“Hi. I’ll try to explain what this movie is about,” begins director Mariano Llinás, talking to the camera by a busy country road in a very flat region of Argentina, dominated by structures that ought to support billboards but don’t. The empty monoliths playfully hint that this very elaborate, very long (it will be said over and over, within the film itself and by everyone who writes about it) construction will deliver no message, make no point, merely exist as an endurance test (with intermissions) reinforced by epic-level trolling.

Argentina/The Netherlands/Switzerland 2018

No certificate 808 mins

Director Mariano Llinás

Cast

Episode I

Dr Lucía Conti Laura Paredes

Marcela Elisa Carricajo

Yanina Valeria Correa

La X Pilar Gamboa

Giardina Germán de Silva

Episode II

Pilar Gamboa Victoria Aragón

Flavia Laura Paredes

Andrea Nigro Valeria Correa

Isabella Elisa Carricajo

Ricardo, ‘Ricky’ Héctor Díaz

Frank Alberto Suárez

Episode III

Theresa Pilar Gamboa

Agent 50 Elisa Carricajo

301 Laura Paredes

la niña Valeria Correa

Episode IV

actresses in The Spider Laura Paredes, Valeria Correa, Elisa Carricajo, Pilar Gamboa

director of The Spider Walter Jakob

Episode V

tourist cowboys Esteban Lamothe, Santiago Gobernori

mother Gaby Ferrero

daughter Milva Leonardi

divorced father Matías Feldman

son Ramón Marquestó

Episode VI

Sarah S. Evans Elisa Carricajo

mestizo girl Valeria Correa

mestizo girl’s mother Laura Paredes

creole girl Pilar Gamboa

director of La Flor Mariano Llinás [uncredited]

texting producer of The Spider Laura Citarella [uncredited]

In Colour and Black & White

[1.78:1]

Part-subtitled

UK release date 13 September 2019

Distributor ICA Films

ica.art/films/mariano-llinas-presents-la-flor

► Trailer

Llinás returns at intervals throughout, growing older and shaggier over the nine years the film was in the making, to remind viewers they’re now trapped with his uncontrollable vision. At one point, he mentions that it’s three and a quarter hours until the end of the episode we’re watching (Episode III), whereupon there will still be three more entire segments to go.

The director tells us plainly what we’re in for, but holds back some surprises – such as the 40 minutes of end credits unspooling over an upside-down shot of pampas grass at sunset. This sequence is longer in running time than Episodes V and VI, both of which would feel superfluous or beside the point if anyone had a sense that the film had a single point to be beside. It takes its title from a flower-like sketch Llinás makes to illustrate its form, though this elegance is parodied and deconstructed in a scruffier ‘it’s-a-spider-no-it’s-an-ant’ scribble made by the director’s harassed alter ego in Episode VI.

“There are six stories,” Llinás continues. “Four of them have a beginning but not an ending. That is to say they stop in the middle: they have no ending. Then, there is episode five, which like a short story has a beginning and an end. Finally, there is episode six, which begins in the middle and ends the film. Each episode has a genre, so to speak. The first episode could be regarded as a B movie, the kind that Americans used to shoot with their eyes closed and now just can’t shoot any more. The second episode is a sort of musical, with a touch of mystery.

“The third episode is a spy movie. The fourth episode is difficult to describe. Not even I, in the moment of making this prologue, have a clear idea. The fifth is inspired by an old French film, and the last is about some captive women in the 19th century who return from the desert, from the Indians, after many years. The punchline of the whole movie lies in the fact that all the episodes star the same four women in different roles. Valeria, Elisa, Laura and Pilar. I’d say the movie is about them and, somehow, for them. OK, I think that’s about it – for now…”

Elisa Carricajo as Agent 50, Laura Paredes as 301, Valeria Correa as la niña, Horacio Marassi as Dreyfuss and Pilar Gamboa as Theresa in Episode III

The lede that no one is going to bury is that La Flor is 13 and a half hours long. It’s an anthology movie that wants to be watched in a sitting – like, say, Peter Duffell’s The House That Dripped Blood (1971), which also stretches to a metafictional episode set in the film industry that has yielded the larger film – rather than a series of interrelated movies or TV shows with a shared cast (such as the BBC’s 1972 run of plays The Sextet) that can safely be watched with week-long rests instead of intermissions. The vastly different running times of individual segments resists any packaging of the parts for broadcast – although, in an era of binge-watched streaming shows where 13 episodes drop on the same date to tempt instant addicts, the experience of consuming all of La Flor in one go is not as unusual or challenging as it might have been ten years ago, when the director saw the four main actresses in a stage production and began putting this together as a shared vehicle for them.

Llinás’s film has been so long in the works that the cast age affectingly and with consequences for any career prospects. The fresh-faced ingénues and incipient divas of the first segments, who might have been springboarded into international movie roles if these episodes had been seen shortly after they were shot, are nearly middle-aged character actresses by the latter stages, last seen out of focus through a blur of muslin, cobwebs and dirt in the punitively hard-to-watch Episode VI.

Anything this all-encompassing must make deliberate or accidental connections along the way. That aside about Episode I being the sort of thing Americans can’t make any more must have been delivered long before the Tom Cruise version of The Mummy (2017), which more than validates the observation – though several elements of the piece, including an exorcist called ‘La X’ (‘la Cruz’), seem to be specific digs at that already-forgotten flop. Nearly a conventional horror film, the mummy story here mostly serves to introduce the four lead actresses, and ends with a non sequitur that declares the female mummy to be one of a trio of queens whom we then expect to turn up in later stories… only to be never mentioned again.

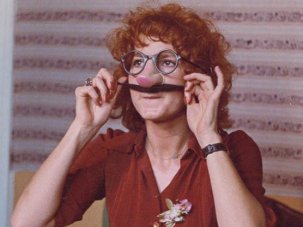

The genre-blending and structural complexity don’t start until the musical episode, which is the first to bend time. Singing duo Victoria and Ricky’s career stretches from a vinyl LP copyrighted 1981 to MP3 players, though they age less over its course than Pilar Gamboa does over the course of the whole project. Later, in a 1980s-set episode, a cross-Channel hovercraft displays a web address on its side, though the Argentinian idea of Thatcher’s Britain – with the PM as a cigar-smoking equestrienne and cadres of posh spies with moustaches out of Hergé – is likely to be seen in the UK as entirely farcical by design.

Episode II carries over from the first episode Llinás’s fondness for tracking shots with his female stars centre-screen. It breaks away from its declared remit as a musical by having Flavia (Laura Paredes) simply take a long walk out of the showbiz storyline, with its tangle of angsty personal-creative relationships and (genuinely effective) song score, into a fantastical plotline involving mad science, scorpion venom, eternal youth and a sinister conspiracy. It’s a priceless moment, and those who aren’t willing to follow the trail out of the film they thought they were getting and into something stranger should probably walk out then, because the tangle becomes a lot more complex and potentially infuriating in the longer, Chinese-box-structured Episodes III and IV. These pile on the flashbacks-within-flashbacks, unresolved storylines, non sequiturs and head-scratching to such a degree that even the director (like his less sympathetic fictional avatar) seems close to cracking up.

The Hergé reference recurs with glimpses of Tintin albums (and a sketch of Tintin’s moon rocket in the director’s notebook), a mummy resembling the creature in The Seven Crystal Balls and an archaeologist who dowses like Professor Calculus. But, as the film wears on, riffling through the labyrinthine complexity of Cold War-era spy fictions in which all agents are at least triple, other literary models become more apparent and there’s a blunt attempt to connect with a gothic-picaresque tradition that boils down to flatly digging out dog-eared copies of Jan Potocki’s The Saragossa Manuscript, William Beckford’s Vathek, Charles Maturin’s Melmoth the Wanderer and Arthur Machen’s The Three Impostors. All of these are characterised by jumbles of tales within tales, doppelgangers, eternal recurrences, vast conspiracies that may also be trivial, pull-backs to reveal the author hard at work, and a feeling that long though they might be they still aren’t finished.

Even when Llinás throws in a black-and-white silent palate cleanser, it’s a remake of Jean Renoir’s Partie de campagne (1936), based on a story by another versatile multi-genre tale-teller (Guy de Maupassant) and – of course – never completed by its director thanks to adverse weather conditions.

At this point, your reviewer must cop to numbed exhaustion and a sense that the director’s trolling tactics go beyond tweaking the audience to keep them engaged and into a fundamental misunderstanding of the psychology of anyone willing (or obliged) to sit for it all. Most of Episode V is blankly silent, a creative decision that suggests technical breakdown – Lord, what if the screening can’t go on and we have to come back and watch the whole thing over again to get to the end? – only to set up a stretch of strange magic as scraps of Renoir’s soundtrack play over beautiful images of an arbitrary air show (maybe using some of the period planes seen in Episode III’s airfield sequence).

One of the little lies salted away in the director’s statement is that the women are in all the episodes. They dominate the first three, but become ‘witches’ (remote, teasing, capricious presences) seen by earnestly befuddled male characters (the director, a parapsychologist, Casanova) in the fourth, are absent from the Renoir homage, and return only as blurs in the coda-like sixth (a minimalist Argentinian western as much as Episode I is an Argentinian mummy movie).

Llinás takes a secondary role in the fiction, as Boris the Mole, in the most extensive flashback of the globetrotting section of Episode III. A traitor unnoticed by the queenly spymistress (Elisa Carricajo), Boris has foreseen and furthered the collapse of the Cold War way of life. Here, Llinás delivers a monologue to a nodding star, whereas the film is otherwise given to letting its actresses handle stage-like speeches of revelation or illustration, often frankly assessing their own roles in the ongoing dramas. “If this were a play, I wouldn’t be the heroine – or even the enemy of the heroine,” muses Victoria’s possible rival Andrea (Valeria Correa). Later, she delivers a monologue about her family background that suggests she is formidable enough to be an antagonist… only to be trumped when the diva responds not with another speech but with a devastating song that paradoxically wins a duel with the punchline “I don’t mind losing.”

In the end, as was said in the beginning, if La Flor is endurable it’s not because of its genre games, M.C. Escher structure or even the occasional well-tailored anecdote, but because of its star quartet, all of whom display presence and range (Gamboa literally goes from supreme voice to mute between episodes, while Carricajo grows in authority from minion to coven leader over a run of stories). We get to know these women and relate intimately to them over the course of the day or so we spend in their company. My impatience with the last two episodes – and those agonising end credits – may be down in part to a sense of loss as the marvellous queens, spies and witches are removed from the pattern, leaving a flower without petals.

-

Sight & Sound: the October 2019 issue

Brad Pitt in James Gray’s Ad Astra, plus For Sama, The Last Tree and R.W. Paul.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.