Web exclusive

A Story for the Modlins

I’ve been coming to this monumental celebration of short films since 2009, yet still feel dazzled by the quantity and variety on offer, as well as the long queues for its screenings. What remains extraordinary is that only a portion of these eager spectators are marked by fluorescent lanyards and the signature festival bag as ‘film professionals’: the majority are in fact regular citizens of Clermont, this small, hard-working, rugby-loving French industrial town that otherwise hosts tyre giant Michelin, a lively student community and the locations of Eric Rohmer’s New Wave gem My Night with Maud. Over its 35 years this festival – the biggest film festival in France after Cannes – has carved a place in the life of locals who every year rub shoulders with thousands of international industry professionals and join the fervent improvised post-screening debates in the cafes and bistros around the festival venues.

Notwithstanding the daunting 18-venue timetable that opens the catalogue, three competitive strands provide the main axes of the festival. There’s the French competition displaying the latest samples of a notoriously fertile and wealthy short-filmmaking culture, an international competition, and the Lab, devoted to more experimental, boundary-pushing (albeit still fairly accessible) content.

Next year will mark the tenth anniversary of what could be described as the ‘Amalric file’, the (in)famous decision made in 2004 by jury president Mathieu Amalric not to award any prizes due to the poor quality of the films in competition. No such conundrum affected this year’s juries, who added a considerable number of special mentions to the official awards.

Avant que de tout perdre

In the French competition, the Grand Prix went to actor Xavier Legrand’s harrowing directorial debut Avant que de tout perdre, wherein restless and unadorned camerawork built masterful narrative tension around a woman’s race against the clock to run away with her two children from an abusive husband. It struck a chord with the public too, also winning the audience award.

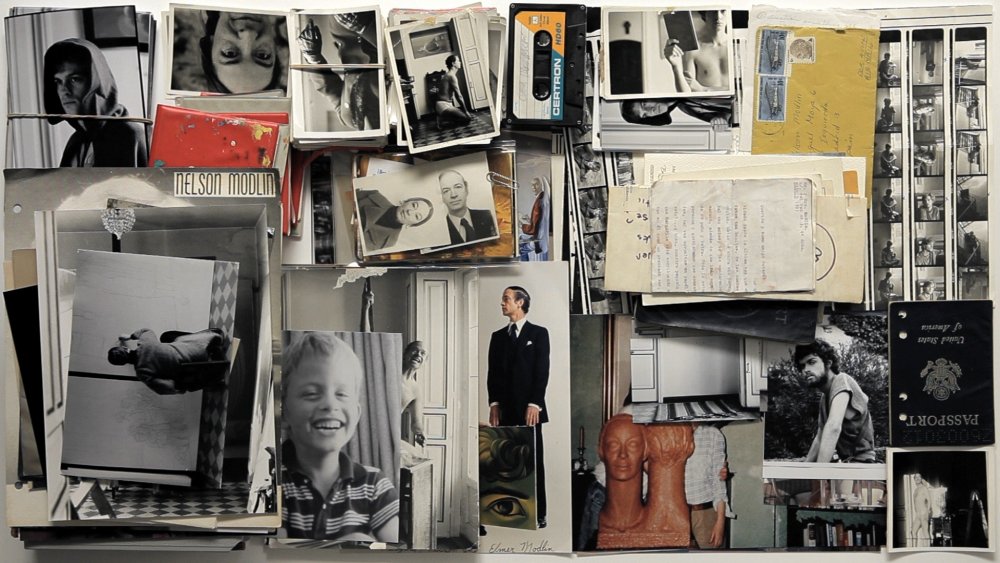

Audience and jury prizes also converged in the prize list of the Lab competition, whose Grand Prix was awarded to Spanish filmmaker Sergio Oksman’s enigmatic and beautifully crafted A Story for the Modlins (Una historia para los Modlin), a documentary attempting to piece together the life of Elmer Modlin, a struggling actor who managed to get a role as an extra in Rosemary’s Baby, then disappeared with his family. Photos, collectibles and general clutter found in a rubbish bag outside his flat provide the raw material for what’s both a technically brilliant (re)construction of events and a fascinating study of the porous boundary between life and art.

A Story for the Modlins also haunted some of the works on display at the Anatomie du Labo, the nonchalant exhibition which every year invites a group of young visual artists to respond to anything in the Lab competition. The result is a fascinating, anarchic and unpredictable array of complements, interpretations, dissections or utter transformations of films in the programme.

From the 14 (!) international programmes, the Grand Prix was won by Mexican filmmaker Isabel Acevedo’s To Put Together a Helicopter (Para armar un Helicóptero), a quiet, slow-paced and heartwarming observation of a community of immigrant farmers living a Mexico City slum and their daily struggles and resourcefulness in the face of the city’s temperamental electricity supply and torrential rain.

Britain’s presence was also particularly strong at this year’s festival, with 14 films selected in competition, two of which went on to obtain special mentions: Shaun Clark’s darkly funny animation Lady and the Tooth [homepage], in the Lab, and Fyzal Boulifa’s excellent The Curse, a poignant and minimalist drama set in the Maghreb desert, where a young woman’s tainted reputation leads to blackmail and humiliation within her local community.

Beyond the competitions, India was the country in focus with a seven-programme retrospective offering an exhaustive overview of its most significant shorts from the past decade. This rich body of work certainly included its share of moral tales and sentimental overtones, but there were also sharp exposés of the country’s dark side, such as Manish Jha’s 2001 Cannes jury prize-winner A Very Very Silent Film, a brutal depiction of the physical humiliation experienced by homeless women in modern-day India.

The crossroads between short film and science provided fertile ground for ‘Imaginary Particles’, an eclectic retrospective exploring filmic ideas of time, space, movement and the mystery of life, often repurposed by filmmakers in imaginative and gloriously unscientific ways. The ‘particles’ here ranged from Chris Marker’s seminal La Jetée to more recent, playful insights into the mysteries of the physical world such as Big Bang Big Boom, Italian artist BLU’s monumental graffiti animation charting the evolution of the species on painted urban wasteland (above), or the visual wizardry of German faux-documentary The Centrifuge Brain Project (below), in which the mechanics of amusement parks rides are pushed to an extreme in an attempt to enhance people’s brain capacity. Incidentally, at one of these screenings I was reminded of the near-ubiquity of film festivals when I discovered the existence of CineGlobe, a science-film festival taking place at CERN, the European Organisation for Nuclear Research!

As short films find increasing exposure on various internet platforms and festivals are caught in the debate around free online content availability, Clermont-Ferrand has always proudly eschewed any sort of exclusivity by foregoing ‘premiere status’ claims and other kinds of online-related restrictions. In what could be read as an attempt to reinforce this position and further embrace the productive exchanges with internet-based content, this year the festival devoted its regular ‘Decibels!’ strand – a programme celebrating music and short film – to a retrospective of the Paris-based music-sharing internet platform La Blogothèque and their cult ‘Take Away Shows’ – shorts filmed with minimum equipment in which famous bands perform live in unusual urban settings. Arcade Fire, Phoenix, Bon Iver and Beirut were some of those featured. (As they wrote in the festival catalogue, the Blogothèque founders never imagined their commissions would one day cross the ether onto a cinema screen at a prestigious international festival.)

Arcade Fire performing for La Blogothèque's Take Away Shows series

But Clermont-Ferrand is not only a public-facing festival nourishing voracious short-film lovers. On the business side, it remains the biggest short-film market in the world, filling the 1,000 square metres of an exhibition hall with representative bodies, short film agencies, production and distribution companies from all over the world, attending with the common intent of promoting their country’s short film production to international buyers and programmers.

On the upside, 2013 marked the return of a UK stand supported by the British Council – after two years of absence following the demise of the UK Film Council – as well as Lithuania’s first market attendance, a positive sign from a young country still establishing its film industry and international presence.

Despite these reasons to be cheerful, in the last couple of years the vitality of Clermont-Ferrand’s short-film market has undeniably been affected by the recession. While France continues to dominate, with broadcasters such as Arte and Canal+ still eager for shorts, other once-avid buyers such as the Portuguese channel RTP skipped the market for the first time in years due to threats to close their short-film slot. When I heard that in Germany arthouse cinemas get funded by the government if they commit to regular short-film screenings, I was left to conclude that the health of the short-film industry deeply reflects the geographical map of a Europe unevenly bruised and battered by the economic crisis and its crippling cuts to culture budgets.

And yet, even amidst the ever-changing scenarios of a film industry possibly at its most fragile and fluctuating, this year’s CFSFF once again demonstrated its precious role as a showcase of filmmaking talent at its rawest and most daring. At the end of another week’s immersion I was filled with optimism: all over the world, shorts never cease to excel in creativity, freedom, resourcefulness and the constant ability to reinvent their language and push boundaries despite the stifling dynamics of the film business.