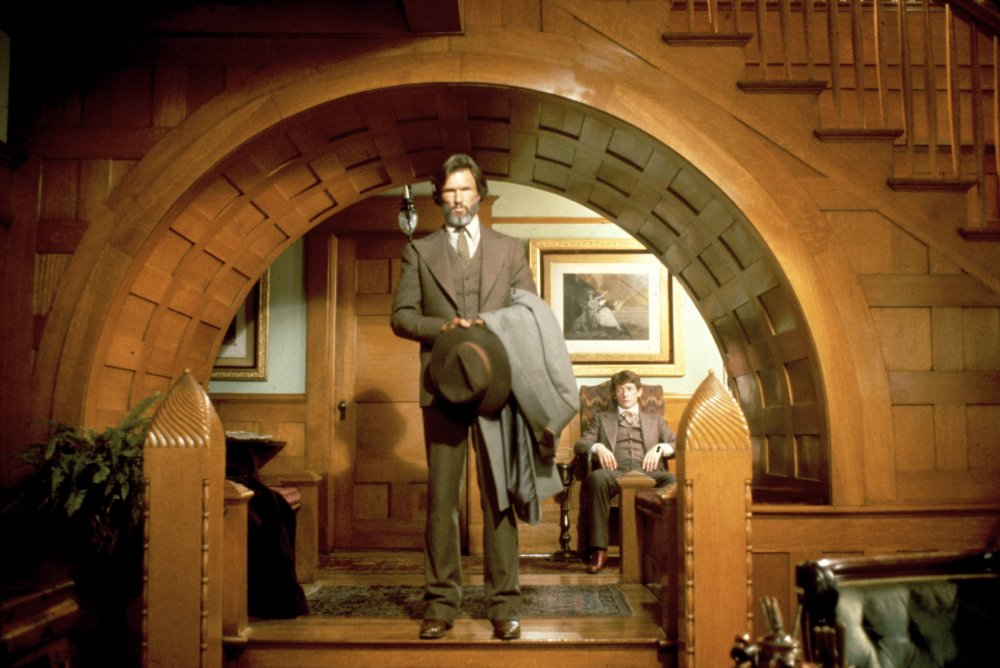

Heaven’s Gate (1980)

Like the Harvard gentlemen who oversee the slaughter of unruly immigrants at the climax of that much maligned but flawed masterpiece, Cimino came from an Ivy League background of wealth and privilege, graduating from Yale with an MFA in painting in 1963. From there he went to Madison Avenue, where he soon became a star commercials director of the Mad Men era, delivering bold, dynamic visuals for Kools, Eastman Kodak, and United Airlines, among others. Although he was the same generation as Francis Coppola and Martin Scorsese, Cimino can also be instructively placed alongside British advertising agency graduates like Alan Parker, Ridley Scott and Hugh Hudson: filmmakers schooled in creating highly polished vignettes underwritten by the almost bottomless budgets of corporate marketing. Even by the late 60s Cimino had a reputation for arrogance and perfectionism; the traits that would push Heaven’s Gate four times over budget were deeply engrained.

Michael Cimino filming Heaven’s Gate (1980)

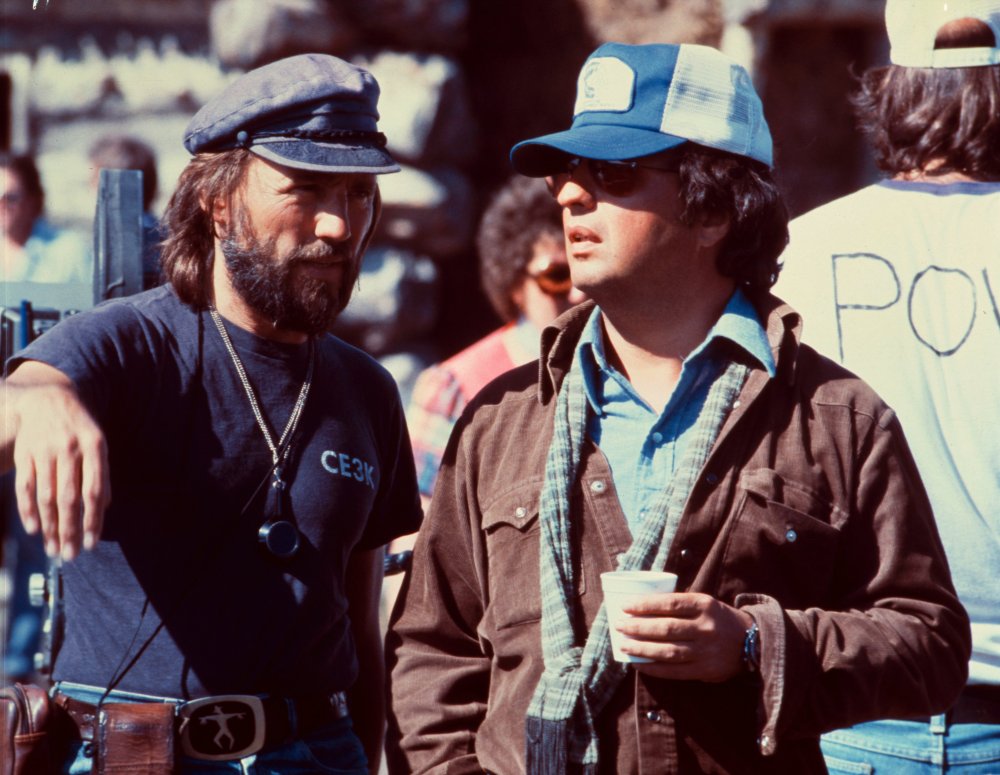

Cimino moved to Los Angeles in 1971. He was one of a trio of writers (Steven Bochco and Deric Washburn were the others) who collaborated individually with Douglas Trumbull on the screenplay of Silent Running (1972). His substantial rewrite on John Milius’s screenplay for Magnum Force (1973) so impressed Clint Eastwood that the star allowed him to direct his spec script, Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974). Set in Idaho and Montana – “big sky country” – this was a heist movie and a conflicted homoerotic buddy comedy, darkening palpably on the home stretch. Despite his inclination towards self-aggrandisement (Oliver Stone called him “the most Napoleonic director I ever worked with”), Cimino consistently spoke warmly of Eastwood’s mentorship and trust: “He taught me you have to will it into being.”

The Deer Hunter (1978)

The film was a hit but Cimino’s dream of filming Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead was destined to remain a dream (apparently Clint didn’t fancy filling Gary Cooper’s shoes). Eventually EMI bought a story about an American soldier who stayed in Vietnam after his tour of duty to play Russian Roulette. There would be disputes over writing credits with Washburn, but Cimino surely deserves the lion’s share for crafting the film’s audaciously low-key and unorthodox opening act: blue collar Russian-Americans going about their lives in a Pennsylvania steel town prior to shipping out to the war. The leisurely wedding sequence draws on The Godfather (even on its cast: De Niro and Cazale) and before that Visconti’s The Leopard, but the movie’s mixture of intimate observational detail and sense of epic grandeur represents Cimino at his finest. The sequences in Southeast Asia are intense but still problematic; nevertheless the first American war movie to begin to convey the nation’s anguish over Vietnam retains its cathartic power. The Deer Hunter won five Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director, and gave Cimino carte blanche on his next film, a western based on the notorious Johnson County War.

Heaven’s Gate (1980)

After Heaven’s Gate, Cimino made four more features. All are characterised by their rich visual palettes (even the claustrophobic kidnap drama Desperate Hours (1990) has his favoured anamorphic sweep) and express an oddly classical romanticism, but this burnished and expansive style only made the screenplays underneath seem more threadbare and inadequate. There are moments of poetry and ragged passion in The Year of the Dragon (1985), The Sicilian (1987) and The Sunchaser (1996) but also long passages of incoherence and naivety. He always seemed to be reaching for a grandeur just out of reach. We’ll never know if he had another great film in him: The Fountainhead and Malraux’s Man’s Fate were among the projects that got away.

The Year of the Dragon (1985)

Michael Cimino was 77.