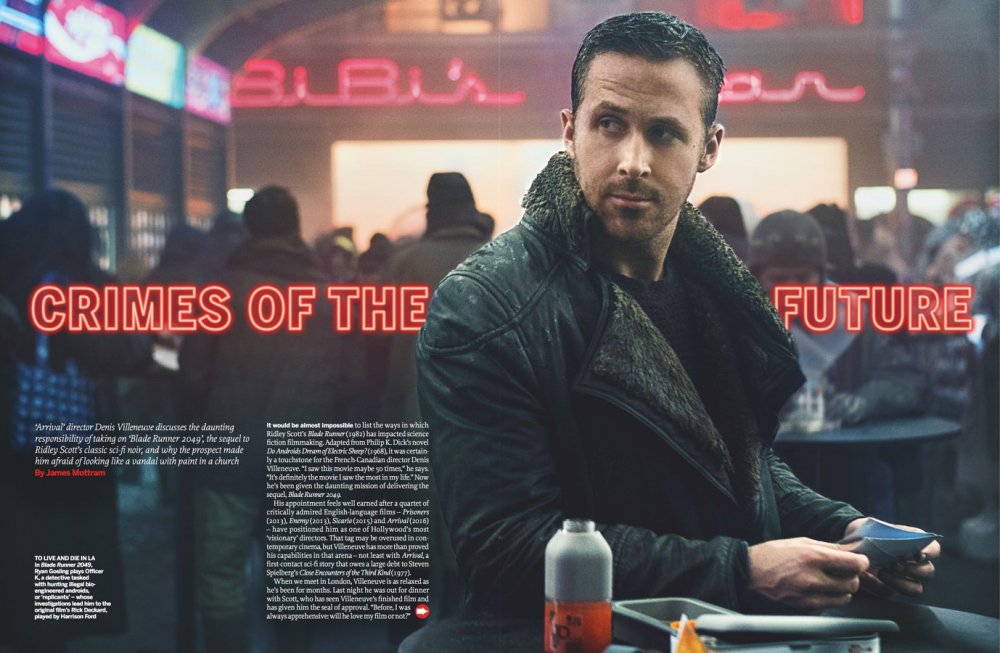

“I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe”, says Rutger Hauer’s replicant Roy Batty in his famous monologue in Ridley Scott’s hugely influential 1982 sci-fi noir Blade Runner, adapted from Philip K. Dick and set in a dystopian Los Angeles of 2019. Well, we’ve now nearly caught up with the time shown in that film, and if we still haven’t in reality seen many of the futuristic visions it depicted – the dystopian feel of much of the world in 2017 aside, flying cars are still a way off – its influence on science-fiction cinema since has been incalculable and inescapable. So great in fact is the original’s influence, and so confirmed its reputation as a sci-fi masterpiece, that it’s perhaps unsurprising it has taken 35 years before a filmmaker has ventured back into its world, for fear of failing by comparison. But that’s exactly what the French Canadian director Denis Villeneuve has dared to do with his sequel Blade Runner 2049, even if, as he admits to James Mottram in an interview in our new issue, “I was afraid of looking like a vandal in a church!”

Posted to subscribers and available digitally 6 October

→ Buy a print issue

→ Access the digital edition

→

On UK newsstands 10 October

With the reviews now in, though, Villeneuve needn’t have worried, for his vision of the world 31 years from now is an astonishing one. Villeneuve tells Mottram how he worked with the great cinematographer Roger Deakins to achieve the striking look of the film, how he and his star Ryan Gosling overcame their nerves and embraced the freedom the studio gave them in making the film, how the original’s mood of existential paranoia carries over to the sequel and how the spirit of the 80s is still there in his film. Back to the future indeed.

If Villeneuve’s film captures and updates the mood and feel of film noir, another director famous for his innovatory spins on the tropes of noir, and for his meticulous approach, is David Fincher, whose new 1970s-set Netflix series Mindhunter begins this month. With Mindhunter marking a return to the world of serial killers and the men who try to catch them that Fincher explored in Se7en and Zodiac, he talks to Simran Hans about his interest in “confronting something that should be abhorrent”, and how the way the show depicts the genesis of behavioural profiling in the FBI in the 1970s allowed him to get back to a time before such law-enforcement characters had become prime time staples.

Staying in a paranoid, 1970s world, and to mark their screening as part of Who Can You Trust?, the major thriller project the BFI is running from mid-October to the end of the year, Adam Scovell looks again as Alan J. Pakula’s era-defining ‘paranoia trilogy’ – Klute, The Parallax View and All the President’s Men – and finds that their bland, air-conditioned corporate locations perfectly capture the threats of surveillance in the 70s, as well as having cautionary lessons for us in the present.

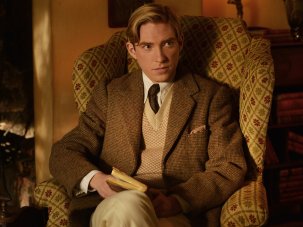

But it’s far from all anxiety-ridden in the new issue, as we also speak to Italian director Luca Guadagnino about his exquisite coming-of-age love story Call Me by Your Name, about a passionate summer affair between two young men, played by Timothée Chalamet and Armie Hammer. Guadagnino tells Pamela Hutchinson why the film is a homage to the cinema he loves, and also discusses his great debt to his idol Bernardo Bertolucci.

And we also make room this month for humour of the most viciously funny kind, as Ben Walters talks to Armando Iannucci about his brilliant new film The Death of Stalin, a hilarious portrait of the jockeying for power that follows the demise of the dictator, and one that bears all the hallmarks of the satirical genius of director. Though set in the 1950s, and therefore somewhat of a departure for a writer and director best known for skewering the foibles and vanities of contemporary politics in shows such as The Thick of It, in showcasing a gallery of slightly rubbish people insulting each other in a hurry, it is on the other hand as timely and as incisive as we’ve come to expect from Iannucci.

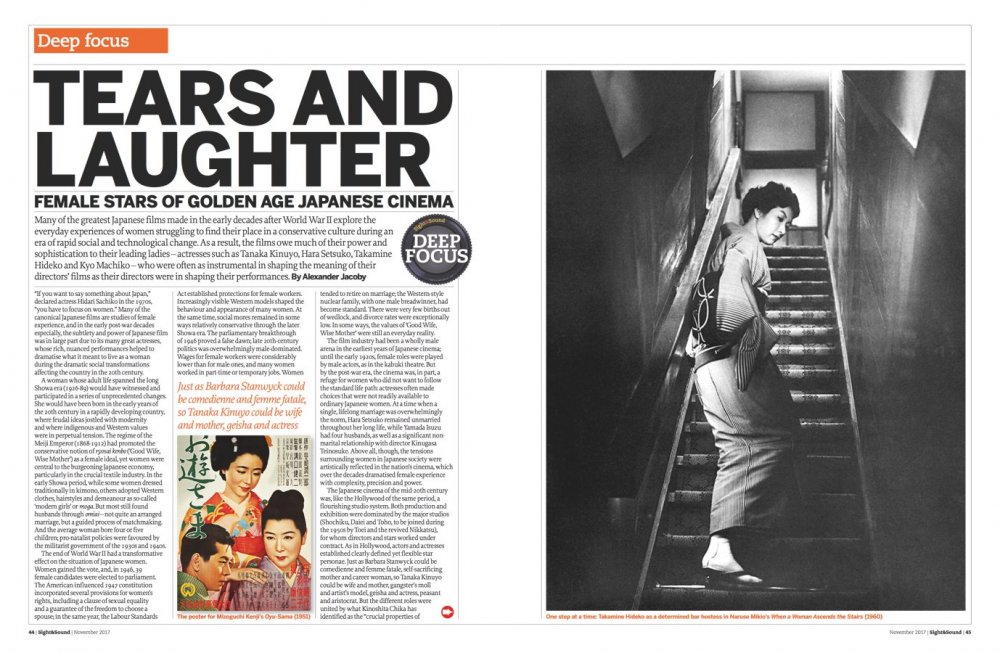

Lastly for this month’s features, and in the latest of our ongoing Deep Focus features that tie-in with accompanying programmes organised by Sight & Sound at BFI Southbank, we spotlight the great female stars of post-war Japanese cinema – figures such as Hara Setsuko, Tanaka Kinuyo, Takamine Hideko and Machiko Kyo, and the many classic films they starred in for directors such as Ozu Yasujiro, Naruse Mikio and Mizoguchi Kenji. Alexander Jacoby shows how such female actors were instrumental in shaping their films, while Alejandra Armendáriz-Hernández looks at the pioneering work Tanaka Kinuyo did as a director, alongside her acting career.

Elsewhere in the November issue, we review the best new film’s from the recent Venice and Toronto film festival. Grace Barber-Plentie meets Rungano Nyoni, director of satirical fairy tale I Am Not a Witch; Sukhdev Sandhu admires the radical, gradual documentaries of John Gianvito; Tony Rayns reveals the enigmas of Indonesian filmmaker Garin Nugroho; Elena Gorfinkel peers under the covers of 60s sexploitation films – and finds them cheap, crass and surprisingly artful; and Pamela Hutchinson discovers the charm of Betty Balfour, urchin star of the 20s and 30s.

We review all the new theatrical releases of the month, including Yorgos Lanthimos’s The Killing of a Sacred Deer and Sally Potter’s The Party, and in our Home Entertainment section Henry K. Miller sweats through a new Blu-ray collection chronicling Jean-Luc Godard’s shift from purist director to Maoist ideologue. And our book reviews take in a memoir of Dietrich by her daughter and a new study of 1940s Hollywood.

All this and more. So much indeed, that there are ‘things you people wouldn’t believe’…

Features

Crimes of the Future

Arrival director Denis Villeneuve discusses the daunting responsibility of taking on Blade Runner 2049, the sequel to Ridley Scott’s classic sci-fi noir, and why the prospect made him afraid of looking like a vandal with paint in a church. By James Mottram.

The Air-Conditioned Nightmare

The bland, sinister corporate locations used by Alan J. Pakula in his era-defining paranoia trilogy – Klute, The Parallax View and All the President’s Men – perfectly capture the threats of everyday surveillance and political conspiracy in the 1970s. By Adam Scovell.

My Summer of Love

Luca Guadagnino’s exquisite coming-of-age love story Call Me by Your Name explores a passionate summer affair between two young men. Here the director explains why the film is a homage to the cinema he loves and discusses his debt to his great idol Bernardo Bertolucci. By Pamela Hutchinson.

Killer Instinct

David Fincher’s Netflix series Mindhunter explores the genesis of behavioural profiling in the FBI in the 1970s. The director talks with Simran Hans about psychosexual sadism and how to make sense of people who like cutting up hitchhikers.

Room at the Top

The Death of Stalin, a viciously funny portrait of the jockeying for power that follows the demise of the Soviet dictator, bears all the hallmarks of the satirical genius of its director Armando Iannucci, showcasing a gallery of slightly rubbish people insulting each other in a hurry. By Ben Walters.

Tears and Laughter: Female Stars of Golden Age Japanese Cinema

Many of the greatest Japanese films made in the early decades after World War II explore the everyday experiences of women struggling to find their place in a conservative culture during an era of rapid social and technological change. As a result, the films owe much of their power and sophistication to their leading ladies – actresses such as Tanaka Kinuyo, Hara Setsuko, Takamine Hideko and Kyo Machiko – who were often as instrumental in shaping the meaning of their directors’ films as their directors were in shaping their performances. By Alexander Jacoby.

Regulars

Editorial

Rushes

Our Rushes section

Autumn television highlights

Interview: I put a spell on you

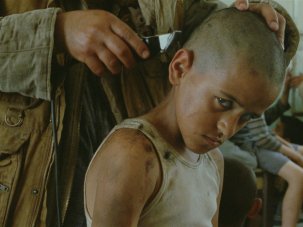

In her first feature I Am not a Witch, Zambian Welsh director Rungano Nyoni has created an angry and darkly funny fairytale about witchcraft in Africa. By Grace Barber-Plentie.

The numbers

God’s Own Country and British gay-male-themed titles at the UK box office. By Charles Gant.

British cinema: Stats of the nation

The numbers are in, and the figures for women in feature film production are predictably dismal – but that’s not the whole story. By Pamela Hutchinson.

Dispatches: Jeanne genie

After years of detective work, 24 lost African classics are screening at film festivals around the UK there’s no excuse not to dive in. By Mark Cousins.

Festivals

Our Festivals section

Venice: creature comforts

Despite an enticing line-up, Venice failed fully to catch fire this year, though a trio of fabulous films helped lift the spirits. By Nick James.

Toronto: trouble in paradise

Even with the number of films cut by a fifth at Toronto this year, there was an embarrassment of riches but a few key problems remain. By Tom Charity.

Wide Angle

Our Wide Angle section

Preview: A taste of flesh

The US sexploitation flicks of the 60s were quick ways of turning a buck – and sometimes, too, funny, artful and audacious. By Elena Gorfinkel.

Preview: Slow burn

Patient and unsensational, the documentaries of John Gianvito reveal the indifference to suffering that underlies global power. By Sukhdev Sandhu.

Primal screen: Cross-border appeal

Betty Balfour, whose cheerful energy helped her survive the transition to talkies, was the star at a Leicester banquet of silent films. By Pamela Hutchinson.

Profile: fantastic voyage

With their echoes of expressionism and traditional Indonesian forms, Garin Nugroho’s enigmatic films take cinema back to its beginnings. By Tony Rayns.

Reviews

Films of the month

Dina

The Killing of a Sacred Deer

Marjorie Prime

The Party

plus reviews of

Our Reviews section

American Assassin

American Made

The Ballad of Shirley Collins

Borg vs McEnroe

Breathe

Call Me by Your Name

The Death of Stalin

Deliver Us (Libera Nos)

Double Date

The Exception

Goodbye Christopher Robin

Grace Jones: Bloodlight and Bami

The Graduation

I Am Not a Witch

Ingrid Goes West

It

Jungle

Kingsman: The Golden Circle

Loving Vincent

The Merciless

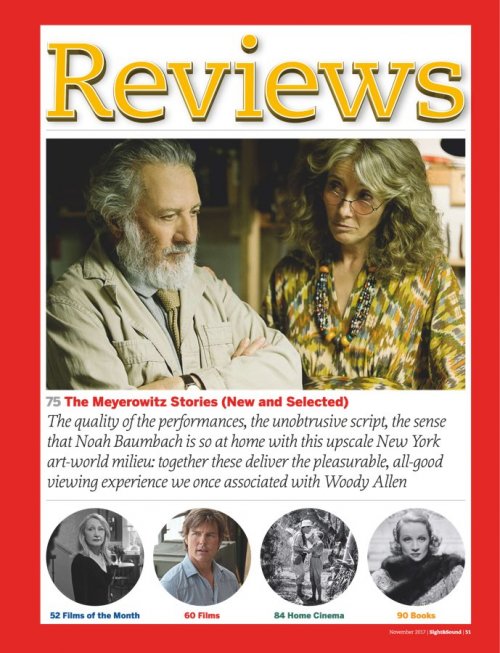

The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected)

mother!

The Mountain Between Us

My Pure Land

Our Last Tango

The Ritual

78/52

6 Below

Thelma

Unrest

Victoria & Abdul

Home Cinema features

Our Home Cinema section

Nobody said it was going to be fun: Jean-Luc Godard + Jean-Pierre Gorin: Five Films, 1968-1971

+ Tout va Bien

The films Jean-Luc Godard made with Jean-Pierre Gorin stand as monuments to leftist political commitment. But why watch them? By Henry K. Miller.

Rediscovery: Every Picture Tells a Story: the Art Films of James Scott

In a body of work made about and in collaboration with artists, James Scott hinted at the British New Wave that never was. By Henry K. Miller.

Lost and found: Demon Lover Diary

Joel DeMott’s account of the making of a no-budget horror flick is a bitingly funny lost classic of documentary history. By Isabel Stevens.

plus reviews of

L’Argent

Marion Davies films: The Bride’s Play / Beauty’s Worth / When Knighthood Was in Flower

The Love of a Woman

The Mourning Forest

Peppermint Soda

Ronin

The Sinbad Trilogy: The 7th Voyage of Sinbad / The Golden Voyage of Sinbad / Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger

The Tree of Wooden Clogs

Television

Sykes

Here’s Harry

Ivanhoe

Books

Marlene Dietrich: The Life, by Her Daughter by Maria Riva (Pegasus Books) reviewed by Pamela Hutchinson

Reinvening Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling by David Bordwell (University of Chicago Press) reviewed by Tony Rayns

Ben Rivers: Ways of Worldmaking edited by Bettina Steinbrügge and Ben Rivers (Mousse Publishing) reviewed by Jordan Cronk

Julien Duvivier by Ben McCann (Manchester University Press) reviewed by Ginette Vincendeau

Our Endings section

Letters

Endings

Eve’s Bayou

Kasi Lemmons’s tale of infidelity, voodoo and murder in the Louisiana bayous shows history has as many shades as witnesses. By Kelli Weston.

Further reading

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.