The possibility of an ideal film bookshelf is always intriguing: that along a single shelf you could fit the most inspirational books everyone interested in film needs to read – particularly anyone just starting their adult cinema adventures. Before we conducted our survey, I thought I knew which books were most likely to sit snugly on that shelf. That certainty was allied to a strong suspicion that the field of film literature already had its own Citizen Kane in David Thomson’s A Biographical Dictionary of Film.

But our film books survey did not turn out quite as I assumed. We asked a number of critics to choose the five film books that have proved most useful and/or inspirational and/or important to them. Typically they named a vast array of volumes between them, but while it was satisfying to note that so many of the chosen books were on Sight & Sound’s own shelves, many more were not.

Halfway through our survey, it looked as if Thomson’s Biographical Dictionary would be a clear winner. As the last entries came in, however, five works emerged that are more or less equally loved and admired, standing clear of the rest of the field and with just three votes (or mentions) separating first from last. They are André Bazin’s What is Cinema?, Robert Bresson’s Notes on the Cinematographer, Andrew Sarris’ The American Cinema, Thomson’s Biographical Dictionary and François Truffaut’s Hitchcock.

On one level, this emergent armful is pleasingly diverse: respectively these five books are a theoretical work, a collection of aphoristic declarations, an opinionated survey of the dominant cinema, a personality-centred dictionary and a book-length interview. As it happens, Thomson’s great book did just edge first place – by two votes – but then the Biographical Dictionary is still in a class of its own, and not only because it is written so juicily and informs so fulsomely. Being about personalities and heady with dynamic speculation about their nature, the Biographical Dictionary evades the self-defeating air that makes too many film books seem superfluous: that knowledge that you can’t enjoy them without constant reference to the films they mention. Just as we can read, for instance, Samuel Johnson’s Lives of the Poets for the pleasure of its wit without much knowledge of the subjects’ poetry, so Thomson’s entries are fascinating no matter what our knowledge of the chosen protagonist or their works – though of course the deeper our understanding, the more enjoyable the miniature portraits become.

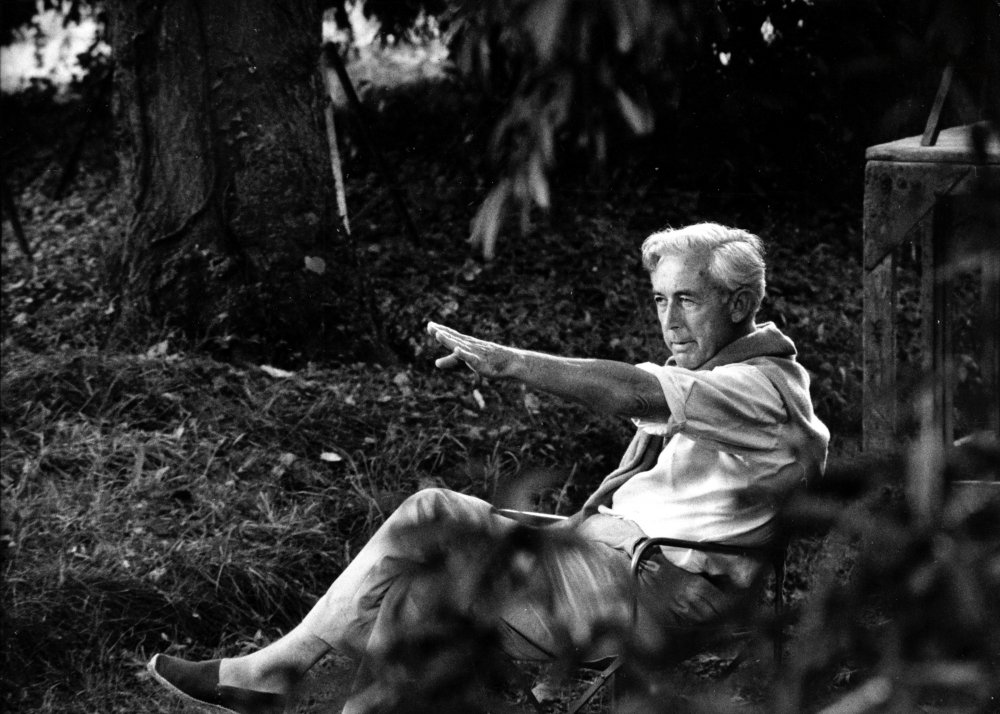

Robert Bresson directing Au Hasard Balthazar (1966)

With its aura of gnomic quasi-religious utterance, Bresson’s Notes on the Cinematographer is more dependent on prior cinema knowledge. It requires the reader to know what Bresson means, for instance, by the term ‘model’ – the type of non-professional performer whom Bresson always preferred to real ‘actors’. “The thing that matters,” he writes, “is not what they show me but what they hide from me and, above all, what they do not suspect is in them.” Though his remarks are randomised in subject throughout, if you group the similarly themed together, an argument emerges. “To create,” he writes, “is not to deform or invent persons and things. It is to tie new relationships between persons and things which are as they are.” The impression is of Bresson building a dry stone wall from oddly shaped flints and rocks. Once these aphorisms are set together, the work will withstand decades of sceptical wind.

Bazin’s two volumes (in the English translation) of What is Cinema? constitute the serious critics’ bible. Here the most fundamental questions about the language of cinema and its relationship to the other arts are thoroughly worked through. One emerges from reading his collection of essays with a fresh clarity of thought about the medium, as if Bazin’s perspicacity were infectious. Of course, many of Bazin’s ideas find their way into Sarris’ thoroughgoing, well-argued survey The American Cinema, with its explanation, Americanisation and adjustment of the politique des auteurs, and its categorisation of directors under semi-witty rubrics such as ‘Less Than Meets the Eye’, ‘Lightly Likeable’ and ‘Strained Seriousness’.

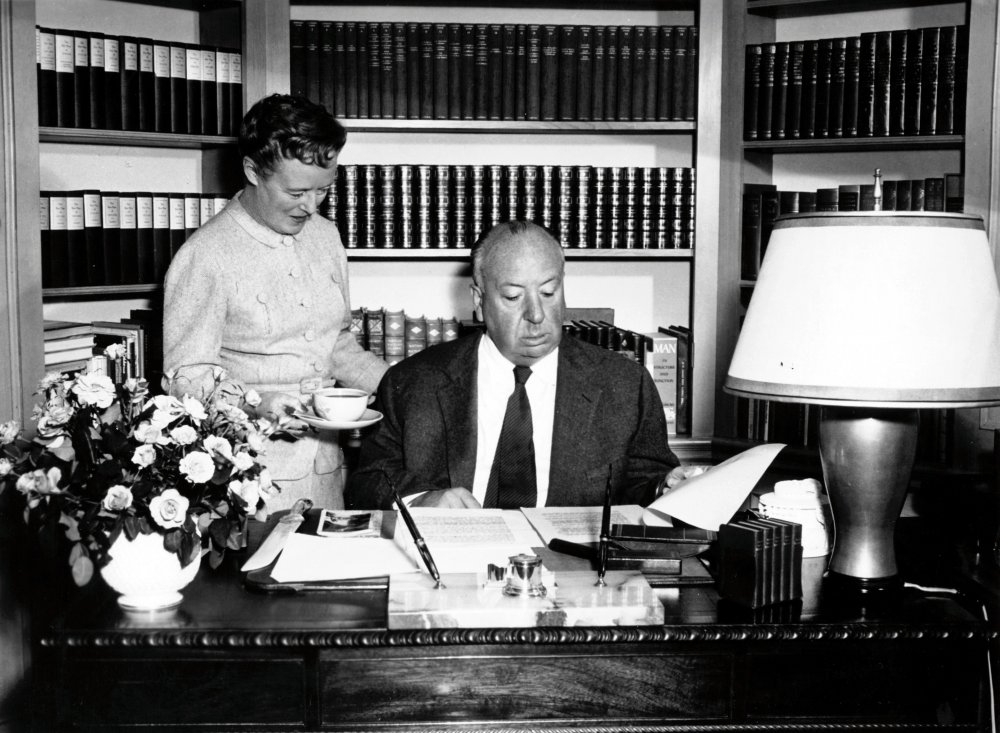

For a free-ranging conversation about the how and why of making as perfect a form of cinema as possible, there’s nothing to touch the transcript drawn from 50 hours of recorded conversations that went into François Truffaut’s book Hitchcock. Uncharacteristic candour is on display from Hitchcock here. Truffaut coaxes a fascinating aural history of linked anecdotes from him, as well as a compendious problem-solving masterclass in film practice. Hitchcock’s precise and exacting mind, his well-honed storytelling skills and his professional certainties are all properly engaged throughout.

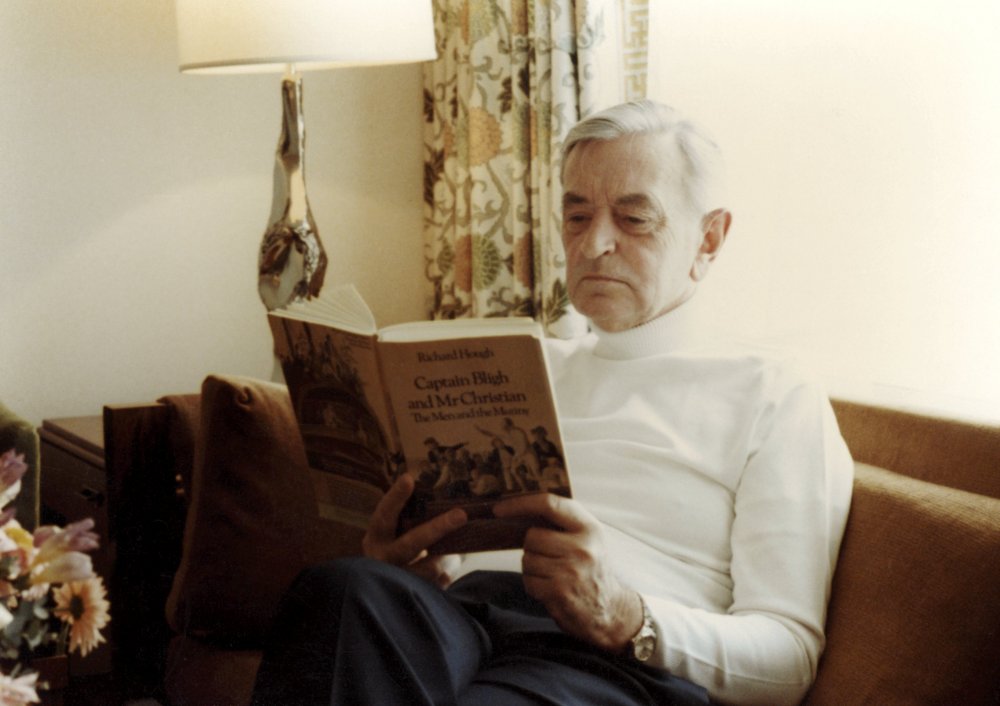

André Bazin

Two things link these five outstanding books: first, they were more or less all first published between 1965-1975 (although, to be clear, the first Bazin volume of four in French was published in 1958, the last in 1962; the two English-language volumes in 1967 and 1971): second, nearly all of them are either derived from or were inspired by Bazin’s cohort at Cahiers du cinéma.

Such a ‘golden age’ manifestation might be down to us asking too many critics of a particular generation to take part. As with films themselves, a cinema lover’s favourite film books tend to be those they discover when young. However, another factor counts here: before the advent of video and DVD, the film book had a different function. If writing and still images can sometimes seem a poor substitute for the cinema they refer to, we must not forget that, in the days when cinephiles had to wait for historic films to be screened, film books were a necessary aide-memoir to great experiences that were hard to re-experience.

On the other hand, since films themselves originate from script and storyboard or shot list, and the Cahiers crowd in particular argued in support of such concepts as the camera stylo (the camera that writes like a pen), the film book of text and still images might have achieved a higher status. How far away from a really good visual film book, for instance, is Chris Marker’s photo roman La Jetée? Not all that far, and new technology will bring the two closer yet.

All this richness makes one wonder why an inferiority complex seems to surround film books. They suffer in positional terms in bookshops not only because all arts books are hard to sell but perhaps also because they’re more multifarious in sub-categories than other book genres. They’re also too extended in their pop-to-avant-garde cultural range, and theory-to-practice reference range to create a coherent appeal.

Perhaps this lack of confidence in the film book is both a post-DVD phenomenon and a consequence of the plenitude of film book titles in a field that was once so sparse. It may explain, too, why so many books I was expecting to be mentioned in our survey didn’t appear.

Where, for instance, is Carol J. Clover’s key work on horror Men, Women and Chainsaws, with its significant observation about the teenage boy’s identification with the ‘final girl’? Where is David Bordwell’s recent The Way Hollywood Tells It, which argues that, despite the apparent newness of approaches, film narrative techniques have not changed much since Griffiths’ days? The most famous film book in the UK when I was growing up was Halliwell’s Film Guide; it gets no mention here, and the Time Out Film Guide gets just one passing mention (perhaps because it dropped the invaluable subject index – the most useful thing in it – from recent editions). In fact, you could conclude from this survey that the Film Guide format no longer cuts any ice, if it ever did, with critics.

Gilles Deleuze’s Cinema 1 and Cinema 2, which famously distinguish between the ‘time image’ and the ‘movement image’, have not featured. Jonathan Rosenbaum’s cri de coeur about the victory of marketing over criticism, Movie Wars, doesn’t make it either, and nor does Movie Mutations, a seminal collection of late 1990s zeitgeist conversations between Adrian Martin, Kent Jones, Alexander Horwath, Nicole Brenez, Raymond Bellour and Rosenbaum.

David Lean

Some whole subject areas, too, get short shrift. Documentary is not represented – the Faber collection of writings that Mark Cousins and Kevin MacDonald edited, Imagining Reality, should have got a look in, as should Brian Winston’s polemical history Claiming the Real or maybe Michael Chanan’s The Politics of Documentary. Cinematography also doesn’t seem to have an urtext to call its own (Bresson’s book is not about camerawork per se, but about directing in general), though we might have expected at least one vote for John Alton’s Painting with Light.

But what we do have is more than enough fascinating volumes to tumble from an overflowing bookcase. And if Thomson’s Biographical Dictionary didn’t dominate as I thought it would, that won’t prevent me giving it the pride of place its two-vote victory deserves.

Opening a page at random gave me the entry for Peter Lorre: “Lorre is one of the great screen personalities, no matter that he had so few leading roles. Perhaps he was a genius frustrated by the various sanities and insanities of the world. But perhaps he came very close to the nature of film with his extraordinary combination of impact and nonsense. He hardly seems dead, just as it is difficult to believe he was ever clinically alive.” The comments that follow have their share of impact and nonsense, but the film book seems to be as alive as it ever was.

☞ See the top five

☞ See the full poll

- Sight & Sound reviews the latest film books every month.

—

Correction (4 May 2010): Icelandic volcanic ash clouded our proofing (and counting) systems as we finalised this article. The original online version claimed that A Biographical Dictionary of Film led our poll by one vote, with just two votes separating first from fifth. Thomson’s book in fact led by two votes, and the gap from first to fifth was three mentions. This has been corrected above.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.