Spoiler alert: this review reveals a plot twist

As the world becomes increasingly saturated with visual media – with screens in our pockets, in restaurants, in elevators, taxicabs, vending machines and all sorts of places where they didn’t used to be – our collective visual literacy doesn’t seem to be keeping up. This is probably because arts programmes are the first to be cut in publicly funded schools, and when they do exist, it’s on a specialised track. It’s also undeniable that international art-speak (the semi-academic, self-important, totally incoherent language of gallery press releases and artists’ statements) and the perceived frivolity of mid-century conceptual art (ie the ‘my kid could do that’ refrain) have undermined art’s place in the public’s interest.

Sweden/France/Germany/Denmark/USA/Norway 2017

Certificate 15; 151m 26s

Director Ruben Östlund

Cast

Anne Elisabeth Moss

Julian Dominic West

Oleg Terry Notary

Christian Nielsen Claes Bang

Michael Christopher Laessø

[1.85:1]

UK release date 16 March 2018

Distributor Curzon Artificial Eye

curzonartificialeye.com/the-square

► Trailer

Yet the cloistered, fundamental silliness of the contemporary art world is not Ruben Östlund’s target in The Square – that would be too easy. As with his previous films Play (2011) and Force Majeure (2014), Ostlund uses his setting to explore hidden inequalities in supposedly liberal societies, particularly those concerning masculinity, race and class, playing with our expectations about what is supposed to happen versus the results, which are always uncomfortable.

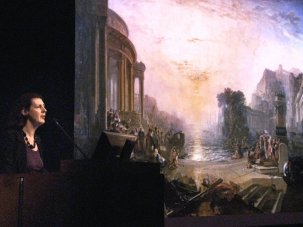

The Square is set in a Sweden where the monarchy has been abolished; the royal palace in Stockholm is now a non-profit gallery of contemporary art, aptly titled the X-Royal Museum. Christian Nielsen (played by the unequivocally handsome Dane Claes Bang) is head curator, competing with art collectors to get the latest and greatest works that question our relationship to space and the notion of being a good person. (Arrows pointing to and from the eponymous installation are labelled “I trust people” and “I don’t trust people.”)

However, Christian’s life is, like our own, grey to black: after having his mobile and wallet stolen (in a choreographed grift that could itself be performance art), he tracks the thief to a rundown apartment block and attempts to retrieve his property by distributing threatening letters to every flat. He quickly gets back the stolen items, but also begins to receive more things (cufflinks, other mobiles) and even an enemy: a small Arab boy whose parents have punished him severely because, thanks to Christian’s actions, they believe he’s a thief.

The fallout from this retrieval operation causes Christian to neglect his duties at work, which is why a wildly offensive YouTube video to promote The Square gets his approval. (In it, a blonde homeless girl holding a pitiful-looking kitten is blown up inside The Square). During the pitch meeting, the hip marketing guys start by stating, “Your competition isn’t other museums but natural disasters, terrorism and controversial moves by far-right politicians.” While this is undoubtedly true – the internet flattens outrage into a single continuum without any sense of the scale of importance of these very different events – Östlund doesn’t dwell on the point. Instead, like the internet itself, he simply moves along.

Elijandro Edouard as the Boy with Letter

Throughout the film there are many small gags and standalone vignettes – half-Tati, half-Vine – that take a stab at the contradictory, unequal nature of western liberalism. Östlund never explicitly says that the museum’s staff is diverse in name only, but rather shows how the one female assistant and one black assistant are stuck doing low-grade tasks (directing guests to exhibits, sorting out Christian’s mobile) and are ignored during the YouTube presentation. Likewise, The Square never spells out the facile nature of the X-Royal’s mission, but makes it perfectly clear through silent shots of the art (a giant pile of schoolroom chairs, for example), the disinterested visitors and Christian briefly admiring the work of a pet chimp.

Glimpses of life outside the museum frequently show people begging for change, nudging at the question of the prestige of helping art versus the often thankless task of helping the poor. The only beggar Christian decides to help insists he buy her a sandwich without onions, but he finds this request rude and so fails to comply. The mechanics of Christian’s personal and professional downfall are completely tied up in this inability to interact with the world in a way he doesn’t perceive as polite or self-protecting – he only bothers to do what he thinks is right for him, not what might be right for the other person. This plays out in his casual relationship with Anne, an American journalist (Elisabeth Moss). He is a man continually undone by the awareness of his privilege, and while the ending provides some sense of hope, it’s tenuous.

In the April 2018 issue of Sight & Sound

Playing to the gallery

Swedish director Ruben Ostlund’s latest spectacle of social embarrassment and abjection, The Square, takes aim at the pretensions of the art world, in its mischievous portrayal of a suave Stockholm gallery director who singularly fails to live up to his own high ideals. By Jonathan Romney.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.