from our April 2013 issue

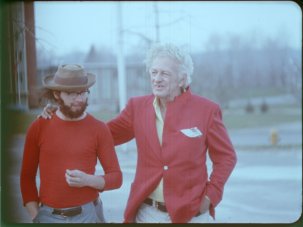

Now shooting: Monte Hellman filmed material for ‘Shatter’, which was credited to Michael Carreras

Near the beginning of Shatter (aka Call Him Mr Shatter, 1974), which is credited to Michael Carreras, the eponymous protagonist (Stuart Whitman) enters a hotel room in which the president of an East African state is embracing a young woman. Shatter is holding a camera, apparently to take blackmail photos; but it is actually a cunningly disguised gun, which he uses to assassinate the politician.

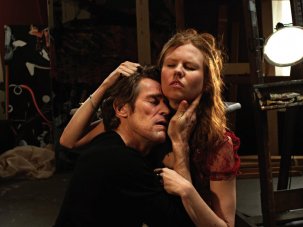

Thirty-six years later, towards the end of Monte Hellman’s Road to Nowhere (2010), filmmaker Mitchell Haven (Tygh Runyan) finds himself in a hotel room with a pair of corpses. As the police arrive outside, Haven begins filming their activities through a window: unable to see what Haven is pointing at them, a cop orders him to “drop the weapon”. The concern these two films share with the idea of a camera as a weapon is hardly coincidental, since the Shatter scene was in fact directed by Hellman, whom Carreras replaced half-way through the production and whose name does not appear on release prints.

The original auteurists prided themselves on their democratic tendencies, claiming that the tastes of mass audiences were generally superior to those of ‘professional’ critics, who preferred Zinnemann, Stevens and Wyler to Hawks, Hitchcock and Boetticher. But in its insistence on looking for ‘clues’ to the interpretation of one film in other films by the same director, auteurism is also a form of connoisseurship. With films that involve uncredited co-directors, this version of la politique des auteurs makes some of its loftiest claims, asserting the ability to crack a code within a code.

When great directors contribute anonymously to the work of hacks, or vice versa, the situation is relatively straightforward: nobody will have trouble picking out the scenes Erich von Stroheim shot for Merry-Go-Round (1922) before Rupert Julian took over, and those parts of Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil (1958) added by Harry Keller stick out like sore thumbs. Cases in which the credited and uncredited directors are both illustrious can be more problematic, but also more fascinating.

Auteurism locates some of its loftiest claims in the ability to identify the hand of one director in work credited to another

The opening section of Spartacus (1960), directed by Anthony Mann before he was fired, is stylistically quite distinct from, but neither inferior nor superior to, Stanley Kubrick’s footage. Or take Macao (1952), which, despite being credited solely to Josef von Sternberg, was substantially reshot by Nicholas Ray, who ended up being responsible for approximately one third of the final version.

It’s difficult to think of two filmmakers whose approaches were more irreconcilable. Von Sternberg privileged image over performance and was interested in his actors solely to the extent that he could interrogate their publicly mediated identities. Ray privileged performance over image and related to his actors as human beings, teasing out the ‘genuine’ person concealed behind the ‘fake’ persona: the Humphrey Bogart of In a Lonely Place (1950), the James Cagney of Run for Cover (1954), the Richard Burton of Bitter Victory (1957) and the Charlton Heston of 55 Days at Peking (1963).

Of course, in reshooting Macao, Ray would not have been consciously attempting to impose his own personality; on the contrary, he was clearly trying to imitate von Sternberg’s approach. Much of the film’s peculiar charm is due to Ray’s inadequacies as a cold-blooded professional, his humanist affection for Robert Mitchum and Jane Russell constantly distracting him from the job at hand. This is especially evident in the sampan scene, which contains some wonderfully spontaneous gestures (notice Russell’s amusement as Mitchum offers her his right hand when she has obviously been expecting his left), a sense of vulnerability (Mitchum’s confession that he has “been lonely in Times Square on New Year’s Eve”) and an emphasis on unironic intimacy that, for better or worse, are incompatible with von Sternberg’s worldview.

Road to Nowhere (2010)

Uncredited work is generally given a strictly subordinate role in discussions of a particular director, but this might not be fair. Raymond Durgnat’s 1974 book Jean Renoir contains chapters on each of Renoir’s shorts and features, but only refers in passing to the director having “discussed the possibility of a film starring Deanna Durbin”. In his autobiography, Renoir doesn’t mention this project at all.

But the Durbin film was actually made. Shot in 1942 as Forever Yours, it was released in 1943 as The Amazing Mrs. Holliday, attributed to producer Bruce Manning (his only directorial credit), who had amicably taken over from Renoir. In a letter to William K. Everson, published in the August 1987 issue of Films in Review, Durbin insisted that “Jean Renoir shot two thirds of the film as it now stands.”

Mrs. Holliday is, at least for its first hour, far more Renoirian than his previous film Swamp Water (1941), parts of which were directed by Irving Pichel. As in La Régle du jeu (1939), the problem of obeying or even comprehending rules – initially those of America’s immigration authorities, later those of San Francisco’s high society – is a key theme, beautifully illustrated by Durbin’s character’s difficulty negotiating the spaces of a luxurious house, her naturalness clashing with the artificially imposed requirements that she wear high heels (in which she can barely walk) or use a particular spoon (with which she cannot eat). There’s something Boudu-like about Durbin’s character, particularly in two dinner-table scenes during which she shocks the butler by picking up food with her hand and walks from one end of the table to the other to facilitate conversation. Despite its bland final section, The Amazing Mrs. Holliday strikes me as one of the finest and most characteristic examples of (to use Durgnat’s term) Renoir Américain.

The Writers Guild of America successfully campaigned to have blacklisted writers’ names added to the credits of several films. Perhaps it’s time the Directors Guild suggested that unacknowledged directors be treated similarly, enabling the recognition of some unjustly neglected gems.

-

Sight & Sound: the April 2013 issue

In this issue: Danny Boyle, Kristin Scott Thomas, Carlos Reygadas, Point Blank and Beyond the Hills.