The last outing from Belgian director Joachim LaFosse was Our Children (2012), a psychologically acute, quietly riveting and unspeakably grim reconstruction of an appalling true-life tabloid case: the murder of four young children by their distressed mother (essayed with memorable fragility by Émilie Dequenne.)

His long-awaited follow-up, The White Knights (Les Chevaliers blancs), is more narratively propulsive but no less challenging. It is also based, albeit “loosely”, as an opening title card puts it, on a real-life children-in-peril situation, in which a French charity organisation posed as an NGO under the moniker ‘Zoe’s Ark’ in order to spring 103 children from civil war-ravaged Chad and transport them to French families, with whom they were in constant phone contact. At no point did they reveal their true identities or intentions to the villagers or the children, believing that their ends justified their indisputably dubious means.

Before watching the film, I was intrigued by its title, and convinced that it couldn’t possibly be as unambiguously positive as it riskily implied – after all, Our Children was distinguished by its rigorous interrogation of the complexity of the postcolonial experience in Belgium. My suspicions about the title’s bleakly ironic properties were confirmed immediately. LaFosse plunges the viewer, with blessedly minimal exposition, into a chaotic situation where grey is the dominant shade (and not in a kinky way): these ‘White Knights’ — here renamed “Move For Kids” — seem to be doing their best, but they constantly bicker and challenge each others’ senses of ethical rectitude.

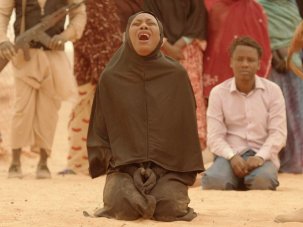

The White Knights (Les Chevaliers blanc, 2015)

The opening moments, filmed by LaFosse with a scuffling, handheld urgency – a style he maintains throughout to mesmerising effect – follow leader Jacques (Vincent Lindon) as he tries to strike a deal with a fixer, played with electric shiftiness by A Prophet’s Reda Kateb, for an transport aircraft. It’s difficult to keep up with the detail of what’s actually happening, and this situation never really changes for the viewer. At each step of the breakneck narrative, LaFosse deliberately imparts key information to the characters at the same time as the viewer: it’s a direct challenge to remain engaged, and one I was thrilled to accept.

Crucially, however, Lafosse does let the viewer know more than the villagers, which engenders an uncomfortably implicative quality. We’re forced to make our own judgements on the efficacy of the group’s myriad fibs as soon as they are told. Meanwhile an intriguing, skilfully integrated subplot about the ethical role of a documentary filmmaker within the crew layers proceedings with a further moral altostratus.

LaFosse’s film is technically bracing, and it’s also powerfully acted. Lindon, as leathery, gruff and fumigant as a human cigar, is the standout: he marches around conveying the impression that if he were to cease his mission for one moment – or, more disturbingly, if he were to reflect seriously on the ambiguity of his actions – he would spontaneously combust. The performance of newcomer Rougalta Bintou Saleh, as the group’s indispensable interpreter, is also mesmerising for its watchful stillness.

The White Knights (Les Chevaliers blanc, 2015)

The White Knights, then, is no simple tale of heroism, although one can sadly conceive a bowdlerised Hollywood version going the whole hog on the time-honoured ‘white saviour’ narrative. But neither is it a straightforward takedown of destructive liberal do-goodery (for that, I’d recommend Raoul Peck’s bafflingly underseen documentary Fatal Assistance, a furious appraisal of the shambles left by aid organisations in post-earthquake Haiti.) LaFosse is a compassionate filmmaker who believes in the innate goodness of humanity even as its flaws become disturbingly apparent. There’s no sense of him hectoring the viewer, or exerting judgement of his own. His skilled deployment of a muscular, boots-on-the-ground thriller framework for such tricky material allows the the tension to build remorselessly while the brain remains engaged and stimulated. I was stunned, brought up short by its abrupt ending, and left to reflect on its portrayal of the limits of liberalism in action.

-

Toronto International Film Festival 2015 – all our coverage

Follow our reviews from the 40th edition of TIFF.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.