Web exclusive

Wounded (La Herida)

Crisis. That word could quite easily have been a contender for one of the ‘experiential pathways’ that now structure the new-look BFI London Film Festival programme. It’s certainly the subject of many a Spanish film showing at the 2013 edition of the festival; ‘crisis’ in regard to not so much the financial hardships that have been such a common feature of Western economies for some years now, but rather the personal and social consequences they trail in their wake.

One such consequence is the tendency to generalise and impose artificial categories and boundaries (such as the division between northern and southern Europe), which inevitably erase the defining intricacies of a country’s specific circumstances. It’s a bit like the eternal tug-of-war between commercial mainstream cinema and that largely meaningless, diminishing banner draped over anything different – the so-called alternative cinema.

In the case of Spanish cinema, alternative ways of producing and distributing films, brought into being by the crisis, have united an otherwise eclectic group of filmmakers. They don’t so much follow in the steps of by now established international figures such as José Luis Guerín, Albert Serra, Isaki Lacuesta and Javier Rebollo, but rather share a common enemy.

Both Lacuesta and Rebollo are active members of a collective called Cineastas contra la Orden (Filmmakers Against the Law), together with old sea-dog Fernando Trueba (Belle Epoque, Chico & Rita) and producer Luis Miñarro amongst others. The organisation was formed in response to a change in state film funding, which grants cinema a larger overall budget, but shared out among far fewer, so-called ‘quality’ films – a situation that has left many of the smaller, more experimental films practically bereft of state money.

The Fear (La por)

Yet in spite of such shortsightedness, the films that have emerged in the last few years outside the rigid confines of Spanish commercial cinema are good enough to have inspired this month’s issue of the specialised Spanish film magazine Caimán Cuadernos de Cine (formerly Cahier España). Even the British press has picked up on this recent upsurge – a Guardian article was headlined “Spanish film-makers hit back at ‘cultural war’ on funding”. The piece focused on the destructive impact of ‘draconian’ new cuts (a further 9 per cent) imposed by the Spanish government for 2014, fearing this will mark the end of the ‘other’ Spanish cinema.

Some game-changing titles from the last couple of years – such as Carlos Vermut’s Diamond Flash (2011) and Paco León’s Carmina o revienta (Carmina or Blow Up, 2012), both self-produced and self-distributed and exhibited on multiple alternative platforms – never made it to the LFF, let alone the UK film market. Still, the titles assembled by the festival’s Spanish-language cinema programmer Maria Delgado are an exemplary indication of the shifting state of affairs.

Jordi Cadena’s The Fear (La por, pictured above), a follow-up to his LFF-screened Elisa K, again deals with the day-to-day horrors of living with an abusive male family member. Cadena shared the festival’s Dare section with the always stimulating maverick Albert Serra, whose The Story of My Death (História de la meva mort) entwines the lives of Dracula and Casanova. Alberto Morais also reappears with The Kids from the Port (Los chicos del puerto), following his Spanish Civil War-related The Waves (Las Olas), shown at the LFF last year.

This year, though, I take my hat off to a bunch of great films by LFF first-timers: The Plague (La Plaga); The Wishful Thinkers (Los ilusos); and Wounded (La Herida) by Fernando Franco (better known as the editor of the mould-breaking Blancanieves): the latter was awarded the Special Prize and Best Actress Prize at the San Sebastián Film Festival in September. Unsurprisingly, all three films deal with some kind of ‘crisis’, personal, social or economic, but in their own idiosyncratic ways.

Wounded (La Herida)

Franco’s outstanding Wounded, which was selected for the festival’s First Feature Competition, is the film that tackles the idea of personal crisis most directly. In Spanish, the title, La herida – the singular feminine form of the word – refers to the film’s protagonist, self-deprecating Ana, a 30-year-old ambulance attendant in Madrid who suffers from a severe personality disorder that distorts her vision of the world, determining her hugely problematic relations with those close to her. The title can also be translated as the more neutral ‘the wound’, indicating the inability of those around Ana to deal with her mental illness.

A project first conceived as a documentary on people suffering this type of disorder soon morphed into a fiction, which, although not based on anyone in particular, has created a protagonist who rings excruciatingly true, not least thanks to Marián Álvarez’s jaw-dropping performance, the way she seems to inhabit the character completely. Although the film deals with emotionally charged and potentially manipulative material, the lack of backstory for Ana, together with Álvarez’s perfectly measured execution of her roller-coaster mood-swings, help transcend bleakness to fashion an immensely rewarding viewing experience.

You may take a few minutes to adjust to the overwhelming sepia look that engulfs docufiction The Plague. But once you have, this collage of interrelated personal stories located on the periphery of Barcelona manages to convey the mix of hope and struggle that Mexican Alejandro González Iñárritu aimed for with his grandiose and solemn Biutiful.

The Plague (La Plaga)

Writer-director Neus Ballús uses non-professional actors who play versions of themselves (a farmer, a Moldavian wrestler, an octogenarian woman, a Filipino geriatric nurse, and a prostitute). She soon turns the suffocating sepia into a visual metaphor for the heat – and in turn, the crisis – that is so cruelly lashing the country, as she tracks her protagonists on their daily efforts to survive. Prior to filming, Ballús spent a total of four years researching these characters’ lives.

Regardless of the grim subject matter of both films, there is always a hint of optimism, a will to look forward and move on, which in general permeates the films of this group of filmmakers. This is nowhere more true than in Jonás Trueba’s second film The Wishful Thinkers. Lighter in tone – as its title clearly suggests – than either Wounded or The Plague, it deals more explicitly with the effects of the economic crisis on all aspects of cinema and by extension the city of Madrid. It does so through the eyes of a young filmmaker, León, who finds himself unable to make a film.

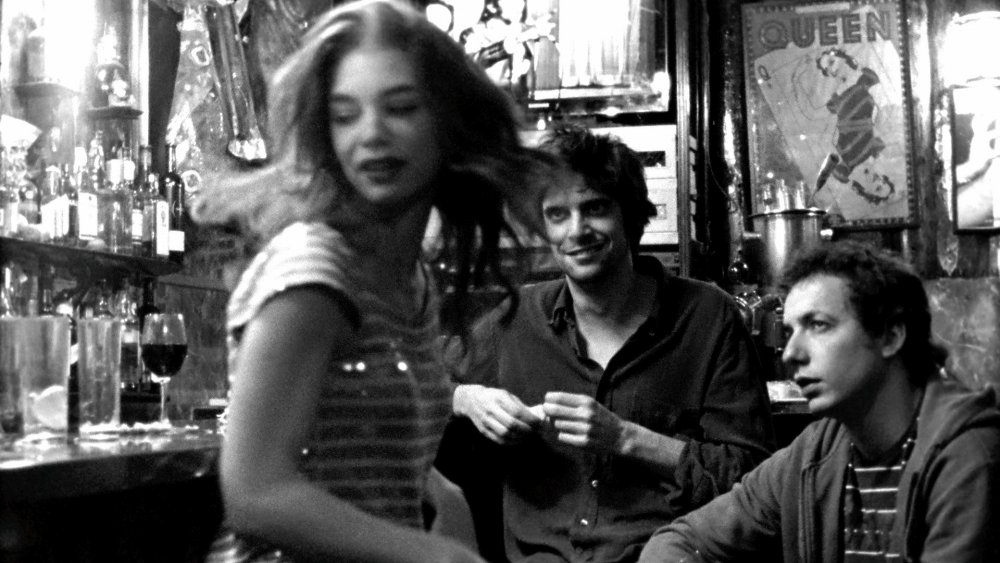

Laid-back, broke and impossibly romantic, Francesco Carril’s León does have an idea for a film, even if it’s not a very original one, but lacks the means to realise it. In the meantime he teaches cinema and meets a mysterious young woman with whom he roams the streets of Madrid. They drink in the magic of its cafés and bars in the small hours, and visit – perhaps for the last time – the city’s once numerous, now almost extinct rep cinemas and specialised bookstores.

The Wishful Thinkers (Los ilusos)

Filmed on discarded black-and-white stock, The Wishful Thinkers is not only a homage to a way of making cinema that seems to be rapidly disappearing, but also a warm, beautiful love letter to the Spanish capital – Almodóvar notwithstanding, surprisingly seldom a film’s protagonist.

Trueba’s film also includes a tongue-in-cheek cameo by the director Javier Rebollo, portrayed in a dream sequence as an almost mythical creature, briefly appearing then disappearing round the corner of one of Madrid’s many winding streets. When the dreamer finally catches up with Rebollo, he’s leaving for, significantly, Latin America to make his latest film (presumably last year’s LFF-screened The Dead Man and Being Happy). Everything here indicates that this is the continent that will soon have to become the source of many Spanish co-productions.

Jonás Trueba’s film shares a fair bit with his father Fernando Trueba’s debut, Opera Prima (1980), but with one huge difference. Where Trueba senior reflected the relaxed, unashamedly buoyant attitude of the early 80s (the transition from the all-pervasive control and censorship of Franco’s dictatorship to a vibrant democracy) in the capital, Trueba junior’s film is coloured by the city’s painfully slow decay. The mood is further darkened by León’s citation of the writer Chusé Izuel, who killed himself at the age of 24.

In spite of the undoubted difficulties, none of these characters give up. Ana, Léon and the protagonists of The Plague simply carry on fighting in an attempt to exorcise their demons, quietly adjusting to their changing circumstances. This capacity to take what comes, no matter what, gives them their best chance of survival – not unlike Spanish cinema itself.

The closing scene of The Wishful Thinkers neatly encapsulates this attitude: two little girls, completely unaware of the quasi-mythical status of film stock in this day and age, are filmed as they make new use of it, playing, pulling, cutting and jumping on it. So – at the risk of sounding as idealistic as Jonás’s ‘thinkers’ – these various filmmakers’ shared stance suggests a section they could have all to themselves, one called, not ‘Hope’ or ‘Wishful Thinking’, but rather ‘Transformation’ or ‘Rebirth’.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.