Cases of sexual assault and harassment are never really about sex, they’re about power. That’s a fact encapsulated in the memorable way former Weinstein Company junior executive Lauren O’Connor describes the relationship between herself and the man whose abusive behaviour she witnessed at work: “Harvey Weinstein is a 64-year-old, world-famous man and this is his company. The balance of power is me: 0, Harvey Weinstein: 10.”

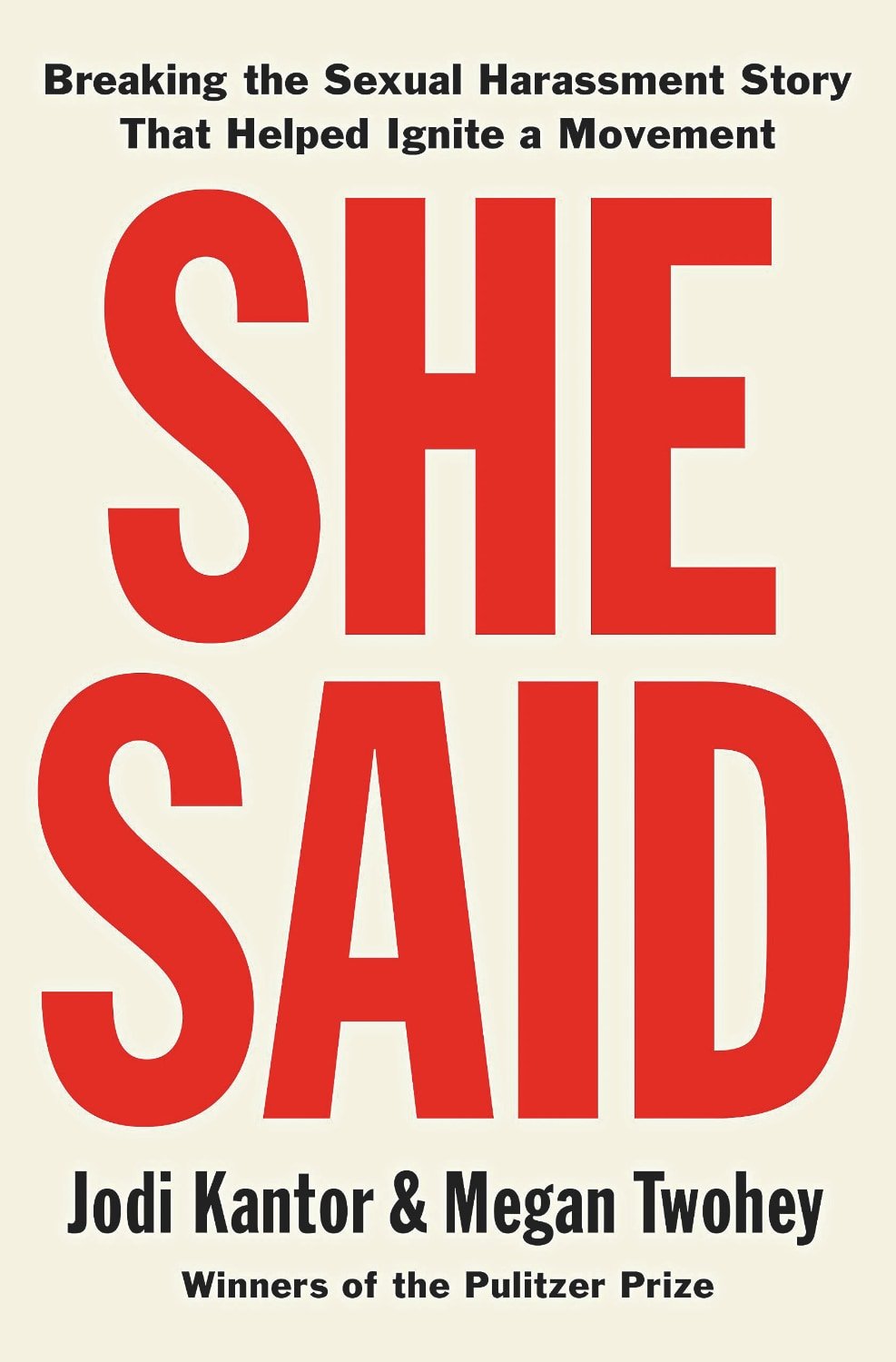

She Said: Breaking the Sexual Harassment Story that Helped Ignite a Movement

By Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey (Bloomsbury Circus)

As this important book slowly uncovers, what goes for junior executives goes for women at all levels of the industry, even Hollywood stars. The system that remains at the heart of the film industry is stacked in favour of the producers, and increasingly it seems that every salacious titbit one has ever heard about producers and starlets is an elaborate cover story for a massive abuse of power.

Power is also at the heart of the reporting of such allegations, as this engrossing memoir by Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey, the New York Times journalists who broke the story about Weinstein in October 2017, makes abundantly clear. She Said is not just about confronting power, in the form of the strong-arm tactics that Hollywood producers with a team of lawyers can afford to employ when reporters get too close to the episodes they want to keep secret. Nor the strength of nondisclosure agreements, threats and promises that keep present and former employees quiet.

It’s also, for journalists, about deploying one’s own heft with discretion. At several points in this tale, Kantor and Twohey could have rushed to print with a story that would have made waves, and boosted the traffic and circulation of the New York Times, but that could have been swept away by a lawyer’s denials, and destroyed the lives of the women who had entrusted them with their testimony. This book is not just about an insidious history of harassment, but also about when to hold back and when to publish – when enough women feel safe to come forward, when there is enough hard evidence on file, and when the accused has been given a chance to respond.

As such, it’s a story filled with enough strategy and suspense to make a satisfying film thriller, despite the sickening subject matter. And it moves fast. In the spring of 2017, the case against Weinstein was nothing but rumours, rueful Hollywood in-jokes about not accepting an invite to his hotel suite and a police investigation into an accusation of groping that failed to result in a criminal charge. But the actor Rose McGowan had recently posted on social media about being raped by an unnamed producer, saying: “It’s been an open secret in Hollywood/Media & they shamed me while adulating my rapist,” and Kantor, who was working in the investigations department at the New York Times, heard whispers that Weinstein was the assailant. Getting McGowan to talk to reporters wasn’t easy, but when she finally did, the story she told was horrific.

As Kantor and Twohey chased more leads, and spoke to more and more women, the pattern seemed to repeat: somebody knew that a woman had a story, a complaint against Weinstein, but for wholly understandable reasons she was wary of speaking to a journalist about it. When they did eventually share their experiences, the similarities between each sad and sordid tale were uncanny, with each new account reinforcing the last: “The sickening repetition of the hotel room stories. The apparent targeting of women who were new on the job. The terrible bargain of sex for work, and the longstanding silence of those who knew.”

While many readers will feel very familiar with the details of the charges against Weinstein by now, this book gives a fresh perspective on the case, and in particular a more considered take on the decision of each woman involved to speak up or not. These decisions are gruelling, and very personal, and because She Said is a much more intimate story than the press reports, it offers an insight into that wrenching process.

By the summer of 2017, Kantor and Twohey had heard enough to more than convince them that Weinstein was a serial abuser, but not enough to print. Ultimately it took a senior male executive from the Weinstein Company to break his silence, in order for the women to be heard. Irwin Reiter, former vice-president of accounting and financial reporting, had an idea of what was happening because he saw the amount of money going out to various women, and eventually he agreed to talk to Kantor, and to share Lauren O’Connor’s eloquent memo.

And it ends, like all stories about power, with the fact that whenever we doubt victims, we believe the money. The headline the New York Times ran with in October 2017 was: “Harvey Weinstein paid off sexual harassment accusers for decades.” The payoffs, intended to silence women, became proof of the veracity of their statements.

The subtitle of this book asserts a claim bolder than a mere journalistic scoop: Breaking the Sexual Harassment Story That Helped Ignite a Movement. The authors place their 2017 investigations in a broader context, including crucial precursors such as Anita Hill, the lawyer who accused US Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas of sexual harassment in 1991, and Tarana Burke, the activist who actually started the #MeToo movement, as well as more recent history too.

Before they began digging into Weinstein’s past, the new US president had been caught on tape appearing to celebrate such abuses of power, bragging about sexual assault. His attitudes to women and repeated claims of ‘fake news’ created a uniquely hostile environment for Kantor and Twohey’s work, and surely contributed to many of Weinstein’s alleged victims staying silent. Gallingly, Weinstein had been present at the women’s march the day after Donald Trump’s inauguration, surrounded by women wearing pink ‘pussy hats’ in protest at the idea that powerful men had a right to their bodies.

And then, after the New York Times story was published, Kantor and Twohey became involved in supporting Christine Blasey Ford’s brave attempt to bring US Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh to account for an alleged rape. Depressingly, the failure of that challenge to his appointment brings our story full circle back to Hill.

Weinstein is currently wearing an ankle monitor and awaiting trial, while Kantor and Twohey, along with Ronan Farrow from the New Yorker, have been awarded the Pulitzer Prize for their work in bringing the accusations against him to light. (Farrow’s own book about his investigation into Weinstein, Catch and Kill: Lies, Spies, and a Conspiracy to Protect Predators, has also just been published.) While we celebrate their journalistic rigour and support of vulnerable women, this book is a reminder that the movement is only just beginning, and the battle for equality is far from over.

-

Women on Film – all our coverage

A window on our ongoing coverage of women’s cinema, from movies by or about women to reports and comment on the underrepresentation of women...