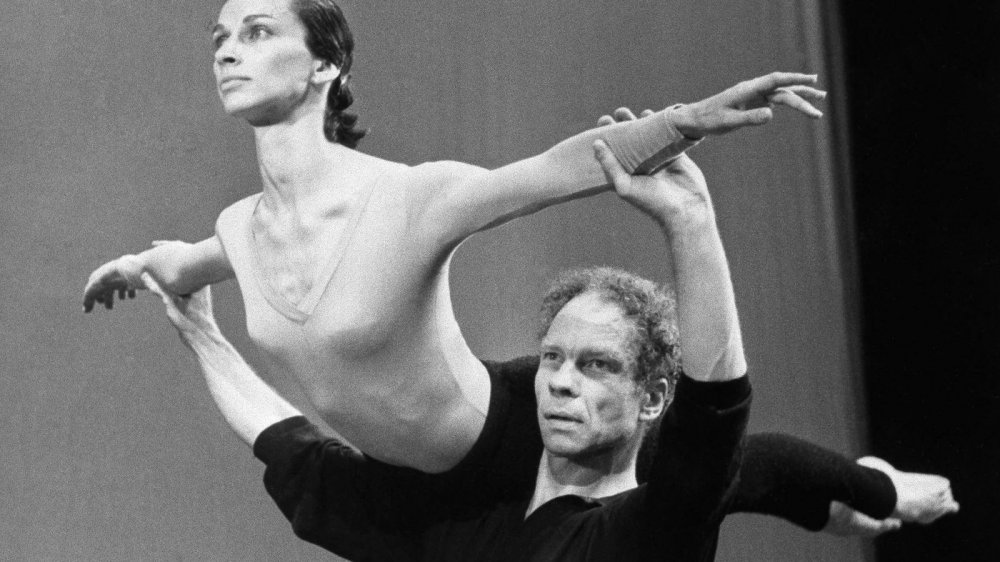

Seven years in gestation, Alla Kovgan’s Cunningham is an atypical biographical documentary, pleasingly devoid of contemporary talking heads. As well as tracing Merce Cunningham’s 70-year journey – which made him modern dance’s Nijinsky and, as a choreographer, the equal of Martha Graham (for whom he danced from 1939 to 1945) and George Balanchine – it captures for posterity brief sequences from 14 of his most challenging pieces. Kovgan restaged them for filming in 3D (echoing Wim Wenders’s Pina in 2011) and, vitally, cast some of the last dancers from Cunningham’s company, which, as he had wished, disbanded in 2011, two and a half years after his death and 58 years after its foundation.

Germany/France/United Kingdom/USA/The Netherlands/Belgium 2019

Certificate U 92m 34s

Director Alla Kovgan

[1.78:1]

Some screenings presented in 3D

UK release date 13 March 2020

Distributor Dogwoof

cunninghamfilm.co.uk

► Trailer

Those of the new performances that replicate Robert Rauschenberg’s sets and costumes – a pointillist backdrop (originally spray-painted by Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns) which the dancers in their spotted bodysuits seem to emerge from and fade into (Summerspace, 1958); a dangerous faux freeway strafed by the lights of speeding cars (Winterbranch, 1964) – emphasise Cunningham’s technically complex and discomfiting movements. Influenced by his interest in anthropology, they radiate chaos and existential isolation, which he was disinclined to discuss. Dancer Sandra Neels says that Cunningham’s claim he was just creating steps simply wasn’t true.

In contrast, Kovgan’s recreation of Cunningham’s Shards (1987) on a Manhattan rooftop and Suite for Two (early 1950s) in an ornamental park are marred by, respectively, the camera’s grandiose perspective from a circling helicopter and a shot that draws back from the duetting dancers over a pond and (via an indoors scene) ostentatiously dollies over the water.

There’s similar fussiness in the biographical sequences, which deploy split screens and angled frames (with rounded edges) within frames; priceless colour footage of Cunningham’s dancers in the 1950s is annoyingly split into six moving images. Pretty animal illustrations placed beside stills of the company on the road in the early days are as distracting as bits of separate footage appearing nonsensically within strips of celluloid.

A Moscow-born interdisciplinary artist who has filmed four previous dance documentaries, Kovgan presumably wanted Cunningham to be more expressive than, say, the visually conservative biographical documentaries made for PBS’s American Masters series, but greater simplicity would have improved the film. It’s hard enough for the layperson to comprehend Cunningham’s choreographic process – dependent on meticulousness and randomness, the combining of legato and staccato movements – and his counterpointing of John Cage’s dissonant music.

As for human drama, Cunningham leaves questions unanswered: why did Rauschenberg rudely sever his collaboration with artistic soulmates Cunningham and Cage in 1964? How did the company survive a crisis that left its coffers nearly empty?

Flaws aside, this is an invaluable primer for modern-dance neophytes, while Cunningham devotees should love it.

-

The 100 Greatest Films of All Time 2012

In our biggest ever film critics’ poll, the list of best movies ever made has a new top film, ending the 50-year reign of Citizen Kane.

Wednesday 1 August 2012

-

The best films now on UK streaming services

Looking for the best new cinema releases available on British VOD platforms? Here’s our guide to how to keep up with the latest movies while you’re...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.