Breaking Bad took a long time to break big in the UK. The first season aired on the US cable channel AMC in January 2008, before being broadcast in the UK later that year on Sky’s FX channel. UK freeview channel 5USA showed season 2 in 2011, but never picked up subsequent seasons, which only gradually trickled out on DVD over here (season 3 took two years to reach these shores after its US transmission in 2010).

Breaking Bad is to stream on Netflix and to buy on Blu-ray, DVD and from digital stores.

As word of mouth spread, Breaking Bad started to gain a reputation as a ‘writer’s show’, namechecked in TV pitch meetings. But it was only with the UK launch of Netflix in 2012 that it really found a substantial British audience. By now there were four-and-a-half seasons available, and if you were really focused you could watch all 54 of the episodes so far during your month’s free Netflix trial. Earlier this year Breaking Bad achieved a unique twin peak of critical and popular recognition: an adulatory essay in the London Review of Books and a pastiche on The Simpsons. With the final eight episodes due to be broadcast in the US from 11 August, addicts are counting down the days.

So what is it about Breaking Bad that has proved so potent? When James Gandolfini died in June 2013, Bryan Cranston – who plays BB’s protagonist Walter White – tweeted: “I owe him. Quite simply, without Tony Soprano there is no Walter White.” Both shows focus on a middle-aged man balancing family issues and midlife crisis with the running of a major criminal enterprise. Both juxtapose violent acts with everyday domestic concerns, to variously comic or shocking effect. The difference is that whereas The Sopranos showed us the ordinariness at the heart of an evil man, BB shows us something potentially far more challenging: the evil at the heart of an ordinary man.

At the start of episode 1, Walter White is not yet a criminal: he’s a down-trodden high-school chemistry teacher who has just turned 50 and is about to discover he has cancer. If that isn’t enough to make us feel sorry for him, his teenage son has cerebral palsy, his wife is pregnant with an unplanned baby, he’s patronised by his asshole cop brother-in-law and – we will learn – while he once had a stake in a technology start-up, he sold out years ago for $5,000; his former partner is now a billionaire, while Walt has to do a second job at a car-wash to make ends meet.

It might seem that writer/creator Vince Gilligan is stacking the sympathy odds in Walt’s favour. But it’s necessary, because over the ensuing 53 episodes (and, no doubt, the eight still to come), we follow this decent, intelligent family man’s utter – and entirely self-willed – corruption, one tiny, incremental step at a time, as his initial dabblings in cooking crystal meth eventually put him at the centre of a murderous drugs empire. Little by little, Mr White goes dark, until – in Macbeth’s words – he is “in blood/Stepp’d in so far, that, should I wade no more,/Returning were as tedious as go o’er.”

It’s not idle to quote Macbeth, because BB is indeed a tragedy of Shakespearean proportions, spread out not over five acts but over 62 (or arguably, since each episode could be said to have three acts, over 186). The definition of tragedy in Christopher Booker’s 2004 compendium of story structure, The Seven Basic Plots, could have been written with BB in mind:

“A hero [is] tempted or impelled into a course of action which is in some way dark or forbidden. For a time… the hero… enjoys almost unbelievable, dreamlike success. But somehow it is in the nature of the course he is pursuing that he cannot achieve satisfaction. His mood is increasingly chequered by a sense of frustration. As he still pursues his dream, vainly trying to make his position secure, he begins to feel more and more threatened – things have got out of control. The original dream has soured into a nightmare where everything is going more and more wrong. This eventually culminates in the hero’s violent destruction.”

Well, on that last point, the jury is still out. We will have to wait until the final episode airs in the US on 29 September.

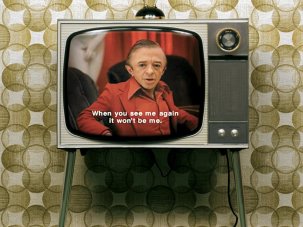

BB’s status as a 186-act tragedy is, however, something that Sony Pictures Television has been at some pains to conceal – and the mixed message of its marketing is perhaps one reason for the show’s slow uptake over here. The DVD packaging, for instance, initially cried comedy. The Complete First Season shows the climactic image from episode 1: Walt, in glasses, green shirt and Y-fronts, standing in the desert with a gun in his hand, as smoke gushes from his RV. The show does undoubtedly have its grimly comic moments, thanks not least to Walt’s exasperated mentorship of his former-student-turned-partner-in-crime Jesse Pinkman (Aaron Paul). But then so does Macbeth.

In the wake of BB and its back-to-back Primetime Emmy awards for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Drama Series (2008, 2009, 2010) Bryan Cranston has recently emerged as a character actor in prestigious Hollywood thrillers (Drive, Argo). But before BB, he was best known for playing the hapless father in the long-running family sitcom Malcolm in the Middle (2000-06). Seinfeld fans may also (just) recognise Cranston from his occasional role as Tim Whatley, a smooth Wasp dentist who riles Jerry by converting to Judaism.

So BB doesn’t just succeed in discovering the murderous self-interest at the heart of suburban man; it discovers it in the shape of a man with the initial menace factor of, say, an American Richard Briers. (Though the enigma at the heart of Cranston is hinted at momentarily in Seinfeld, when Jerry wonders apropos Tim’s alleged sexual peccadilloes: “Is this guy a dentist or Caligula?”)

In one way, however, BB is the dark underside of a show like Malcolm in the Middle. As demonstrated by the 2011 documentary series America in Primetime (recently screened on the BBC as The United States of Television), BB – like The Sopranos – fits into a venerable tradition of US TV shows focusing on an everyman father struggling to hold it all together. This is largely a comic tradition, going back to shows such as Father Knows Best (1954-60) and The Dick Van Dyke Show (1961-66), and in BB there is undoubtedly an element of recognition and wish-fulfilment for care-worn dads as they watch the worm turn.

In episode 1, Walt – with nothing to lose now he has been diagnosed with cancer – stands up to the bullies who have been mocking his son’s slurred speech in a clothes shop. We root for him as he gets one over on the system by settling the medical bills his insurance refuses to cover with the proceeds of his increasingly lucrative drugs business.

But all this is cleverly sucking us into identifying with Walt until the point somewhere between seasons 1 and 5 (and it will come in different places for different viewers, providing a kind of morality litmus test) when we realise that his actions are no longer enterprising, chemistry-teacher-like solutions to cash-flow problems but in fact heinous crimes in which he takes not just pride but a kind of fascistic glee. As Walt himself puts it to his wife Skyler (Anna Gunn) in a much-YouTubed speech in season 4, episode 6: “I am not in danger, Skyler. I am the danger.”

The thinking-ahead protagonist

Episode 2 of season 1 of Breaking Bad is entitled Cat’s in the Bag…, followed immediately by episode 3, …And the Bag’s in the River. Connoisseurs of film noir will spot this as a quotation from Alexander Mackendrick’s 1957 classic Sweet Smell of Success (I told you this was a writer’s show). Of course, in terms of its influence on current American TV, Sweet Smell of Success really belongs in an article about Mad Men. But there is also a useful connection to be made in terms of BB.

Part of the satisfaction of Mackendrick’s film lies in seeing clever, devious people who are always thinking one step ahead. This was an article of faith for the director who, in his invaluable tome On Film-making, memorably wrote: “A character who is dramatically interesting is intelligent enough to think ahead. He or she has not only thought out present intentions, but has foreseen reactions and possible obstacles. Intelligent characters anticipate and have counter-moves prepared.”

Once again, these words could almost have been written with BB in mind. As well as being a tragic hero, a sitcom-style beleaguered dad and a figure of midlife-crisis wish-fulfilment, Walt is also very much in the British tradition of the crafty middle-class murderer. Like Dr Crippen, he is skilled in what he calls “chemical disincorporation”, using acid to dissolve bodies in the bath. (Unlike Jesse, Walt also knows that the bath needs to be made of plastic, otherwise it will dissolve too, with very messy results: see Cat’s in the Bag.)

The ability to plan ahead is in fact Walt’s defining characteristic. In this respect, …And the Bag’s in the River is a key episode (and, for viewers coming to the series for the first time, the one where they will know for sure whether this show is for them).

The episode revolves around Walt’s decision about whether to kill a Latino drug dealer (who has previously tried to kill him). At one point, as he agonises, Walt writes a list to weigh up his options. One column reads, “Let him live”; the other, “Kill him”. Under “Let him live” he lists: “It’s the moral thing to do”; “Judeo/Christian principles”; “You are not a murderer”; “He may listen to reason”; “Post-traumatic stress”; “Won’t be able to live with yourself”; “Murder is wrong”.

In the second column there’s just one entry: “He’ll kill your entire family if you let him go.” It’s utterly deadpan, utterly black – but also a peerless insight into Walt’s character and thought processes.

Breaking Bad (2008-13)

In its focus on an everyman sucked into a world of violence and treachery, BB undoubtedly qualifies as noir. Though it has employed the services of many different writers and directors (among the latter a few recognisable noir journeymen such as John Dahl, Rian Johnson and Tim Hunter), the show is above all the work of creator and showrunner Vince Gilligan, writer of over a dozen key episodes, from the pilot to the forthcoming series finale, and director of half-a-dozen. There’s little in Gilligan’s previous filmography to hint at his mastery of noir. Initially working in movies, he had writing credits on the 1990s comedies Wilder Napalm (1993) and Home Fries (1998), and more recently on the Will Smith superhero vehicle Hancock (2008). In television, he cut his teeth on 30 episodes of The X Files (1993-2002) and possibly learned a trick or two from Michael Mann on the barely seen Heat spinoff Robbery Homicide Division (2002).

Of course The X Files added a dash of noir to its sci-fi, not least its shadowy cinematography. By contrast BB – which has noir themes at its black heart – wholeheartedly embraces the dazzling desert light of its Albuquerque, New Mexico setting, so that these darkest of deeds unfold in an incongruously bright and colourful palette. It’s a palette over which a great deal of care has been taken: the pilot was shot by John Toll, who shot The Thin Red Line for Terrence Malick; my wife has a theory about the colour-coding of the costume and production design that I won’t even begin to try and summarise here.

BB may be a writer’s show, but for television it’s also highly visual, to the extent that Albuquerque itself functions as a metaphor for Walt’s psyche: a thin crust of suburban bungalow civilisation on top of a desert. It’s no accident that Walt and Jesse – in search of a safe place to ‘cook’ – turn Jesse’s RV into a mobile meth lab and drive it out into the desert. It’s as if Walt is deliberately leaving his conscious, civilised self behind to go on an excursion to his uncharted unconscious and embrace what Jung would call his ‘shadow’ and George Lucas his ‘dark side’. Except in the skewed world of BB, the dark side is very, very bright indeed.

The New Mexico desert setting also helps qualify BB as a western. Much is made of the black hat worn by Mr White after he loses his hair to chemotherapy. The fundamental theme of the western – that by doing ‘what a man’s gotta do’ to make society safe, you in the process make yourself unfit to live in that society – is reflected in microcosm in Walt’s family, as his heroic efforts to provide for his loved ones after his death lead to the breakdown of his marriage.

The stand-out episode in the first half of season 5, Dead Freight, even revolves around an elaborate train heist that’s as gripping and spectacular as any the big-screen Wild West had to offer. But crucially – and typically for BB – it’s more than just a set piece. The thrills and spectacle are just softening us up for another turn of the screw: the heist’s completely unexpected aftermath, perhaps the most shocking of all the crimes in which Walter White has been complicit. So far…

-

The 100 Greatest Films of All Time 2012

In our biggest ever film critics’ poll, the list of best movies ever made has a new top film, ending the 50-year reign of Citizen Kane.

Wednesday 1 August 2012

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.