Web exclusive

Tim Roth on stage at the 2015 Morelia International Film Fesival

Credit: moreliafilmfest.com

Long-time readers may recognise Morelia as a place I’ve written about in the past – in 2005, for what was only its third edition, and again in 2012, by which time it had established itself as Mexico’s must-do festival. In those reports I focussed on two areas: low-budget Mexican documentaries that deal with the problems of indigenous peoples or potential economic migrants, and the relevant year’s crop of new Mexican feature films.

13th Festival Internacional de Cine de Morelia

23 October-1 November 2015 | Mexico

These strands still form the core of Morelia’s programme, yet on this visit I did not pursue them – even though my impression from talking to others was that it was a good year for such films. Instead I took a different tack, partly because I was dropping in on the festival during a holiday, and partly to give a better flavour of how multifarious this festival can be and to explore the reach of its cultural ambitions.

Among the most distinctive and special things about Morelia is its curation of guests – not a subject we usually write about in S&S and a difficult thing to convey without seeming either gossipy or starstruck. Considering the festival is set in a relatively obscure town in Michoacan province, the pull Morelia has with talent is quite amazing.

I arrived on the day that Tim Roth was to be honoured. He had come not only to promote his excellent, hyper-controlled, often-silent performance as a male nurse in Michel Franco’s Chronic, but also to present his one stab (so far) at direction, the emotionally harrowing child abuse tale The War Zone (1999).

Roth was presented to the crowd by Cannes’s boss Thierry Fremaux (in fluent Spanish – apparently he spent part of his childhood in Argentina). The Cannes connection is central to the existence of Chronic, which premiered In Competition this year. Roth had met Franco while presiding over the Un Certain Regard jury that had given Franco’s After Lucia its prize in 2012. The actor is also strongly connected to Quentin Tarantino, who’s another fan of Morelia, and features in Tarantino’s imminent film The Hateful Eight. So when Roth – while happily mugging away for photographers in the new cinema seat that bears his name – said he wanted to come back to Morelia with a programme of films by Alan Clarke (the late UK director who gave him his first break in Made in Britain), one knew he was sincere.

Momentarily I ran into another Brit, Peter Greenaway. The steely hair and pinstripe suit immaculately in place, he sat down to a snatched lunch having rushed there from a screening of his [as he might say] provocatory, biographemous new film Eisenstein in Guanajuato (which I wrote about from Berlin in S&S April 2015). With his taxi to the airport imminent, he was polite, mostly reserved and then gone. I’d just flown in with my friend, the producer and educator Lynda Miles, who was on the jury, and producer Kate Ogborn (my wife), who was presenting Abandoned Goods, Pia Borg and Edward Lawrenson’s prize-winning documentary about outsider art. We knew that Stephen Frears was soon to arrive to promote his Lance Armstrong biopic The Program. All these compatriots were in Morelia to help mark 2015 as the year of the British Council’s cultural promotion project ‘The UK in Mexico’.

Yet at the lunch buffet, the French presence seemed at least as substantial: Fremaux, the documentarian Nicolas Philibert, Palme d’Or winner Laurent Cantet, programmer and talent-hunter Pierre Rissient, Cannes Critics’ Week programmer Charles Tesson, former programmer Jean-Christophe Berjon and critic Jean-Michel Frodon.

Amnesia (2015)

On my second day there, Fremaux introduced Barbet Schroeder’s latest film Amnesia, set in Ibiza, where Schroeder has a home, and based on experiences his German mother had as a long-term resident of the island. Later in the festival, Schroeder’s iconic hippies-turn-junkies-in-Ibiza film More (1969), with its famous Pink Floyd score, was shown, the two titles acting like bookends of a long and distinguished career (not that it’s over yet). Schroeder proved a winning presence throughout the festival, though I confess I found Amnesia a little clumsy (Schroeder explained that it was shot in just two weeks).

Amnesia is set in the early 1990s. A handsome elderly woman, Martha – the character based on Schroeder’s mother and played by Marthe Keller, of Marathon Man fame – has been living happily alone on Ibiza for 40 years. Her new neighbour, Jo (Max Riemelt), is a twentysomething wannabe DJ keen to make his mark on Ibiza’s burgeoning techno scene. The two become unlikely platonic soulmates, bonding over food and music, and during their phases of hanging out together, Jo learns that Martha refuses to ride in a Volkswagen or drink German wine for political-historical reasons that remain obscure until Jo introduces her to his own German family, and the bitter legacy of World War II returns to bite them all back. It’s a slow-burn musing talkfest that charms at times but I found it hard to get into partly because, whenever the actors were being warmly emotional in English – and it’s important for the story that they do stick to English – they sound, to these English ears, unconvincing.

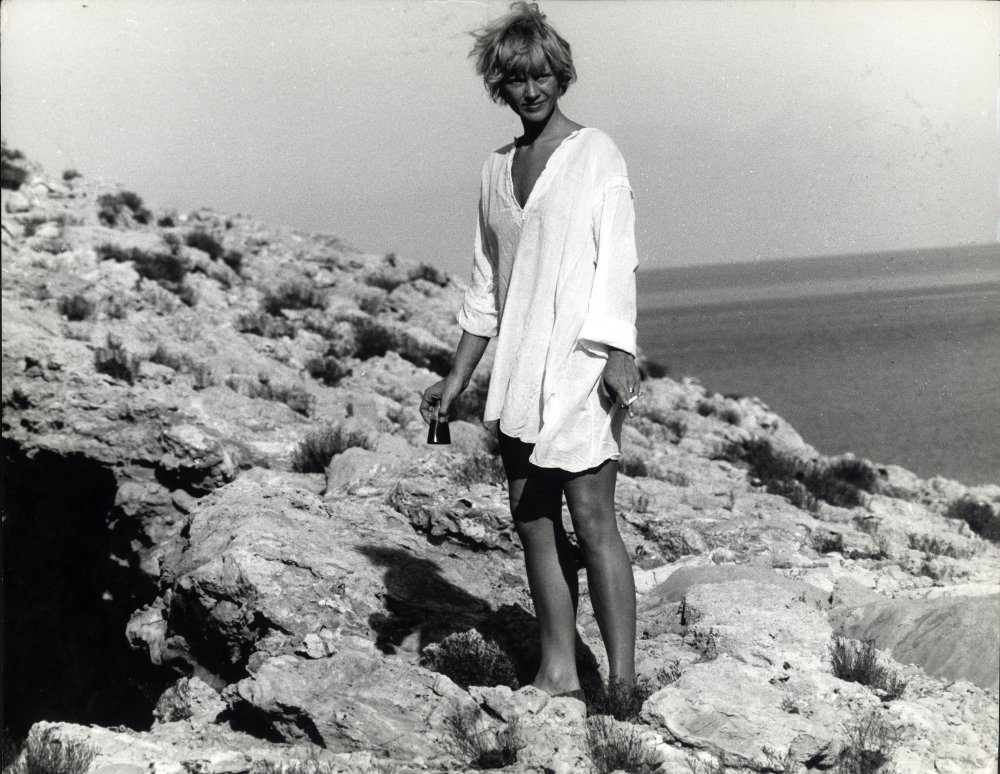

More (1969)

The same problem exists, albeit to a lesser extent, in More, in which Stefan (Klaus Grünberg), a young German student, seeks adventure in the footsteps of Estelle (Mimsy Farmer), an enigmatic American girl who leads him to Ibiza, where she’s entangled in some way with an ex-Nazi. The film plays out like many films about a couple who fall into heroin addiction – the rituals and paraphernalia are all given the usual reverence – but the quite breathtaking beauty of the soon-to-be-obscure 60s starlet Farmer (a female double for David Bowie) and the island itself count for much in the way of recompense.

Ibiza happens to be one of the settings of one of my favourite Phillip Garrel films, J’entends plus la guitare (1991), in which, with some echoes of More, he retells the story of his ten-year junkie relationship with Nico, the famous chanteuse of the Velvet Underground. Garrel’s latest film, In the Shadow of Women, is as characteristically centred on the shifting romantic allegiances of bohemian couples as most of his output, except that he now includes a more critical perspective on hypocritical male behaviour. Here a happily married documentary filmmaker succumbs to a Parisian ménage à trois, but then finds the tables turned on him. The film was represented in Morelia by actress Clotilde Courau, who is quite wonderful as the traduced wife.

In the Shadow of Women (L'Ombre des femmes, 2015)

I got talking to her after we’d both seen a panel discussion on the way documentary might be shading into fiction. Chaired by S&S’s very own Nick Roddick, this talk featured a chatty Wash Westmoreland (director of Still Alice), Cantet, Schroeder and Stephen Frears. Anyone who has ever seen Frears on stage will know that he is mischievous, easily bored and likes to make the life of journalists difficult. Roddick certainly had his work cut out as Frears more or less rejected the premise of the conversation, saying – of Cantet talking about his drama-doc The Class (2008) – “The way he talks about making films is exactly what I do. I don’t see the difference.”

What left Courau in mild shock, however, was Frears’s response to a question from me. Knowing his views, I asked him to explain his disavowal of auteurism. He talked about the way he enjoyed going to see films when he was a child, in blissful ignorance of how they were done, and then said, “Basically, it all started to go wrong with Breathless.” “Is this supposed to be funny?” Clotilde asked me. “The British sense of humour?” “Well, yes and no,” I said. “He really does mean it.”

Out of the blue, Morelia’s brilliant festival programmer Daniela Michel asked me to conduct a career interview onstage in English with Isabelle Huppert. The actress – for me the best screen actress currently working – had come to Morelia along with three films – Guilliame Nicloux’s wilderness trip Valley of Love, Samuel Benchetrit’s oddball comedy Asphalte and Joachim Trier’s overwrought melodrama Louder than Bombs – all of which had premiered at Cannes. I knew that Huppert might be formidable, yet I also knew – from people who know her – that she could be warm.

Her onstage performance was, from my perspective, pleasingly generous, serious and wide-ranging. She began by talking about Mikail Kalatozov’s The Cranes Are Flying (1957), which she said was the first film to have a major effect on her, then she moved through her whole career with sharp observations on working with Chabrol and the like (it was not all about the pleasant meals) or without a script (as she did for Hong Sangsoo) and even mentioned working on Michael Cimino’s epic Heaven’s Gate. I’m being sketchy here because we hope to publish the full interview in an upcoming issue.

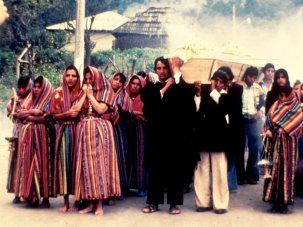

You can see from these examples that the stream of guests at Morelia is of a constantly high standard (and I’ve not included here the constant stream of Mexican talents). But scholars and enthusiasts, too, get a look in. Pierre Rissient’s presentation of Herbert Biberman’s The Salt of the Earth (1953) gave a fascinating exegesis of this film deliberately set up to give work to filmmakers suffering under the McCarthyite black list. Paired here with the Robert Mitchum-starring gunrunning saga The Wonderful Country under the rubric ‘Imaginary Mexico’, The Salt of the Earth is a stirring recreation of a strike by Mexican-American mineworkers to gain equal pay to their ‘white’ co-workers. The extraordinary ensemble cast mixed real miners with great US and Mexican actors such as, respectively, Will Geer and the wonderful Rosaura Revueltos, the latter giving voice to a strong feminist theme in the film when the women take over from the men on the picket line to save them from arrest.

The Salt of the Earth (1954)

Another potent rediscovery from the 1950s here was Torero (1956), a semi-fictionalised bio-documentary made to celebrate the life of Mexican bullfighter Luis Procuna. The serviceable monochrome print was given a surreal edge at the screening I attended by the reels being projected in the wrong order, which meant one had to piece together the chronology in one’s own mind, but given the astonishing documentary images collected here, which tended to focus on harm done to the bullfighter rather than the bull, it didn’t matter too much. We’re used to feeling revulsion at the torture of the animal but never before have I understood the dynamic between a crowd baying for the matador to get closer to the horns and the frequency with which they get gored. And when, in his later career, Procuna doesn’t get close enough, he’s treated to the vivid image of a rain of seat cushions thrown into the ring in utter contempt.

When I wasn’t guest-watching, I was enjoying the somewhat hokey pleasures of ‘Mexican Gothic Cinema: Between Horror and Delirium’. I began with Juan Bustillo Oro’s stark melodrama Two Monks (1934), in which a devil-haunted brother assaults his would-be exorcist, who then turns out to be his one-time romantic betrayer, and we see the same story in flashback of a simmering love triangle told twice, each from the other’s point-of-view. Oro brings a number of (for the time) avant garde techniques into play, including some quite stunning juxtapositions, and the rather wonderful trick of having the hero of each version wear white, the villain black, thereby reversing in the second part what we saw in the first.

Fernando de Fuentes’s The Phantom of the Convent (1934) sees three well-heeled ramblers seek shelter for the night in what they’ve been told is an abandoned convent, yet within they find an entire community of uncommunicative brethren, including one who is confined to his cell for an unpardonable crime. It’s big on a gloom-laden yet feverish atmosphere and very condemnatory of pre-marital sex.

The Skeleton of Mrs. Morales (El Esqueleto de la señora Morales, 1960)

My favourite of these treats was The Skeleton of Mrs. Morales (1960), which concerns a taxidermist whose manipulative, sex-censoring hyper-religious wife seems determined to wipe the blithe smile off his beaming, liquor-loving face until he’s had enough and begins to look at her as a future subject for his work. It all feels very Mexican, as long as you ignore the fact that it’s based on an Arthur Machen story, The Islington Mystery.

I saw my final gothic treat after the official festival was over, but amid the Day of the Dead celebrations in the town of Patzcuaro in the absolutely gorgeous restored cinema The Emperador Caltzontzin Theater. They showed Fernando Mendéz’s El Vampiro (1957) straight after we had met the local governor and his entourage (I was told that many of his predecessors are now in prison). The film tells pretty much the classic Dracula story, beginning with the arrival at a Sierra Negra train station of a mysterious box from Hungary, along with a potential victim and rescuer. For me the addition of intensely funereal Hispanic catholic regalia to the usual vampire iconography is a plus, especially when the female vampire first manifests out of nothing in the ornate hacienda rooms in an all-black rig that bespeaks a kind of insatiable piety. What fun.

As for more regular kinds of cinema, I’ll mention just three titles. I caught up with Lorenzo Vigas’s controversial Venice Golden Lion-winner From Afar (which you can read about in Jonathan Romney’s Venice report in our November 2015 issue), and rewatched, necessarily, Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Cemetery of Splendour (see Isabel Stevens’s Cannes report, July 2015), and thought it very fine.

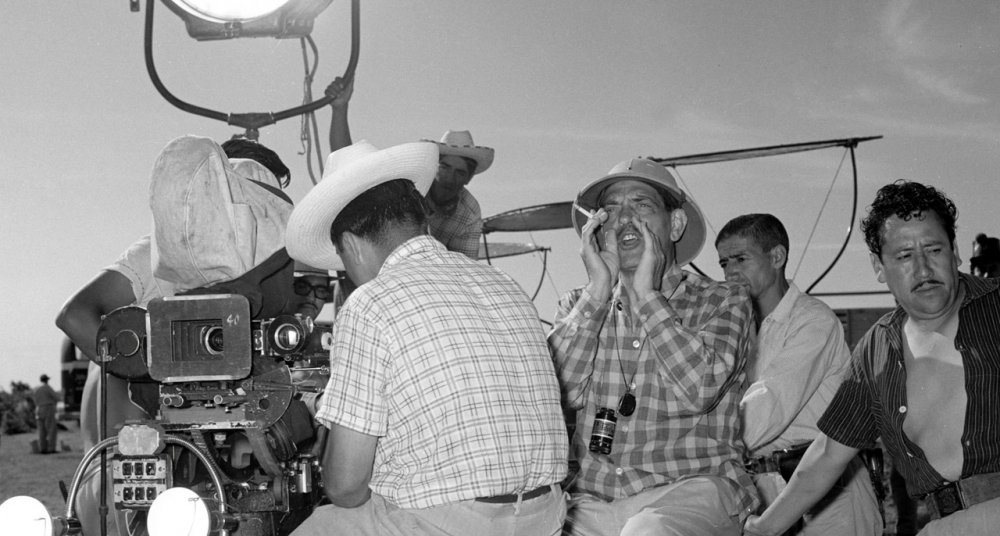

Following Nazarín (Tras Nazarín, 2015)

But the one new film that completely transported me was Javier Espada’s short documentary Following Nazarin, in which the director uses three photographic sources to help retrace the footsteps of Luis Buñuel when he was making Nazarín in Mexico in 1959: Buñuel’s location scouting shots, cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa’s images taken on location and, most particularly, his friend the photographer Manuel Álvarez Bravo’s still images. Espada goes from village to village, interspersing interviews with those who were there at the time and others with a particular view of Buñuel, while his crew painstakingly line up their cameras to reproduce now as exactly as possible the angles and framing used then. The transformation of Mexico recognises a kind of late-coming of industrialisation, particularly in the form of the SUV. So much of the old Mexico has evaporated in the half a century that’s passed that you treasure what’s left all the more, which is exactly what one feels about Morelia itself, a beautiful sixteenth-century Spanish colonial town, and its surrounding region.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.