“Money is everywhere but so is poetry. What we lack are the poets.”

— Federico Fellini

As part of Italy’s Entrepreneurial Culture Week last November, the national film school hosted a screening at its Milan branch to commemorate the 20th anniversary of Federico Fellini’s death in a singular fashion: with his commercials. Gathering together the strands of Italy’s metastatic triad of decline – governmental parasites, the intellectual mafia and (post-)industrial favouritism – the event regaled audiences with overlong, ego-driven speeches thankfully interrupted by the commercials Fellini did for Campari, Barilla and Bank of Rome.

From 1983 to 1992, the gentle giant of post-war Italian cinema flirted with corporate fairytales on more than one occasion. In 1983, he lent his endorsement, along with stylists Gianfranco Ferré and Krizia, the revered novelist Alberto Moravia and other prestigious celebrities, to the advertising of the women’s magazine Amica. And the following year he found his first commercial muse in the form of Campari, the fashionable red fluid with the immaculate label.

Featuring the production design of Dante Ferretti (Gangs of New York, Sweeney Todd, Hugo), the film stars a familiar member of Fellini’s entourage, Victor Poletti, along with a bored, very 80s-looking blonde. Set on a train compartment whose window works very much like a television screen, where sights can be changed at a remote control’s will, the ad bears the clear though somewhat restrained signature of the maestro. Scored by Nicola Piovani (Life is Beautiful, Dear Diary) and titled Che bel paesaggio (What a Nice Landscape), the ad’s tagline is “a modern fairytale”:

As his mercantile liaison with advertising tentatively developed, Fellini started working on Ginger and Fred, which was released in 1986. The film reunites two pillars of Fellini’s cinema and life, Marcello Mastroianni and Giulietta Masina, playing ageing performers reunited after several decades to perform their old act (imitating Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers) on a tacky TV variety show. Through the backstage of this fictional TV show we get a glimpse of the colourful and idiotic decay that Berlusconi’s channels were broadcasting in the 80s to jubilant audiences – decay to which, despite their astonished incredulity and mild indignation, the two old actors eventually surrender, for money.

A not-so-veiled critique of the cultural debasement private television channels both embodied and propagated through the ether, the film was to be interrupted by fake commercials Fellini himself had shot for the purpose. With the exception of one, featuring a voluptuous lady advertising olive oil via her swinging bottom, they did not make the final cut but were eventually retrieved and put together in the posthumous feature La Tivú di Fellini (Fellini’s TV, 2003) assembled by the Italian film critic Tatti Sanguinetti. In these bogus ads, Fellini pokes fun at the inherent predictability of consumer narratives, pushing their congenital deficiencies to hilarious extents.

Less than seduced by the financial benefits of advertising, the Italian director launched a campaign against films being interrupted by commercials on TV, to his mind a sacrilegious and uncivilised act. Alas consumer democracy, with its vaunted ‘freedom of choice’, put a very (un)happy ending to what probably was the director’s first and last foray into ‘politics’. Though his campaign gathered the support of many directors outraged by the way their films were being chopped up, when it was put down to audiences with a referendum viewers opted for the ad-filled treatment.

Meanwhile Barilla, the famous pasta brand, persuaded the director to direct a commercial for them. Here the maitre d’ of a refined restaurant goes through the finest (French) offerings on the menu but is suavely asked for a plain pasta dish, which, as the whole restaurant reminds us, can only be Barilla:

This commercial was presented during the event along with a curious ‘making of’ consisting of an audio track where Fellini can be heard directing the actors and sarcastically musing at one point: “If I was Mr Barilla I would sell the establishment off.” Funnily enough the brand was recently at the centre of a media storm when its CEO declared that his company would never produce a gay-friendly advertisement.

Far from over, Fellini’s adventures in consumerville were to be the last thing he did behind a camera. In 1992, the year before his death, he realised his best corporate work, a series of ads for the Bank of Rome. Here Fellini comprehended, skilfully conveyed and exposed the ultimate essence of advertising: the creation of needs and fears that the given product will magically solve.

A middle-aged man (La Voce Della Luna’s lead and Italian cinema icon Paolo Villaggio) keeps having nightmares that he relates with concern to his shrink (Buñuel’s alter ego Fernando Ray), who reassures him that he will take care of his psychological problems – and for all the rest, he can rely on the Bank of Rome. Watched today, the commercial acquires an almost paradoxical flavour given the level of trust banks now inspire, yet it remains an evocative piece of advertising that simultaneously promotes and unmasks the quintessential mendacity that every commercial sells:

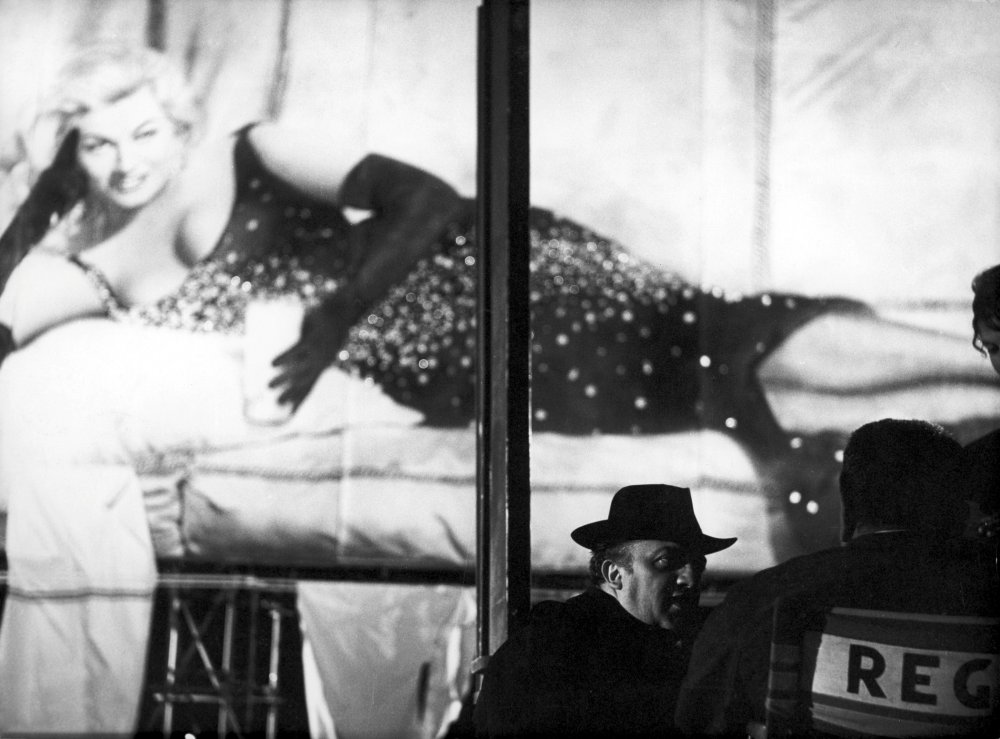

You can trace Fellini’s peculiar relationship with advertising back to 1962: in his contribution to that year’s omnibus film Boccaccio 70, the main character is actually a billboard. Camping on that billboard are Anita Ekberg and her generous breasts advertising milk. A petty grey man wants to have the billboard censored due to what he believes to be a lascivious pose, so Ms Ekberg comes to life in the night to provoke the man’s bigotry and his hypocritical outrage – almost as if, having captured the vapid aimlessness of the new celebrity-driven religion in La Dolce Vita, the maestro was now poking fun at the moralist outrage it had caused in certain sectors of a still very catholic society.

The god-fearing fella vs. the sensual deity. There it was, Fellini’s first commercial: an ode to beauty ridiculing the pretence of virtue.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.