Here’s the question it’s hard to get around when discussing Lav Diaz’s latest film A Lullaby to the Sorrowful Mystery. What does it actually mean to watch an eight-hour movie?

Philippines / Singapore 2016

485 min

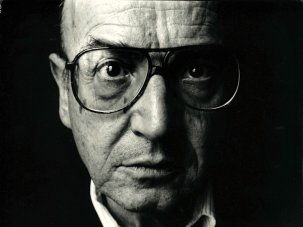

Director Lav Diaz

Cast

Simoun Piolo Pascual

Isagani John Lloyd Cruz

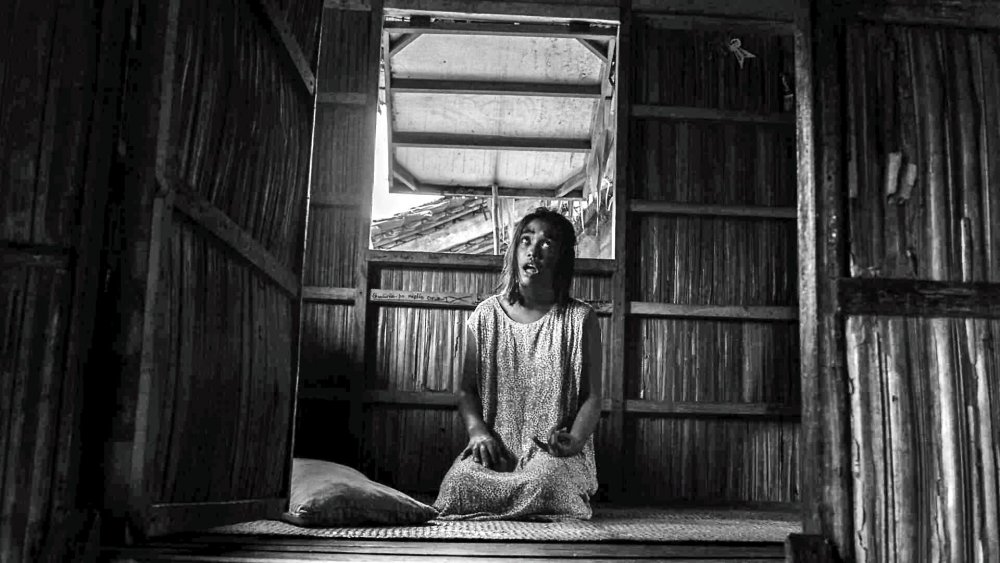

Oryang / Gregoria De Jesus Hazel Orencio

Cesaria Belarmino Alessandra De Rossi

Mang Karyo Joel Saracho

In Tagalog, Spanish, English

► Trailer

In the context of any film festival, it means blocking out a stretch of time in the schedule, making a decision to watch this film rather than three or possibly four others, and reprogramming your receptivity – which in festivals, is attuned to a rhythm of high-intensity omnivorousness – to a different pitch and very different demands. It may be something to do with general fatigue at the end of the Berlinale (Diaz’s film played on the final Thursday), or it may be a side-effect of the dressing on the salad I grabbed in the hour-long halfway intermission; the fact is that, dozing off somewhere in the film’s fifth hour, I actually started to hallucinate, or at least to wildly misread the images on screen. And I can’t believe that the already hypnotic nature of the no doubt aptly named Lullaby doesn’t have something to do with that.

The Filipino director himself commented at his Berlin press conference that it was misleading to dwell on the lengths of his films. “We’re labelled ‘the slow cinema’. But it’s not slow cinema, it’s cinema. I don’t know why… every time we discourse on cinema we always focus on the length.

“It’s cinema, it’s just like poetry, just like music, just like painting where it’s free, whether it’s a small canvas or it’s a big canvas, it’s the same… So cinema shouldn’t be imposed on.”

But not to talk about the length of Diaz’s films would be like pretending that the size of Anselm Kiefer’s paintings was of no consequence: when an artist chooses a canvas, whether it’s to be covered in paint or flickering shadows, its expanse is part of the means of expression. Besides, Diaz chooses to make very long films not as exceptions, but as his standard practice: duration, and his way of engaging the viewer’s floating attention over long stretches of often confusingly complex narrative, are central components of his artistic arsenal.

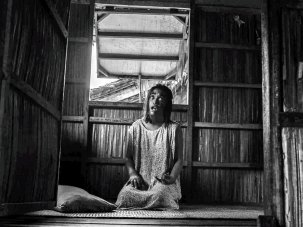

A Lullaby to the Sorrowful Mystery (Hele Sa Hiwagang Hapis, 2016)

The problem, though, is that it’s very hard to get a clear critical perspective on any given Diaz film, because whenever you see one, it imposes its own singularity and its own anomalous demands on you. Sometimes the very fact of getting all the way through an exceptionally long film can numb the critical faculties, make it harder to go into things in any analytical depth.

For one thing, even though I’ve become used over the years to taking attentive, detailed notes during movies, it’s not something that’s easy to sustain for eight hours, retaining (even noticing) all the salient details. For another, unless you’re a very assiduous festival-goer who always manages to be in the right place at the right time, it’s remarkably hard to become any sort of Diaz specialist – and I’m certainly not one.

My first exposure to his cinema was when Melancholia (2008) screened as part of a ‘Slow Cinema’ weekend at Tyneside’s AV Festival in 2012. I can honestly say that its leisurely unfolding of a multi-stranded, byzantine narrative that appeared to follow the unpredictable promptings of real-life contingency (e.g. characters disappearing because certain actors dropped out of the shoot halfway) seriously shook up the way I think about film narrative. Since then, I’ve seen his A Century of Birthing (2011), which I enjoyed somewhat less – and which for some reason, I find much harder to remember – and Norte, the End of History (2013), which at 5½ hours is commonly supposed to be one of Diaz’s ‘easy ones’, but which in any case, given its borrowings from Crime and Punishment, has a strong unifying narrative backbone that makes it considerably easier to watch.

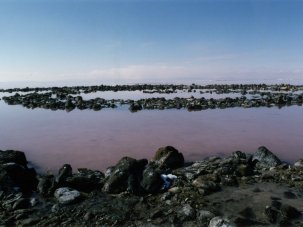

From What is Before (Mula Sa Kung Ano Ang Noon, 2014)

Since first filing a very brief, appreciative review of A Lullaby a few days ago, I’ve exchanged tweets with people who clearly know his earlier work, such as Death in the Land of Encantos (2007), as well as recent films like Florentina Hubaldo, CTE (2012) and From What Is Before, a multiple award-winner in Locarno in 2014. I wish I’d seen them; I hope I do before long.

Meanwhile, having to quickly turn over a short trade review of Lullaby means fulfilling some basic – you might say, frustratingly basic – requirements. You simply try to describe what it feels like, what it’s about, how it looks, how it differs from the other Diaz films you know. I won’t go into that great detail on Lullaby here either, partly because the sheer scale and complexity of the thing somewhat defuses my critical capacities – but I’m also very aware that the nature of an extremely long film makes it something like an elephant – different people find themselves focusing on the ears, the tail or the eyes, but most of us have to reconcile ourselves to not seeing the whole elephant in any great detail.

I felt that the film’s first half was hugely entertaining, with occasional leaps into non-sequitur comedy and supernatural farce actually making me laugh out loud on occasion; the second four hours, with its characters wandering sometimes very languidly around a vast forest, was more of a grind. By contrast, Guy Lodge tweeted that the film “picks up after 3 agonising hours”, and added, “A reminder, if you needed one, that all viewers watch the same movie, but no two of us see the same one.”

I probably would have been a lot more lost in Lullaby if Norte – with its lengthy philosophical and historical discussions between Manila intellectuals – hadn’t obliged me to do some Googling on the history of the Philippine Revolution against Spanish colonial forces (1896-97), and in particular the execution of revolutionary leader Andrés Bonifacio y de Castro. The latter is an episode which, judging by Diaz’s films, appears to resonate through Philippine historical consciousness (or his personal version of it) as the Napoleon legend once did through the European 19th-century novel.

At any rate, Bonifacio appears as a character in Lullaby, as does his spouse Gregoria de Jesus: one narrative strand involves her search for his body after his death. According to Diaz’s press notes, there are four strands to the film: the search undertaken by Gregoria, aka Oryang, played by Hazel Orencio (she’s not the only character to have more than one name); the story of the revolutionary ballad ‘Jocelynang Baliwag’ (if I understood right, it’s sung by a young idealistic musician who is killed in action early in the film); the travels of two friend-enemies, student Isagani and Byronic jeweller-turned-saboteur Simoun, aka Crisotomo Ibarra, both characters from the 1891 novel El filibusterismo by José Rizal (another revolutionary hero, whose own execution kickstarts the action); and finally, a search for mythical messianic hero Bernardo Carpio and the interventions of three half-human, half-horse figures, Filipino-folkloric tikbalangs, who provide sometimes sinister comic relief and basically function like the manipulating supernatural forces in certain Shakespeare plays. Given the generally dream-like mood of Shakespearean faery that dominates the film’s jungle-set second half, together with its propensity to skip abruptly between strands, you wonder that Diaz doesn’t occasionally flash up that famous stage direction, “In another part of the forest…”

A Lullaby to the Sorrowful Mystery (Hele Sa Hiwagang Hapis, 2016)

A Lullaby is a remarkably complex film, and navigating its rambling paths really is like hacking your way through dense foliage, occasionally arriving at a clearing where, to your surprise, you run into people that you hadn’t sighted for a couple of hours. The fact that Diaz here plays with so many registers – historical, political, metaphysical and the further dimension of fictional borrowing – makes A Lullaby about as multi-dimensional and allusive as a film can be.

How is a viewer supposed to handle all this, particularly one that knows nothing about Philippine history? Diaz doesn’t make it easy for us: the names, the references, the allusions to specific incidents such as the 1897 massacre at Silang, all come thick and fast, with seeming disregard for what we can actually absorb and make sense of.

Equally challenging is the way that the dialogue is often delivered in a sotto voce, incantatory tone which further lulls our ability to concentrate – although this is just one of the film’s performance registers. Another is the goofy, pantomimic playing of the three tikbalangs, headed by an elderly, top-hatted gent (Bernardo Bernardo) who occasionally snarls direct to camera, while all of them now and again comically prance and whinny as their horse selves emerge. Then there’s the outright melodramatic playing of the film’s Spanish commander, a veritably moustache-curling display of stage villainy.

Guy Lodge in his Variety review accuses Diaz of “stony, audience-opposed self-indulgence”, and it’s hard to argue with the last term. But then, imposing difficult terms of engagement on an audience, which viewers have the choice to accept or not (we can always walk out), is an uncompromising strategy which is absolutely anomalous in cinema, or indeed any art, today – although it was once a central possibility in the artistic experimentation of the 1960s and 70s. The nature of Diaz’s films is that they do overwhelm us, defying us either to submit to or to refuse their spell.

That in itself is a major problem, especially for critics: no one likes to find their acuity defused by a work’s vastness or entanglement. I feel I’ve already spent far too long simply describing Lullaby and getting across some simple impressions of why it’s at once perplexing, frustrating, enchanting and – yes, in stretches, I can’t deny – boring too.

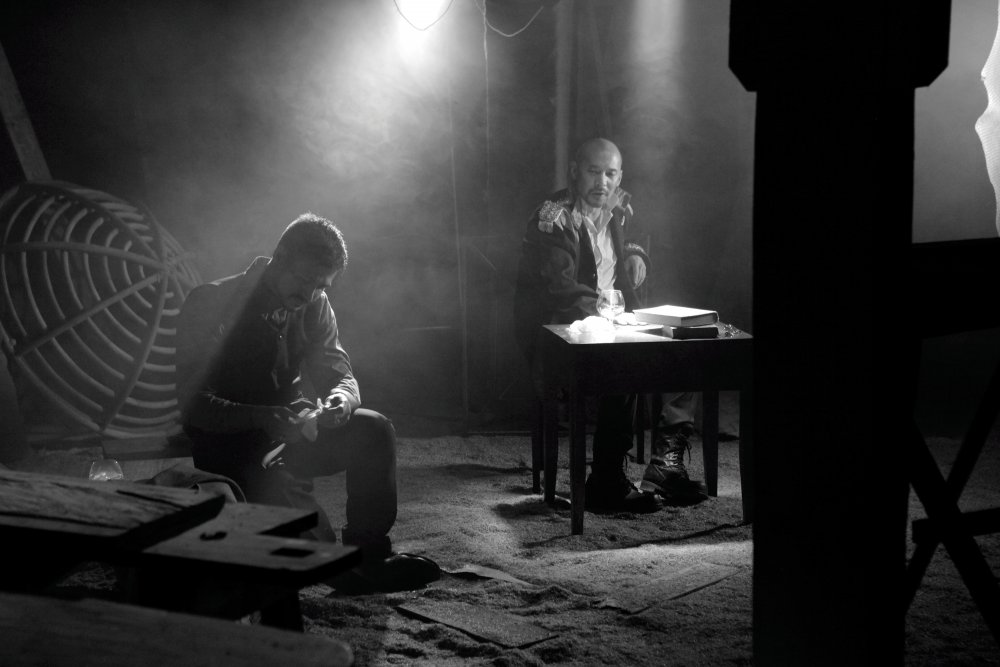

As for the “declamatory, didactic rhetoric” that Lodge disparages, I admit I found myself tuning out, but didn’t find it a problem. Largely featured in the scenes between Simoun (Piolo Pascual) and the Spanish general, and those between Simoun and Isagani (John Lloyd Cruz), and involving – with the benefit of 21st-century hindsight – questions of the destiny of the Filipino nation, these passages are without doubt rhetorically heightened, but they felt to me as if they had an appropriate place in Lullaby’s overall texture. They reinforce the film’s nature as a piece of multi-voiced modern political epic, or opera without words; many of us may tune out from them, but they are as integral to the whole as the political, philosophical or aesthetic discourses in Dostoevsky or Thomas Mann.

A Lullaby to the Sorrowful Mystery (Hele Sa Hiwagang Hapis, 2016)

Diaz doesn’t, after all, want his films to be easily digestible. And watching – really watching – an eight-hour film is as much a physical as a mental challenge. I’m not sure how much deeper I can go than to say that Diaz’s latest opera (mainly) without music is overwhelming, bewitching, perplexing – or that, for me, it was less satisfying than either Melancholia or Norte.

Can I explain why? Not in any great depth, I suspect. Still, each of his films is like a huge meteor dropped into any festival that shows it, and if you choose to examine it, you have to be prepared to be somewhat at a loss.

Would I have missed Lullaby, though? What do you think?

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.