One of early auteurism’s limitations was its emphasis on directors – Sam Fuller, Fritz Lang, Howard Hawks, Anthony Mann, John Ford – who were primarily associated with the male-dominated western, war and gangster genres, or who contributed to the noir cycle, in which femmes were usually fatale.

Of those American auteurs who privileged female characters, Vincente Minnelli, Max Ophuls and Douglas Sirk were often damned with faint praise, dismissed as empty stylists whose visual patterns were merely decorative. And when it came to the more classically restrained George Cukor, the assumption seems to have been that he wasn’t an auteur at all, that his oeuvre contained nothing in the way of a consistently pursued vision, and was thematically vacuous.

Since most of the original auteurists were themselves male, they were generally drawn to explorations of masculine themes: the building of the west, the horrors of war, the limitations of the traditional heroic role. But their lack of interest in undertaking thematic (as opposed to stylistic) readings of Minnelli, Sirk, Ophuls and Cukor suggests an inability to comprehend how these directors were concerned with the oppression of women within a patriarchal culture. The problem wasn’t that auteurist critics believed such a theme to be uninteresting or trivial, but rather that they didn’t perceive it as a theme at all.

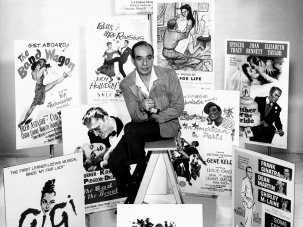

Today, after several decades of feminism, we are somewhat better positioned to understand those Hollywood masterpieces made by female-identified (and in many cases gay) filmmakers. Yet Cukor is still regarded as a relatively minor figure. His highest rated title in Sight & Sound’s last Greatest Films of All Time poll was A Star is Born (1954), which came 447th!

Not a single person voted for the other film Cukor made in 1954, It Should Happen to You. Yet, watching this gem again recently, it struck me as both a model example of how radical ideas can be explored within a popular format, and one of those fascinating works whose distinction is in part the result of an artistic conflict.

It Should Happen to You (1954)

It Should Happen to You’s protagonist is Gladys Glover (Judy Holliday, appearing for the fifth and final time under Cukor’s direction), a model who, after losing her job, decides to hire a billboard in New York’s Columbus Circle and have her name painted on it, thus making herself briefly famous. The film’s critique of Gladys’ behaviour connects with modern ideas about the superficiality of celebrity culture (see, for example, the Roberto Benigni sections of Woody Allen’s To Rome with Love), and is almost certainly the contribution of screenwriter Garson Kanin.

But what Cukor does with this theme is quite different from, and in certain instances directly opposed to, the ambitions of his writer. For if Kanin equates Gladys’ project with the pursuit of vacuous stardom, Cukor sees her need for recognition as the expression of a desire for sexual autonomy.

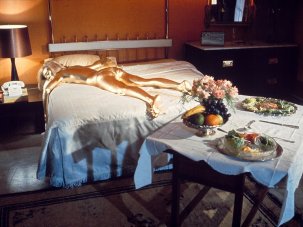

The link between the billboard and Gladys’ sexuality is remarkably explicit: while watching two painters preparing her sign, Gladys breathlessly chants “Faster, please, faster,” and later makes executive Evan Adams (Peter Lawford) drive her repeatedly around Columbus Circle so she can view the billboard (“What I’ve got that you want”), eventually admitting: “Every time I see it I get a bigger one than last time. Boot!” The sign is Gladys’ sexuality proudly displayed and publicly asserted, and if Kanin mocks both Gladys and the culture she represents, Cukor is generally approving of his heroine’s behaviour.

It Should Happen to You (1954)

The key character in terms of the director’s dispute with his screenwriter is Pete Sheppard (Jack Lemmon, here making his screen debut). It seems reasonable to assume that Pete is Garson Kanin’s stand-in. He articulates all the cliches about the joy of conformity, of being part of the crowd, that one might superficially take to be It Should Happen to You’s ‘message’: according to François Truffaut, “the moral of the story is that it is easier to find glory than to justify it.”

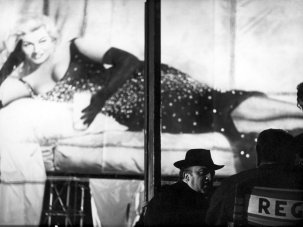

Yet Cukor’s mise en scène consistently undermines Pete, defining him as the mirror image of his romantic/ideological rival, the casual seducer Adams. From his initial appearance, Pete is associated with control of the look. He is introduced filming in Central Park, and encounters Gladys while shooting her arguing with a man who assumes she’s trying to pick him up (and who angrily informs her, “I like to do the picking!”).

Pete’s camera is the first in a series of photographic devices that end up being trained on Gladys by males who are determined to turn her sexuality into a commercial product, pursuing in the public sphere the same project Pete undertakes in the private one. As usual, Cukor makes a precise visual distinction between male and female spaces, with Pete’s apartment, which is full of filmmaking equipment, being the domestic equivalent of those offices and boardrooms wherein Gladys appears as a lost and isolated figure.

It Should Happen to You (1954)

It is significant that Gladys’ billboard displays her name, not her picture, the subsequent process by which she becomes an object for the male gaze (see especially the moment in which the soldiers she is posing with are ordered to look at her) representing an attempt to recuperate her assertion of sexual autonomy by turning it into something that can be packaged and sold. The impression that Gladys’ pursuit of fame is, in its original form, a legitimate protest against masculine control is reinforced by Cukor’s treatment of her appearance on a television talk show, where she is one of four female panellists dominating the conversation, much of the scene’s humour deriving from the single male guest’s frustrated attempts to complete a sentence.

The final scene, added against Kanin’s wishes, shows Gladys, now married to Pete, staring longingly at a roadside billboard with the words “space to rent” written on it. Pete may have convinced Gladys to give up her celebrity/autonomy, but Cukor makes it clear that, although the proprieties have been observed, Gladys’ sexuality will not be contained within the boundaries of a respectable marriage.

Kanin regarded this ending as a disaster, but it’s worth remembering that artistic conflicts are always traceable to ideological conflicts. In this case, the ‘betrayal’ of a heterosexual writer’s ‘vision’ by a homosexual director has resulted in a work whose conclusion shows assertive femininity triumphing over controlling masculinity.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.