Web exclusive

In his introduction to the awards ceremony of the 19th BAF, Barry Purves playfully – but pointedly – mocked a recent blog post by the Guardian’s David Cox, which dismissed the revival of stop-motion animation in features such as Tim Burton’s Frankenweenie (2012) as “an affectation of the digital-disdaining classes”.

19th Bradford Animation Festival

Bradford, UK | 13-17 November 2012

It’s perhaps unsurprising that Barry – one of the finest stop-motion animators the world has ever seen – was somewhat piqued to find his metier branded “a low-rent option” that has failed to evolve for over 100 years. But even for those less implicated in the process, the screenings and events at this year’s festival were more than enough to prove such opinions, in both technical and aesthetic terms, absolute nonsense.

Award-winning British filmmaker Robert Morgan has given audiences across the globe an emotional pummelling with a series of increasingly unnerving and provocative stop-motion films. In a talk accompanying a retrospective of his work, he explained how he begins by sculpting his main character, even before the script idea is fully formed in his mind. With the blotchy, rabbit-eared thug at the centre of Bobby Yeah (2011), this was to be the start of a creative relationship of the most personal kind, for the artist and his creation were to live together in Morgan’s spare bedroom for the next three years, provoking each other into equally tempestuous performances.

Bobby Yeah

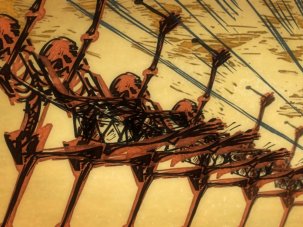

Even on big budget stop-motion films, the relationship between an animator, the characters and their environment can be remarkably intense. In a presentation on the making of The Pirates! In an Adventure with Scientists (2012), Aardman animator Will Becher described how for over a year the Pirate Captain’s office became Becher’s own – a familiar place of work with all its quirks and foibles – despite the fact that he could only peer over the top, and poke his hands through the sides.

Comparisons of stop-motion and CGI often concentrate on their looks, when the differences are more fundamental. Pre-production phases on animated features, whatever the chosen form, are actually remarkably similar – scripting, storyboards, characters design all follow a similar path. It’s when it comes to the building of worlds that they require different crafts.

I fully appreciate the skill and effort that goes into creating an object in a virtual environment that seems to have weight and presence – that catches the light and casts a shadow. But I also love the fact that Aardman contracted a local glassblower to produce hundreds of tiny glasses for their characters to pick up and toast with. Computer animation can create imagery of increasingly complex realism, but it could never feature a character’s head fabricated from a year’s worth of the filmmaker’s own toenails (as in Bobby Yeah). An animator will work differently with a stuffed cat he’s personally selected from the back of a taxidermist’s van and fitted with a steel armature, as Morgan did for 2001’s The Cat with Hands, than he or she would manipulating a computer mouse:

Watch the extract at the top of the page from Pixar animator Carlo Vogele’s Una Furtima Lagrima – a film in which a real dead fish sings its own requiem on the way to the frying pan, which won BAF’s Short Shorts award – and tell me it would be a tenth as effective in CGI.

David Cox argued stop motion had evolved little since its supposed debut in Humpty Dumpty’s Circus in 1897 – a date likely gleaned from Wikipedia, which cites the same example. In fact that now-lost film was probably made around 1908 (as the IMDb has it); the earliest extant example of true stop-motion I’ve seen are the animated title letters on 1905’s How Jones Lost His Roll:

It’s true that the only technical advance separating the animation of Arthur Melbourne-Cooper’s 1908 mini-masterpiece Dreams of Toyland (above) from 2011’s Herdy Heads for the Hills is the invention of Blu-tack – vital for holding a herd of porcelain sheep in place as they cross the windy Lake District. Not that this seemed to matter to BAF’s judges, who awarded Herdy Best Commercial ahead of a host of other more cutting-edge efforts:

Still, the idea that stop-motion has not moved on technically is another example of perhaps wilful ignorance. 3D printing technology has enabled animators to perfect the replacement technique developed particularly by George Pal in the 1930s. LAIKA’s Mark Shapiro gave a talk on the making of ParaNorman (2012), revealing how thousands of unique facial expressions for their characters could be modelled in a computer environment and then printed as 3D objects and snapped into place on the characters’ heads. Aardman used the same technique for the lower jaw of the characters in of The Pirates! In an Adventure with Scientists.

Computer animation is not here to replace stop-motion as a technique, but it is another valuable tool in the animation armoury. Comparisons that fail to peek below mainstream feature production to the hundreds of independent short and long-form works that populate animation festivals across the globe each year will never fully appreciate the quirks and benefits of each technique.

Oh Willy

But for those in any doubt of the validity of stop-motion as a medium should track down Emma De Swaef and Marc James Roels’ Oh Willy (2012; trailer; homepage), winner of the Best Professional Film at BAF – testament to the unique emotional rapport stop-motion can create with an audience. It follows an overweight middle-aged man who returns to the nudist camp where he lived as a child to see his ailing mother. From there, “Willy bungles his way into noble savagery”, in the words of the producers, and we follow his journey through a world made of fabrics and felts to an astonishing end.

Of course it’s not just stop-motion that makes this a great film. But the ‘wind’ whistling through Willy’s threadbare ginger hair, or the nap of the felt on the character’s face boiling under the repeated touches of the animator’s fingers, are both essential parts of why the film lifts your heart.