Web exclusive

A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence (En duva satt på en gren och funderade på tillvaron, 2014)

Getting the prizes right, as the Venice jury has this year, might seem an easy achievement when a festival is as thinned out as I have already complained this one was. Yet the last five days were stronger than the first five, and as a whole it amounted to the kind of programme that festival director Alberto Barbera says he wants in future – one more about discovery of new directors and films than with showcasing Hollywood on the Lido. Laudable as that aim may be, it will be interesting to see if the powers behind the festival will tolerate the consequent decline in international interest that will surely follow.

La Biennale di Venezia

27 August-6 September 2014 | Italy

THE AWARDS

Golden Lion for Best Film

A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence (Roy Andersson)

Silver Lion for Best Director

Andrei Konchalovsky for The Postman’s White Knights

Grand Jury Prize

The Look of Silence (Joshua Oppenheimer)

Best Actor

Adam Driver in Hungry Hearts (Saverio Costanzo)

Best Actress

Alba Rohrwacher in Hungry Hearts (Saverio Costanzo)

Marcello Mastroianni award for Best Young Actor or Actress

Romain Paul in Le Dernier coup de Marteau (Alix Delaporte)

Best Screenplay

Rakhshan Banietemad and Farid Mostafavi for Ghesseha (Tales) (Rakhshan Banietemad)

Special Jury Prize

Sivas (Kaan Müjdeci)

However thin the competition, it was happily appropriate that the most extreme work of authorial exactitude on show, Roy Andersson’s magnificent ‘third part of the trilogy’ A Pigeon sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence, won the Golden Lion. Like its predecessors Songs from the Second Floor and You the Living, A Pigeon… is made up of interlinked sketches, most of which here concern Sam and Jonathan, lugubrious pals who sell novelty items, such as vampire teeth and Uncle One-Tooth masks. If you’re not careful about what you read, you’ll also hear too much about Limping Lotta’s Gothenburg bar where the troops of 1943 can get a shot of liquor in exchange for a kiss, and about the visit of King Charles XII to a present-day greasy spoon that plays a great rock ’n’ roll song called ‘Shimmy Doll’.

That Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Look of Silence won the Grand Jury prize and that Adam Driver and Alba Rohrwacher won the two acting prizes as the best things about the flawed relationship drama Hungry Hearts (see my last post for both) could not be argued with. But I was mildly surprised that Andrei Konchalovsky won the Silver Lion for best director with his semi-improvised lakeside drama The Postman’s White Knights. Shot in a lo-fi digital format, the film follows Lyokha, a sad clown character played winningly by real postman Aleksey Tryapitshy, as he scuds across the lake in his speedboat and links together various minor made-up dramas, all portrayed with panache by real locals. The film has much sympathetic crowd-pleasing charm and some great shots, and gives a keen insight into rural Russian life – but it also cleaves to the cutesie every chance it gets.

Red Amnesia (Chuǎngrù zhě, 2014)

I preferred Wang Xiaoshuai’s Red Amnesia, a subtly complex intrigue that focuses on Deng Meijuan (played by stage veteran Lu Zhong), an elderly Beijing grandmother, just as she’s reaching an age where her two sons – one a well-off family man, the other a gay hairdresser – are considering her future. She lives alone in her own apartment, yet constantly tries to interfere in her offspring’s lives. Her building suffers from regular break-ins, and a young man in a red baseball cap may be stalking her. These elements are handled deftly to stimulate genuine suspense and intellectual curiosity as the hidden historical nature of the threat to her comes slowly to the surface. The only aspect that mars this well-constructed and expertly acted film is the very ordinary digital cinematography.

Venice has always made a strong point of its Asian selections, and if this year’s success rate was down there were some exceptions worth seeing. I wouldn’t include, though, Shinya Tsukamoto’s Nobi (Fires on the Plain) – a somewhat tawdry gorefest-remake of Kon Ichikawa’s 1959 classic about Japanese soldiers in World War II being abandoned to starve on the Indonesian island of Leyte – though it does have the most terrifying machine-gun mass-slaughter scene since Spielberg’s Omaha Beach opening to Saving Private Ryan.

Hwajang (2014)

I would, however, include Im Kwon-taek’s Hwajang, a gentle melodrama about a marketing boss whose wife is slowly dying of cancer just as a hot new ambitious hireling takes up her post outside his office. If the portrayal of May-September power lust is merely gestural, the depiction of the true and sometimes harrowing meaning of care and companionship is nearly as substantial as that seen in Haneke’s Amour.

Hong Sangsoo makes too many films – or rather too many to keep up with, though one keeps trying them. I was going to skip Hill of Freedom, assuming – correctly – that it would be another light fable of earnest, embarrassed meetings in bars and restaurants, but I’m sort of glad I didn’t, since it adds yet another variation to his accidental-collisions-of-life pattern, in that the protagonists here are all speaking English as a foreign language and the sequence of events depends on a letter being read out of sequence.

The titular Hill of Freedom is a coffee shop in Seoul’s Bukchon village, the letter-writer is Mori (Ryo Kase), a Japanese returning to the city in search of his paramour, Kwon (Seo Young-hwa) the letter-reader, who was/is away for most of Mori’s visit (told in flashback), and who reads how, while hanging out at the coffee shop, Mori began an affair with its owner, Young-sun (Moon So-ri). Much mild hilarity ensues over its 66 minutes and, if it feels at times as if the whole thing might collapse at any moment, you somehow forgive it its amiable laziness. (The French influence this time, by the way, is more Resnais than Rohmer.)

Pasolini (2014)

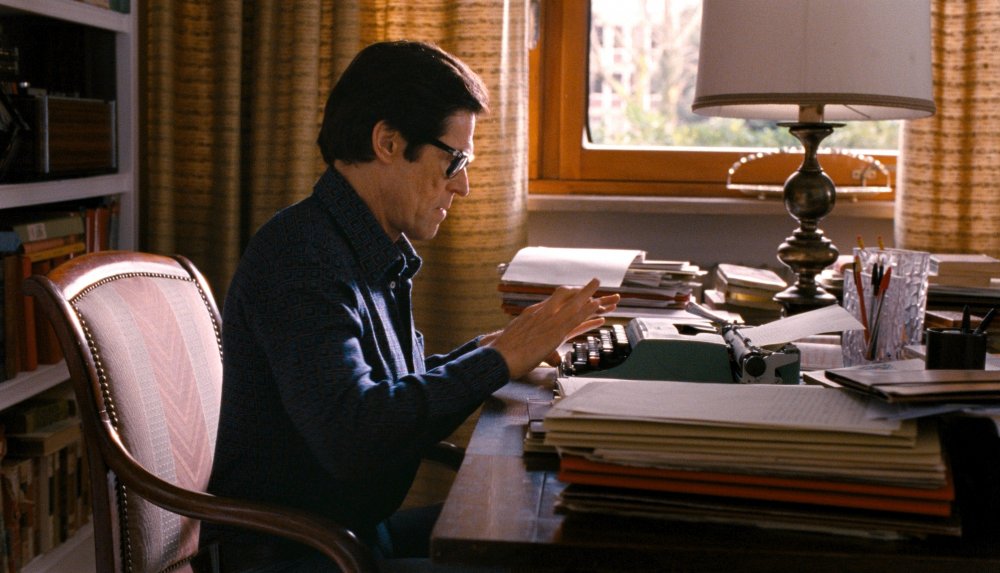

With great self-assurance, Abel Ferrara’s Pasolini imagines the last day in the life of Italy’s most passionate great director, not merely through dramatisation but also through imagining and evoking the unrealised projects that may have been running through his mind as his day moved towards his notorious murder, the act which sadly dominates public memory of him.

The largely Italian audience I watched it with gave the film a muted reception, which Italians I spoke to afterwards put down to the film’s one-day focus, its jumping between English and Italian speech and choice of a homophobic murder rather than the political killing many Pasolini fans believe happened. As a detester of the average biopic, however, for me Pasolini deserves great credit for its imaginative interleaving of a many-threaded identity into one succinct 83-minute experience: Dafoe incarnates the look of Pasolini, his voice has the right authority and the 70s-style dark-lit-corridor cinematography gives it the right kind of elegance and polish.

Theeb (2014)

The festival’s one charming discovery was what people are already calling an ‘Arab western’ and yes, Naji Abu Nawar’s Theeb fits that description as well as the excellent Far from Men (mentioned in my last post) fits the tag ‘Algerian western’. Yet Theeb is an even better fit as an antidote to the imperial swagger of Lawrence of Arabia.

Set in the same time and place as Lean’s great epic, Theeb follows the fortunes of the titular feisty young Bedouin boy who, when his brother is asked to guide an Englishman across the desert, secretly tags along and witnesses disaster at a well. It’s a taut adventure yarn for sure, directed by a sure hand. If this sort of discovery is Venice’s future then it may not be so deflationary a prospect after all.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.