Joanna Margaret Paul’s Bosshard Family (1976), restored by Mark Williams and shown as part of the BFI London Film Festival’s Experimenta strand

Credit: Mark Williams/CIRCUIT

Addressing gender inequality in the film industry and the creative sector more broadly, the BFI’s Chief Executive, Amanda Nevill, announced that 2015’s BFI London Film Festival would celebrate the “year of strong women”. Just as Sight & Sound magazine‘s pivotal ‘Female Gaze’ issue initiated a critical revaluation of women’s contributions to filmmaking history, the festival’s Opening Night Gala screening of Suffragette was unexpectedly plunged into the storm and stress of smoke bombs, as feminist protesters from a group calling itself Sisters Uncut, there to protest government funding cuts to domestic violence services and pay inequality, disrupted the ritual parade of tinsel by prostrating themselves on the red carpet.

Years before, in 1979, the moving image art world experienced its own moment of upheaval when, dismayed at what appeared to be attempts to frustrate their work, Lis Rhodes and Felicity Sparrow withdrew from the Hayward Gallery’s now legendary Film as Film exhibition and were instead spurred on to form Circles, an empowering women’s experimental film distribution network. So it was fitting that the Blue Room at BFI Southbank, situated in the former Museum of the Moving Image, which once faced opposite the Hayward, should be the site of a renewed critical dialogue, seeking to address the film-historical marginalisation of women of the avant-garde.

The platform for this timely and vital discussion, chaired by respected writer and curator Lucy Reynolds, was the Archive Talk event, a forum for exploring the process and ethics of artists’ film conservation embedded into the festival’s Experimenta strand. Experimenta’s hosting of two archival programmes of non-canonical women artist-filmmakers, from Argentina and New Zealand, being the catalyst for the seminar’s focus.

Both programmes revealed work that had never before been seen in this country, most of it, until recently, rarely seen in their own countries. Yet, while one of the programmes, of films by Marie-Louise Alemann, revealed an urbane, sophisticated and subtly political avant-garde sensibility from the Buenos Aires art world, the other, by Joanna Margaret Paul, showed the much simpler, observational and poetic beauty of a localised and bucolic domestic existence. It was this (and by contrast the much more self-consciously sophisticated responses to it by contemporary New Zealand artists) that formed the restoration case-study component of the talk by Mark Williams, director of CIRCUIT, an arts agency that supports artists working in the moving image through a range of initiatives, encompassing commissioning, distribution, critical review and professional practice.

Sandra Lahire's Serpent River (1989)

Credit: Courtesy of Maud Jacquin/LUX

Williams’s presentation focused on more traditional modes of bringing to light a previously unacknowledged (at least in this country) body of feminine practice. He emphasised the technical challenges of digitising the work and releasing DVDs and texts commemorating the project, arguably thereby reproducing a masculine analytical and technical approach, as suggested later in the discussion by one (male) questioner. Independent curator and writer Maud Jacquin and LUX collection manager Charlotte Procter, meanwhile, located their own surveys in the emergence of British women reclaiming the means to distribute and exhibit their work.

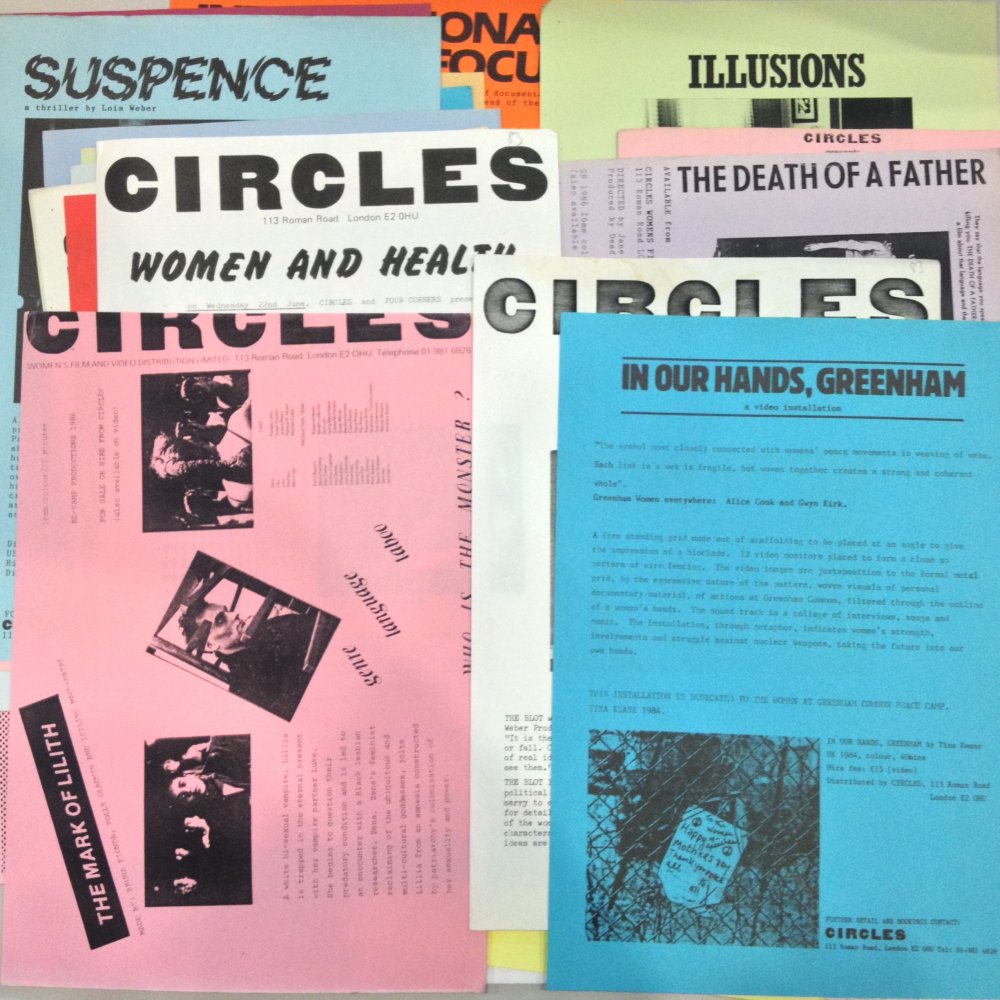

Emerging from the male-founded London Filmmakers’ Cooperative (which celebrates its 50th anniversary in 2016), from the late 1960s onwards, early UK women artist filmmakers such as Sally Potter, Annabel Nicolson and Marilyn Halford explored performance and the material and perceptual properties of film. Yet, by the end of the 70s, when the practice was at last gaining recognition in the mainstream art and film worlds, Rhodes’ revolt gave rise not only to the formation of Circles, but to a whole movement of UK independent feminist film distribution.

This would ultimately evolve – after a 1991 merger between Circles and political newsreel collective Cinema of Women – into Cinenova, a collective and distribution network whose productions are now being revisited and progressively digitised by a working group, which includes Procter (a firm believer in ‘distribution as preservation’). It’s an ethos that maintains screening films, and thus disseminating their understanding, as a better method of preserving them than their being withheld from view for years of delicate conservation work.

A selection of Circles publicity material from the Cinenova collection

Following the speaker presentations, a lively and highly engaged Q&A ensued. Helped by the presence in the audience of many former members of the collectives, the discussion ranged from the under-acknowledged history of feminist video art collectives to writing film descriptions as a more economical method of distribution. Also raised was the idea that the perpetuation of the notion of the lone artist as a heroic (and predominantly masculine) auteur was perhaps a counterproductive model for a feminist alternative that might otherwise flourish within collectivised modes of practice.

Reynolds concluded the discussion with a commentary on the need for women working within an experimental context to be better integrated into moving image discourse, urging all present to “keep moving those histories into the present moment”.