Web exclusive

Although there has long been an intimate connection between literature and cinema, it is widely assumed the traffic can only legitimately move in one direction. Books are so frequently turned into films that the process has come to seem inevitable. I published my first novel, a work of dystopian science fiction entitled The Hunt, earlier this year, and without doubt the question I’ve been asked most frequently is when or if it will be adapted for the cinema.

There is no logical reason why novels should not be based on films, rather than vice versa, yet those that are tend to be dismissively labelled ‘novelisations’. At one point in Woody Allen’s Manhattan (1979), Mary (Diane Keaton) is asked by Isaac (Allen) why she’s wasting her time writing one. Mary’s response – “Because it’s easy and it pays well” – prompts an angry outburst from Isaac, who describes novelisations as “another contemporary American phenomenon that’s truly moronic.”

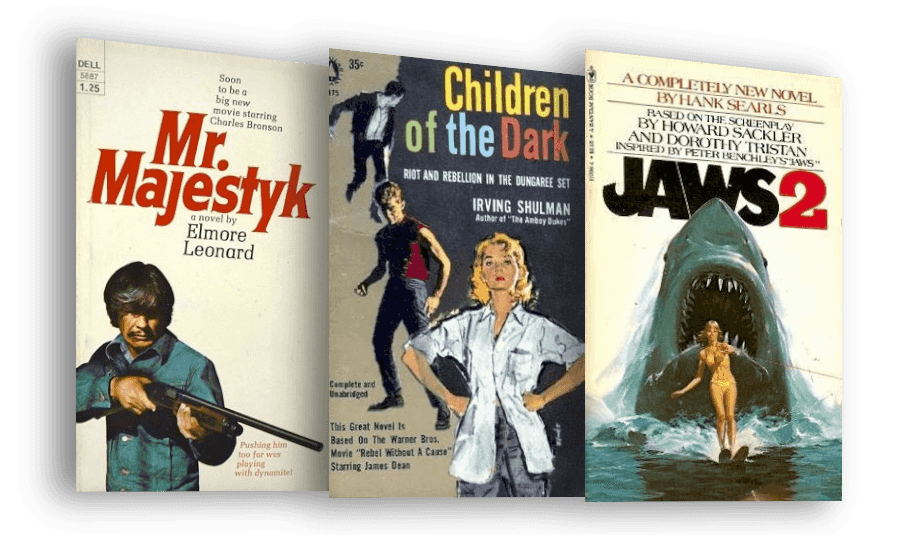

The reasons for this attitude can be traced to the purely commercial circumstances under which such books are created: authors do not get burning desires to write them, instead being commissioned to do so. Yet many novelisations are the creations of screenwriters. Elmore Leonard, for example, turned his screenplay for Richard Fleischer’s Mr. Majestyk (1974) into a book which is still in print, and is undoubtedly enjoyed by admirers of the author who do not realise they are reading a novelisation.

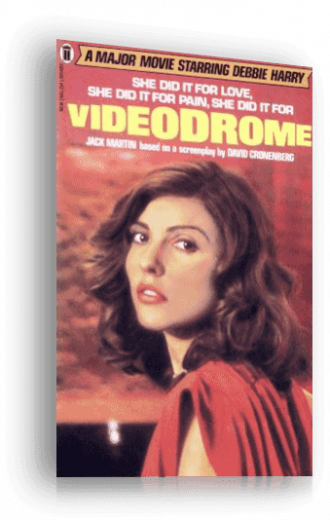

Novelisations often provide us with access to excised material. Dennis Etchison’s novelisation of Videodrome (1983), written under the pseudonym ‘Jack Martin’, contains some fascinating dialogue derived from director David Cronenberg’s earlier screenplay drafts.

There are also a number of unclassifiable oddities:

- Hank Searls’ Jaws 2 (1978): based on a screenplay by Howard Sackler and Dorothy Tristan, which was to have been directed by Tristan’s husband, John D. Hancock. It bears little resemblance to the film eventually made by Jeannot Szwarc from a screenplay by Carl Gottlieb.

- Irving Shulman’s Children of the Dark, based on the author’s unused draft for the film that became Rebel Without a Cause (1955).

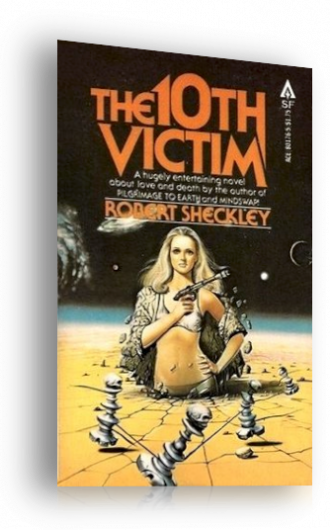

- Robert Sheckley’s The Tenth Victim (1965), the novelisation of a film written and directed by Elio Petri, which was itself based on Sheckley’s short story The Seventh Victim. Sheckley went on to write two sequels.

- Dean Koontz’s The Funhouse (1981), the first two thirds of which are actually a prequel to the film made by Tobe Hooper from a screenplay by Lawrence Block.

- Ray Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes, which started out as a short story entitled The Black Ferris in 1948, was turned into a treatment for a movie to be directed by Gene Kelly in 1955, became a novel published in 1962, and was eventually filmed by Jack Clayton, from a screenplay by Bradbury, in 1983.

Then there’s Alan Sharp, a Scottish novelist who attracted serious critical attention for his first two books, A Green Tree in Gedde (1965) and The Wind Shifts (1967), before becoming a Hollywood screenwriter. Sharp found his way back into novel-writing by penning novelisations for two of the films he wrote, Peter Fonda’s The Hired Hand (1971) and Arthur Penn’s Night Moves (1975), in both cases incorporating material that never made it to the screen. In Night Moves, Harry Moseby (Gene Hackman) turns down the opportunity to see Ma nuit chez Maud (1969), describing the experience of watching an Eric Rohmer film as “like watching paint dry.” In Sharp’s screenplay, however, the filmmaker Moseby refers to is Claude Chabrol, a preference also reflected in the novelisation, the film Moseby avoids there being Le Boucher (1970).

Sharp is hardly the only screenwriter to set the record straight by returning to drafts subsequently reworked by other hands:

- Leonard Schrader’s screenplay for The Yakuza (1974) was slightly revised by his brother Paul, then extensively rewritten by Robert Towne at the insistence of director Sydney Pollack, but the tie-in paperback lets us experience Schrader’s narrative in its initial form.

- Arthur Laurents’ novelisation of The Way We Were (1973), another Sydney Pollack movie, restores several crucial scenes eliminated at the director’s insistence.

- Earl Mac Rauch’s New York, New York (1977) is strikingly different from Martin Scorsese’s film (rewritten by Mardik Martin), including a protagonist with a different name (Johnny Boyle rather than Jimmy Doyle).

Less known is W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings (1975), whose novelisation by screenwriter Thomas Rickman has been championed by Quentin Tarantino. As Tarantino told Brian Helgeland:

“Thomas Rickman was so disgusted with what they did with his movie that he asked to write the novelisation, so that one person out there would know what it was that he intended. I’m 40 now, and I still read W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings every three years. I’m that one person.

When I saw the movie, though, a few years after I’d first read the book, I was like, What the hell is this? I mean, I was offended. I was literally offended. The novelisation was pure. But this was Hollywood garbage. So that’s why I started writing screenplays, because I was so outraged.”

Although W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings, directed by John G. Avildsen, has become extremely difficult to see, a transfer recently appeared on YouTube. Comparison with the novelisation reveals that many of Rickman’s scenes were cut or rewritten, W.W. (Burt Reynolds)’s speech about serving in Korea being a notable addition. A screenplay draft dated 28 June 1973 bears the legend “revised by Frank R. Pierson”.

Given Tarantino’s comments, one passage stands out. Early in the film, W.W. attends a drive-in with a female companion, who upbraids him for ignoring her in order to watch Errol Flynn in The Sun Also Rises (1957), which is playing on the drive-in screen. When the woman asks W.W. if he is “queer or something”, W.W. responds, “No. But if I ever turn queer, that’s the guy I’d wanna turn queer for.”

This is surely the source of Clarence’s speech at the start of True Romance, one of Tarantino’s earliest screenplays:

“I’m no fag, but Elvis was good-lookin’. He was fuckin’ prettier than most women. I always said if I ever had to fuck a guy… I mean had to ‘cause my life depended on it… I’d fuck Elvis.”

Elvis Presley is a pervasive presence in W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings, parts of which take place in a Nashville bar where Elvis impersonators perform. But W.W.’s dialogue about turning queer does not appear in Rickman’s novelisation (in which the drive-in movie is The Robe), and was presumably the creation of uncredited co-screenwriter Pierson. Although Tarantino claims to have started writing screenplays because of his outrage at the changes made to Rickman’s original draft of W.W., these changes directly inspired one of his most frequently quoted monologues. In the battle between art and commerce, things are not always as clear as they initially seem.

W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings (1975)

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.