Ever since her debut with the 1994 graduation short film Isaac’s Dream (Le Songe d’Isaac), an exploration of dream and fantasy framed in a highly controlled aesthetic, Swiss filmmaker Ursula Meier has consistently developed her own particular filmmaking voice, notable for her rigorous eye and an appetite for questioning generic conventions and experimenting with visual and narrative styles.

Two more acclaimed shorts – Sleepless (Des Heures sans sommeil, 1998), portraying the subdued intensity of a brother and sister reunion through body language and flashbacks, and Table Manners (Tous à Table, 2001), which used verbal improvisation to dissolve the boundaries between fiction and observational documentary – were followed by two feature documentaries (Autour de Pinget, 2000, and Pas les flics, pas les noirs, pas les blancs, 2001) and the TV film Des Epaules solides (Broad Shoulders, 2002), part of the Arte series Masculin/Féminin. The offbeat family-drama features Home (2008) and Sister (2012), winner of the Berlinale’s Silver Bear Grand Jury Prize, sealed her reputation as one of a new generation of European arthouse cinema leading lights.

Ursula Meier

Encounters Short Film & Animation Festival’s 2015 focus on Ursula Meier includes the following events:

• Quiet Mujo in Short Film programme 1 – Turning Points, Wednesday 16 September at 10am and in Short Film Highlights, Saturday 19 September at 10am

• Music and Sound in the Filmmaking Process with Ursula Meier & John Parish (who composed the soundtracks to Sister and Kacey Mottet Klein, Birth of an Actor), Friday 18 September at 7.15pm

• Ursula Meier retrospective, Saturday 19 September at 4pm

• Sister, Saturday 19 September at 6.15 pm

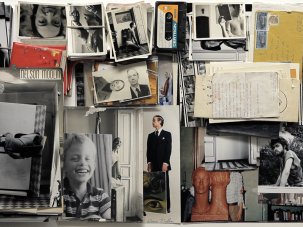

Since Sister, Meier – who also lectures at both Lausanne’s ECAL film school and La Fémis in Paris – has returned to the short form. In 2014 she made the 11-minute drama Quiet Mujo (2014) – part of the anthology film The Bridges of Sarajevo in which 13 European directors explore the theme of Sarajevo past and present. And this year she has completed the 14-minute documentary Kacey Mottet Klein, Birth of an Actor (2015), half lesson in cinema, half portrait of the eponymous young actor, which draws on his work in both of Meier’s two features to date.

As Meier heads to Bristol for a host of special screenings and appearances at this year’s Encounters Short Film and Animation Festival, I caught up with her to talk about short-form cinema, film collectives, festivals and the place in the industry of female filmmakers.

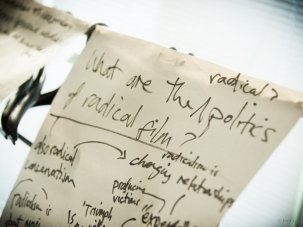

What’s the relevance of making short films for you?

I love short film. It’s one of the last places where a filmmaker can find freedom. These days production for auteur films has become a struggle: there’s a lot of pressure, it’s more and more difficult to take risks. But this is not case in short films, which I think should remain a laboratory.

At film school I tell my students: “Take risks, try things out. Even if you make mistakes, short films is the place to put yourself in danger, to gain experience because it will become more difficult when the budgets and the stakes are higher and one has to fight to protect one’s vision.”

Can you talk about what role short films had in your career?

My short film Tous à table was awarded the audience award, the critics’ award and the Prix Recherche (research prize) at the Clermont-Ferrand Short Film Festival in 2001, a combination of awards which rarely happens. I took a huge amount of risks with it; it’s a film I made for myself, to experiment with the actors, the script, the mise en scène. I needed it to do the opposite of what I had learnt at film school.

Isaac’s Dream (Le Songe d’Isaac, 1994)

And it is indeed the opposite of my first film at film school, Le Songe d’Isaac, which was very controlled. It’s a film I made in the most personal way, so much so that I didn’t even want to finish it! It was a producer who saw it, thought it was really good and encouraged me to finish it… Then it was selected by a lot of festivals and won a number of awards, something which really comforted and encouraged me to keep doing my work with a lot of honesty, to try things out.

Experimenting doesn’t necessarily mean going against the public and Tous à table, with its audience award, proves it.

It sounds like being selected in Clermont-Ferrand marked a turning point for you. Do film festivals still play an important role in launching a filmmaker’s career?

Absolutely! Clermont-Ferrand is a major festival and Tous à table’s selection there brought in the money to finish it. Afterwards the film had a very successful festival life – and I remember seeing others at the same time that came out of nowhere because Clermont had selected them. This is still the case today with the most important international short film festivals, regardless of the ever-growing online presence of short films.

I have Clermont-Ferrand in my heart because it was extremely important for me. Two of my short films, Des Heures sans sommeil and Tous à table, won awards in Clermont and it’s thanks to them that Arte gave me the opportunity to participate in one of the themed Arte Collections series created by Pierre Chevalier. They wanted to include a first-time feature filmmaker in each collection, and I was paired with established filmmakers such as Catherine Breillat and Mathieu Amalric. The result was my TV feature Des épaules solides.

Having served on a number of short-film festival juries, do you think the risk-taking potential of short filmmaking is still appreciated?

From what I can see, the difficulty I described of continuing to make personal, experimental films without alienating the audience seems to affect short filmmakers too. There are many films that are well made, well shot, well acted with a nice story but where something is lacking. Something strong, perhaps disturbing – something that, as a viewer, will put me in a pretty uncomfortable place.

Sleepless (Des Heures sans sommeil, 1998)

I’m talking about films which provoke me, question me, even ‘mistreat’ me as a human being. Well, there aren’t too many. Sometimes short films are a little bit too much ‘calling cards’ and this is a shame. Mainly when I’m on a film jury I ask to make sure there is an opportunity to talk about films, even of those films that we might not award but that have something that interests me. Having free reign to talk about cinema doesn’t happen that often these days!

What elements strike in you in a short film?

There aren’t any fixed criteria; it can depend on the context. When I teach in film school I try to put my taste aside to show or discuss someone’s talent even if it doesn’t reflect my taste. As a jury member, however, I’m going to defend what I consider good cinema. For example, there are films that trouble me; some films reveal an audacity which shouldn’t be ignored, even though they’re less ‘perfect’ than others.

Do you think those films have a very personal voice?

Exactly, and often, as a viewer, they put me in an uncomfortable position. This is something I would love to see more of. Often I find myself being in too comfortable a position so the film ends, it was well-made and had good intentions but… that’s about it!

There are short films that marked me for life, that I show to my students and tell them: “In only a few minutes, this is pure cinema!” I think about Scorsese’s The Big Shave (1967) – I show it to my students and say “This talks about so many things in only a few minutes”, or the English short doc Lift (2001), or La Peur, petit chasseur (2004), a single static shot short film which won in Clermont-Ferrand a few years ago. Some short films are real masterpieces. Lynne Ramsay’s shorts are another example. There are a number of short films which marked me as strongly as features.

Table Manners (Tous à Table, 2001)

I think the problem these days is that short films have become an industry, a market, so an instrument – student films included. Everything in these films is of a good standard and well made to pave the way for a feature, but a less well-made film where there’s something that makes me go ‘wow’ would express the filmmaker’s ‘feature potential’ even more. I really like short films made by filmmakers who have never made films before, they just go and do it and you see something striking because it’s not a film made with the intention of showing that he/she are a good filmmaker.

Can you say something about the context behind Quiet Mujo?

It’s part of The Bridges of Sarajevo, an anthology feature film. Thirteen European filmmakers including Jean-Luc Godard, Cristi Puiu and Teresa Villaverde were asked to make a short film about Sarajevo as part of the centenary of World War I.

At the start I thought I was going to make a documentary, then ended up making a fiction after asking myself lots of questions. I love commissions because they give me a framework to work within.

You’re part of the film collective Bande à Part. It’s an interesting and rather unusual dimension for a filmmaker to work within. How do you work together and what do you get out of it?

This seems to fascinate people in the film industry. When I talk to French producers, I’m often told that in France these days working like this would be unimaginable. Everything is too individualistic. Maybe it’s only because Switzerland is a very small country that this can work.

It’s a long-term friendship, we used to help on each other’s projects, give advice, exchange ideas, sit through one another’s editing sessions, and at some point we thought it could be a good idea to somehow ‘formalise’ our collaboration and work/friendship relationship through a production company.

Initially we were associated with two producers and then it became just the four of us: Lionel Baier, Jean-Stéphane Bron, Frédéric Mermoud and myself. It’s a brilliant collaboration, like having found a ‘family’, because we’re regularly in touch with one another, we discuss our projects, share one another’s successes, there’s a real collective spirit which is actually very rare these days when making a film is often something very solitary.

Each of us has an official producer in France, but then Bande à Part is the Swiss counterpart to that. What makes it even more interesting is that we are four very different filmmakers which means we don’t step on one another’s toes. It is very enriching.

Mujo Quiet (2014)

Is a collective something you would advise emerging filmmakers to explore?

Not necessarily. I still think that filmmaking remains a very solitary dimension. Of course there are some very strong artistic partnerships in place: I work regularly with Agnès Godard as my DP, for example. But beyond that there’s a strong feeling of solitude and I don’t believe in the collective dimension in the sense of ‘we’re doing everything together’.

With the four of us I think that it actually works because we have distinctive personalities, work on our projects on our own and the other three provide a constructive, supportive look – and because we’re of the same generation and have a common view on cinema. But it’s not about getting together and making a film together. I can assure you it’s very hard to find this sense of a strong, common and generous spirit while at the same time being able to follow one’s own individual filmmaking voice. But it all came naturally from our friendship, it wasn’t planned.

Finally, given the focus at this year’s Encounters on women in front of and behind the camera – what is your perspective on this issue?

I don’t think that cinema has a gender. There isn’t a female or a male kind of cinema; there’s just cinema.

It’s true, especially in Europe, there are more and more women directors, cinematographers, sound designers… But unfortunately in certain countries it’s still impossible for a woman to use a camera and make her own film. When it comes to big-budget films, whether in Europe or the US, it’s still really exceptional for a woman director to be in charge. And this in itself says a lot about the role of women in the film industry, which is actually not so different from their place in society at large.

Regarding stereotypes on screen, there would be so much to say…

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.