Web exclusive

Moving Creatures

This year’s São Paulo International Film Festival included more than 350 films on 28 screens across the city in central urban areas, poor suburbs and open-air venues. The Mostra, a festival for the public, offered a bit of everything. Film history was prominent, as viewers watched DCP prints of The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp and Once Upon a Time in the West between screenings of new films in the same rooms. The keen filmgoers I talked with were eager to attend the 35mm Tarkovsky retrospective, and most curious about the films of Shibuya Minoru, who enlisted several of Ozu Yasujirô’s stock actors in TohoScope comedies about adult males behaving like infants. At one point I had to choose between neighbouring screenings of a hot new film and a Chris Marker double-bill; when the new work sold out, I sighed in relief.

|

São Paulo International Film Festival Note: Though the writer worked as a programming aide for last year’s São Paulo International Film Festival, he did not help select any of the films discussed here except Far from Afghanistan and A Beautiful Valley. |

The 36th Mostra, which unfolded over a year after its founder and lifetime director, Leon Cakoff, died of cancer (Renata de Almeida, his wife, has since assumed full directorship), looked back and forward, with full retrospectives of filmmakers Sergei Loznitsa and Miguel Gomes accompanying their new films In the Fog and Tabu.

One could look, too, from side to side, and catch the dialectics of conventional narrative and more experimental approaches to similar subjects. The earnest, naive concern for Afghans living under Taliban rule as expressed through the first-person perspective of the American musician and filmmaker Ariana Delawari’s We Came Home, the Mostra’s international documentary prizewinner, contrasted with the fractured anger expressed by the many near and distant filmmakers of Far from Afghanistan, an omnibus act of protest against the American government that helped put the Taliban into power to begin with and that, even years after killing bin Laden, continues to perpetuate the decade-plus war.

Fill the Void

The third-person-close form of Rama Burshtein’s international dramatic prizewinner Fill the Void (Lemale et Há’halal) – an Israeli film about a young Jewish Orthodox woman considering a marriage proposal from her dead sister’s husband – threw the welcomingly multi-faceted viewpoints of other Israeli films into relief. Hadar Friedlich’s debut feature A Beautiful Valley (Emek tiferet) gazed gently but firmly upon the interactions between several kibbutz residents, focusing on an older woman searching for solidarity as she’s pushed towards retirement.

The master Amos Gitai presented two intimate films, 2009’s Carmel and this year’s Lullaby to My Father, in which he discovers and retells stories of his parents. As he collects photographs, journal entries, and memories in the second film, we hear a voice say: “People leave you fragments, and they tell you, ‘Listen, if you’re interested, you can do something with it.’”

These films placed a value on education, with their protagonists learning from older family members and others in their immediate proximity. So did the Russian film Tomorrow, Andrey Gryazev’s documentary portrait of the interventionist artmakers of the Voina Group. The group has gained notoriety for public disturbances including having a member running through Moscow with a bucket on his head and turning over a police car, but the film shows them committing their actions with the specific goal of helping people grow more aware of the social structures that are constricting individual freedoms. The infant son of Voina’s chief couple accompanies his parents throughout everything they do, the better to help him grow up to decide how he himself wants to live.

Soldier/Citizen

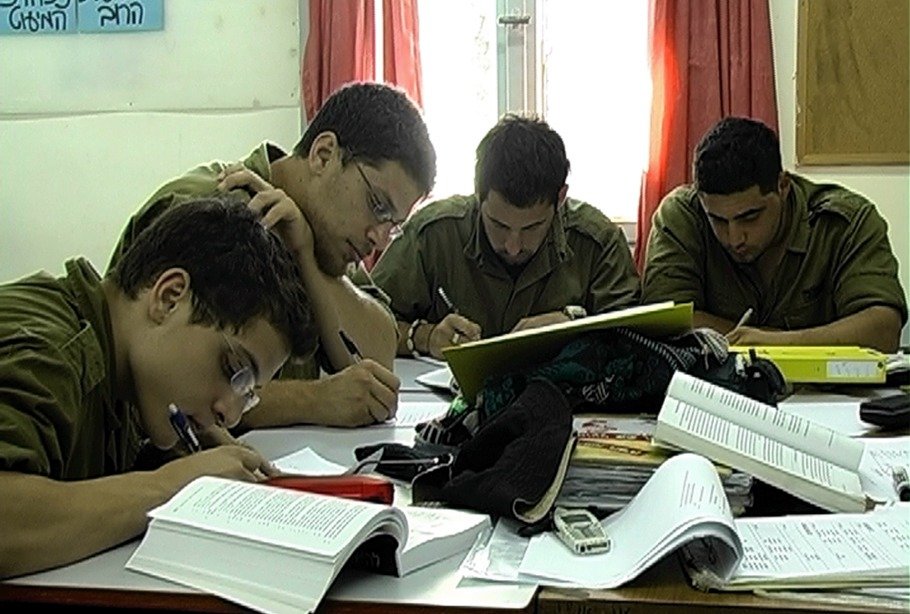

Tomorrow argues that good teachers expose their students to challenging new information and ideas, and then leave them to create their own analysis. So does the Argentina-born Silvina Landsmann’s documentary Soldier/Citizen (Bagrut Lochamim), which unfolds mainly inside an Israeli classroom where young soldiers finishing service requirements debate civics in order to earn their high school diplomas. Their rigorous yet patient teacher Eyal works to figure out what they think, and then to challenge their thinking, especially about the Occupation of Palestine.

In response to his students’ resentment against Arabs for not serving in the Israeli army, Eyal tells how the Israeli government has denied them the ability to do so, as well as many other citizens’ rights; when students say that Palestinians should leave the Occupied Territories, Eyal responds that they have nowhere else to go. Whenever he hears the words ‘they’ or ‘them’, Eyal asks who exactly is being discussed. He shakes his head and says he takes comfort in remembering how, when he was younger, he felt like his students did. Several claim that the military has helped them grow cold and blind, but at film’s end we hear that border troops will now be taught basic Arabic.

The Brazilian films I saw and liked were also good educational tools. Save for Maria Brennand Fortes’s Francisco Brennand, a straightforward guide through the work of an 85 year-old sculptor, muralist, and painter as told by him in person and through diary entries read aloud in voiceover, they were less didactic and more impressionistic.

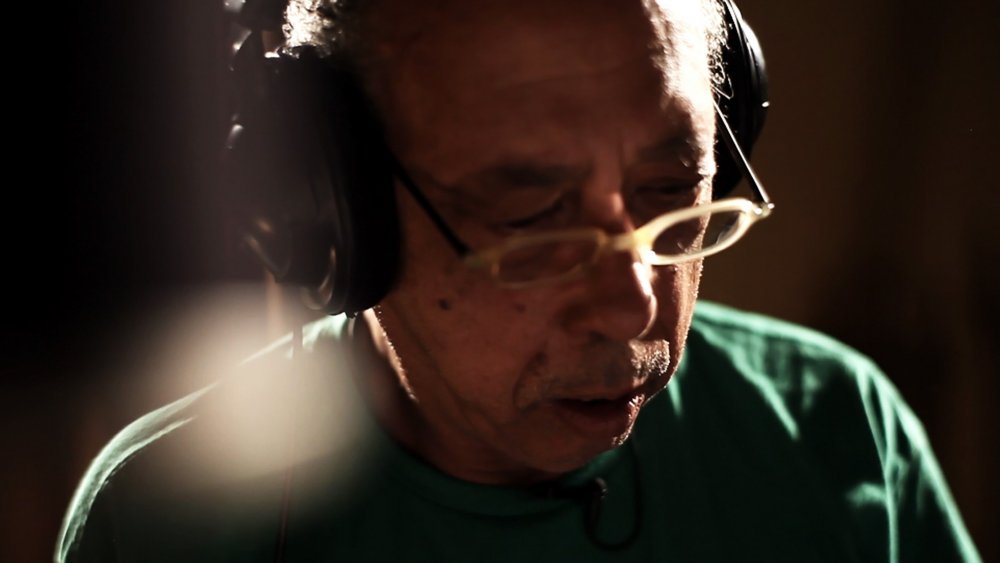

Jards

Eryk Rocha’s musical documentary Jards rendered the wonderful contemporary musician Jards Macalé’s thought process in largely wordless, vibrating photography whose style shifted according to his state of mind. Kleber Mendonça Filho’s Neighboring Sounds, the Itamaraty winner for best narrative, examined the social dynamics of a suburban neighbourhood with paranoid residents by rendering the distinctions between actual and imagined threats ambiguous, thus leading the viewer to question his or her own prejudices.

Considering how many festival prizes Sounds had already received both in Brazil and internationally, its victory should have shocked no one. Yet, although I believe Mendonça’s to be a great film, I also wanted to look around. The movie I missed for Chris Marker, and then later caught, was one of Sounds’s competitors, Caetano Gotardo’s debut feature Moving Creatures (O Que Se Move, pictured at top). Gotardo works with Filmes do Caixote (Box Films), a São Paulo production company whose member’s roles rotate; he edited last year’s fantastic Trabalhar Cansa (Hard Labour), and its co-directors have edited this new film and composed its music.

While the previous feature plunged deep into black comedy to show how desperately people could behave to secure a job, Creatures’s tone is lighter and softer, as well as harder to place. Its three stories show mothers passing through different stages of loss; the collection gives different ways that mourning can look, as well as suggesting ways hidden from view. There are songs, too, providing not so much catharsis as brief lifts. Catharsis would imply an ending, and Creatures suggests that endings are temporary.