“There was no excruciating agony,” says one of the survivors of the Jiabiangou labour camp in Wang Bing’s latest documentary, Dead Souls. “People just… passed away.”

Dead Souls screens at the Irish Film Institute 15-16 December 2018, at HOME Manchester on 10 February 2019, and at the Tyneside Cinema 16-17 February 2019.

A Wang Bing retrospective, The Landscape of Chinese Everydayness, is streaming on Doc Alliance.

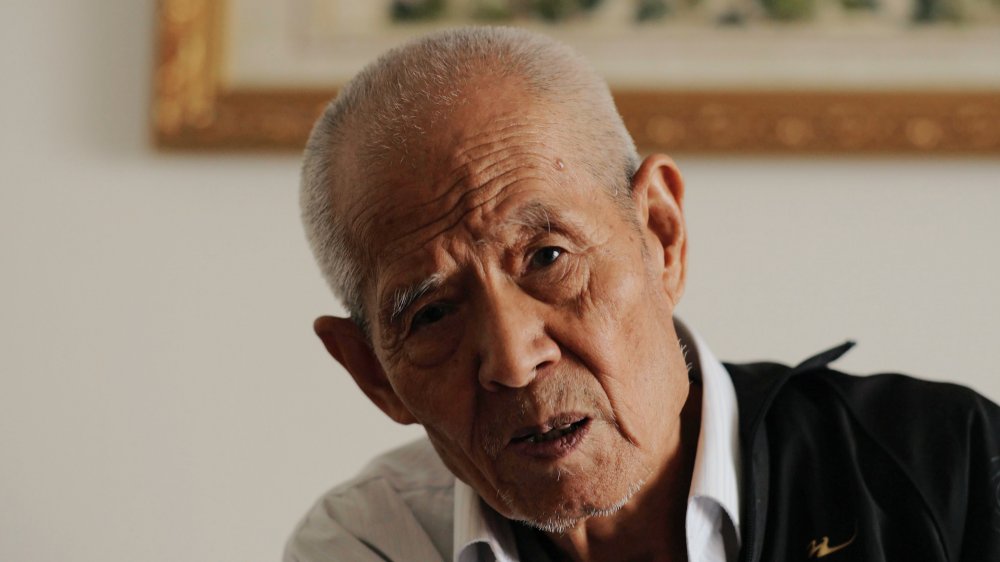

Opinions differ on this point. Much of the film is devoted to harrowing descriptions of conditions of the camp, where ‘rightists’ were sent to be ‘re-educated’ between 1957 and 1961, during Chairman Mao’s Anti-Rightist campaign. Filmed between 2005 and 2017, the 20 subjects of the film range between 70 and 96 in age. They are almost all men: women are actively quieted or simply remain silent (though the last speech, given by a widow, is particularly memorable). The testimonies are lengthy, with Wang giving each survivor around 20 minutes of uninterrupted screen time. If Wang didn’t think this period of China’s history was excruciating, the film would probably not be eight hours long.

Tracking down the survivors wasn’t easy. “There was no contact between them,” Wang told me, though several of them do refer in the film to each other or the same people. “Quite often I received addresses, but very vague ones. We would arrive in an area and look and ask around, and often we couldn’t find the person [we were seeking]. When we did, we started shooting immediately – we didn’t have time to spare.”

Dead Souls (2018)

This wasn’t only because of the age of the survivors. “These people were often under pressure – from family, from the society, from the neighbourhood – and sometimes they were willing to talk about it, but they couldn’t talk for long.”

It is testament to Wang’s character that he extracted such vivid, painful, no-holds-barred memories from people he’d only just met. He has been capturing honest human behaviour since his first film, the nine-hour documentary West of the Tracks (2003), which chronicled de-industrialisation and forced relocations in north-east China. In person he seems instantly trustworthy. It isn’t just his straightforward, unfussy manner; it’s also his shyness. Physically he is unremarkable – a little short, neither large nor skinny, no distinguishing features. He’s a serious man, but when he smiles, everyone smiles. Right away he comes across more as a listener than a talker.

Wang puts it another way. “If my presence were that of a journalist or a TV station, these people would not behave so naturally. I’m just an individual, making my film… most of the [interviewees] are very natural, honest and kind. They don’t make too much fuss about [there being] a camera. They don’t think about it.”

Fengming, A Chinese Memoir (He Fengming, 2007)

In many ways, Dead Souls feels like a culmination for Wang. It is the third time he has attempted to tackle the subject of Jiabiangou. He approached the subject first in Fengming: A Chinese Memoir (2007), a three-hour documentary relating the post-1949 story of memoirist He Fengming, and second in The Ditch (2010), Wang’s only fiction film to date. Formally, Dead Souls is like an extension of Fengming, which involved a single-camera setup and selections from two lengthy interviews with Fengming.

If the narratives Fengming weaves have a rehearsed, almost literary quality, it is because she had already committed them to paper. The survivors in Dead Souls seem to be reliving their trauma openly for the first time – and yet the 20 that make it into the film, from the 120 that Wang interviewed in total, speak with remarkably fluency. Even well into their 80s, they do not ramble or waffle. They daub the ethically barren landscapes they paint with almost casually devastating details, sometimes straining to recall the names of their more unfortunate peers before abruptly exclaiming them with a mixture of relief, regret and triumph. “What was the name of the guy that got eaten?” one man asks his friend, before suddenly remembering.

Wang’s fight against cultural amnesia curiously reflects his own worsening memory. “When he filmed Three Sisters (2012),” his editor Adam Kerby told me, “it was high up in the mountains… running around with the camera, he got some kind of altitude sickness that gave him vertigo. That lasted one or two years. Hospitals couldn’t find anything wrong, but since then his memory’s been bad.”

Three Sisters (San zimei, 2012)

In Dead Souls, Wang, despite seeming like a shuffling, chain-smoking everyman, is as sharp as a knife. In a formal departure for him, he occasionally sits in front of the camera to interview his subjects. When a journalist at Cannes asked him about this, his answer was typically prosaic: “[I made my previous documentaries] alone, and so I would have to carry the camera – so then I wouldn’t appear on screen… [also, this time] I really wanted to be able to focus on the interviews… so I asked someone else to film.”

Master of his material, he points out his interlocutors’ occasional inconsistencies by asking them again about the date they just invoked or the locale they just mentioned. But his quietude and respect acknowledge that despite some factual solecisms and lacunae, there is a greater truth at stake. “This [method] of filmmaking,” he says, “allows you to record faithfully what you see and [how people behave]… the truth and what kind of truth you’re going to show should be the biggest concern.”

Dead Souls (2018)

For the most part, the camera is so static that it sometimes forgets to follow its subjects when they get up out of their chair. It makes the film’s climax – a furious ambulatory handheld take in which we stomp around the site of the former Mingshui complex, pausing for about half a minute every half a minute to stare at the anonymous human skulls that still litter the ground – all the more chilling. The very final shot, with the frame blacking out mid-stride, suggests a story that will never be complete.

Except that it probably doesn’t – or at least, Wang doesn’t see it that way. In a 2017 interview, he said in response to a perfectly reasonable question about his unresolved endings: “I understand what you are getting at, but personally I don’t want to make any metaphor out of my open endings.” When I ask him whether his films’ structures emerge during pre-production, shooting or editing, he replies that he will “quite often have a vague idea of the structure while doing the shoot. Of course, when the shooting’s finished, it’ll depend on the footage I got.”

Wang is a realist to his core, yet his films do generally have a structure – take the tripartite societal analysis of West of the Tracks or the near-Bildungsroman narrative of Fengming. Even his less interesting films have some narrative framework: the migrant documentary Bitter Money (2016), for instance, follows a vague loss-of-innocence arc.

Bitter Money (Ku Qian, 2016)

There is a structure, of sorts, at work in Dead Souls. The testimonies are told in a sort of geographical order, and the film’s final fifth groups together the widow, the handheld climax and an affecting written sequence featuring the letters of a man who perished in the camp. Nonetheless, the lack of formal variety over the first 450 minutes can be stultifying.

The only time during this stretch that Wang departs from simply filming the survivors’ testimonies, one after the other, is when he films the funeral of one of the Jiabiangou survivors. It is truly a heartrending scene: the deceased’s son reads, with growing passion, a lengthy dithyramb to his dead father, excoriating the systems that mistreated him, thanking him for always putting his children first, and crying out in hope for future generations. And while the scene’s insertion makes sense chronologically – it comes right after footage of the survivor in his final years – its position amid seven and a half hours of straight testimony does not quite cohere.

Of course, theoretical justifications can be made for the film’s longueurs: the fact that the testimonies often repeat each other gives the oral history a cumulative, corroborative force; the stillness of the camera has a hypnotic effect; the film’s formal uniformity for the first 450 minutes makes the specific horrors of each individual’s experience all the more memorable. But these don’t necessarily translate in praxis, or make for a cinematically satisfying experience. Even if you watched it in four two-hour chunks, you’d need strong powers of concentration, particularly during the comparatively less interesting first half, to hang on to the testifiers’ every word. Which of course raises the question: what right have we to expect cinema from a series of long-suppressed historical testimonies?

Dead Souls (2018)

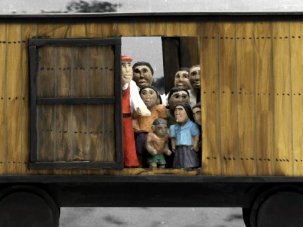

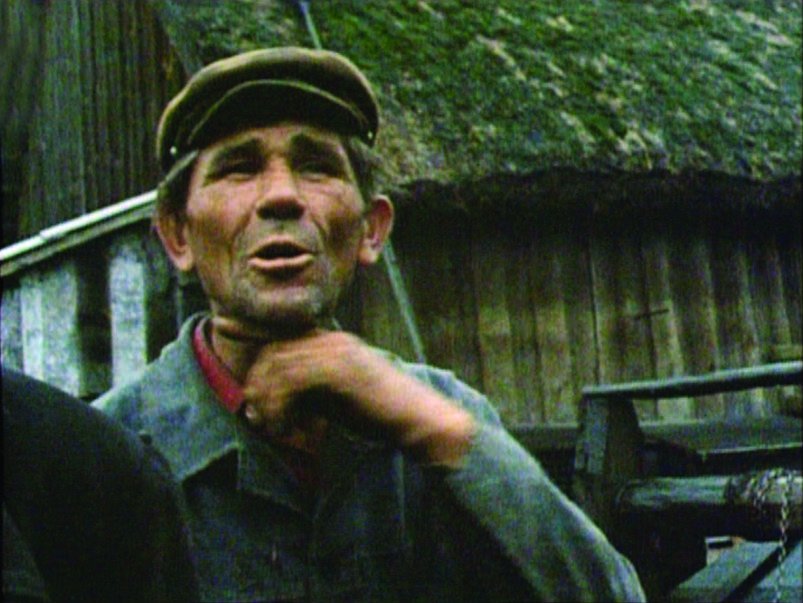

The film to which Dead Souls has most often been compared, Claude Lanzmann’s documentary Shoah, provides an illustrative comparison. The two films’ historical bases – the Holocaust and the Anti-Rightist Campaign – cannot be straightforwardly compared. But both films are about four feature films long; both record recollections of a national trauma, intersperse long takes of these recollections with wordless footage of what has become of the scene of the crime, and use neither archive footage nor extra-diegetic music. Both occasionally allow their directors into the frame. Both even have a haunting musical interlude: in Shoah, survivor Simon Srebnik sings an old song as he rows Lanzmann downriver, while Dead Souls features the aforementioned funeral, which features a full band as well as the melismatic wails of the deceased’s grief-stricken son.

But what doesn’t get discussed so much is how the two films differ. Most obviously, Dead Souls features only the survivors and their loved ones – no Chinese writers or foreign academics, no one who wasn’t directly affected by Jiabiangou. There is one interview with a former camp cadre, but he is not interrogated particularly, and comes across as almost as much of a victim as the actual victims. Even those that make it into the film number fewer than 20.

Shoah (1985)

Shoah, meanwhile, casts its net wide. It sometimes goes back and forth between its dozens of interviewees, from whom it extracts a variety of often contradictory testimonies. It even, in one covertly filmed scene, holds a specific person to account. On a cinematic level, its juxtapositions – its attempt at capturing the variety of experiences, motivations and rationalisations – ‘enliven’ the ten hours of testimony and make Shoah as much a study of the human condition as a painful exhumation of a specific historical period.

The lack of authority figures in Dead Souls is not, of course, Wang’s fault. He has always worked outside studio (and officially sanctioned) systems; the cost of this is not only funding but, presumably, certain practical restrictions on whom it would be prudent to approach for involvement. Wang is bullish when I ask him about his relationship with Chinese authorities, and whether they’ve ever given him any trouble: “No. Officially, my films aren’t circulated in China anyway. And I don’t think my films raise any particular problems or issues. They are not political films. Everybody who lives in society is [somehow] interconnected politically, but what I do is to record and show the lives of these people. That’s all I’m doing.”

Mrs Fang (2017)

Other than Mrs. Fang, which screened at this year’s Shanghai International Film Festival, Wang’s films have never been screened in his home country. But many Chinese have been aware of Wang Bing since illicit copies of West of the Tracks began circulating after the film’s suppression. “The pirated DVDs had sold a million copies by 2005,” Wang tells me. “That’s not an exaggerated figure.” Kerby adds that at one point there were five different pirate companies making their own versions of the film.

By political and therefore economic necessity, Wang’s working methods are simple: usually just he and one or two others following and filming people using basic camera and sound equipment, plus a small cadre of editors, translators and consultants in post-production (including his ex-wife, Zhu Zhu, who sifted through hundreds of hours of the Dead Souls footage). Given how resolutely uncommercial his films are, and how unforthcoming the Chinese government would be with funding, I wonder how he has continued to make films, with no other source of income, for all these years.

His longtime producer Kong Lihong tells me: “He doesn’t spend much in life. He’s frugal. Also, some of his films win prizes, [which] quite often come with money. For some films, producers manage to pay him a salary from the budget.”

She adds, “I work with him as producer, and have been since 2004, on very varied projects. And I never got paid, because we didn’t have enough budget. Only after 2014, maybe… because we’ve been getting more funded projects than before. I was not paid either.” She says this matter-of-factly, with no bitterness or regret. (Kerby chips in, laughing: “Wang never pays. Or only once.”)

’Til Madness Do Us Part (Feng ai, 2013)

Sometimes for Wang and his team, the financing experience is particularly bad – The Ditch being the prime example. Kong told me, “At the end, neither director nor producers got paid.” The team had worked on The Ditch from 2004 to 2010. “That happens quite often, actually.”

Wang found an unusual amount of creative freedom with Dead Souls. Coal Money (2009) had a time limit by which he abided, and ’Til Madness Do Us Part could not exceed four hours for festival circuit reasons. (When I ask him if he has any regrets about his films, he says he wishes he could have included more footage in those two.) But he came across no such constraints with Dead Souls.

“I had a thorough discussion with the producers, who all supported me,” he explains. “I basically had carte blanche… when I finished, I called them and said, ‘My film has reached such-and-such length,’ and they said, ‘OK, no problem, if you’re happy we’re happy.’ It was accepted by Cannes Film Festival, miraculously, so everything’s fine. I felt quite lucky about that.”

Dead Souls (2018)

But his prognosis for Chinese cinema is bleak. “In China, there’s a big film industry but no film culture. It doesn’t matter what kind of film you make – documentary, fiction, whatever. What’s important is that you have to show some truth. You can’t show a fake world in a fake way. In science fiction, everything is ‘fake’ but there’s a certain truth behind it. That’s the important thing.”

Kerby adds: “Most Chinese cinema in recent years has become more… unreal. Not in a surreal way, but in [terms of] a lack of truth. Realistic, but no kind of morality, no culture. Mainstream commercial crap. That’s what censors allow.”

Nonetheless, Wang – despite the austerity of his own documentaries – is a keen observer of arthouse cinema. He remains good friends with Pedro Costa, and praised a “very interesting film by Miguel Gomes” (he can’t remember which; I assume he means Arabian Nights). “Apichatpong [Weerasethakul] too. There’s really a lot of brilliant filmmakers around; these are just a few.” Veering off the beaten track, Wang continues: “In America in the 50s, there were some ‘paranoia’ films that were also very good. Experimental documentaries.” The last film that left an impression on him was one such work: Ben Maddow’s 1960 film The Savage Eye. Wang says he is also indebted to le cinema d’auteurs, and singles out Antonioni, Tarkovsky, Pasolini and John Ford.

The Ditch (Jiabiangou, 2010)

It’s often interesting to track the artistic development of these auteurs; Wang’s development is harder to trace. Has his methodology or approach to filmmaking changed over the last two decades?

“No,” he says flatly. “Technology and equipment change, but my understanding of cinema and my approach have never changed.”

Wang has been living in Paris for over a year (though he doesn’t yet speak English or French; Kong was interpreter for this interview). Would he ever make a film about somewhere that isn’t China? “I’m interested in maybe going to Africa to shoot,” he tells me. “There are a lot of Chinese people living and working there. I’m quite curious to know how they live, how they manage.”

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.