from our February 2014 issue

Credit: Corbis Images

How did you get started as an independent filmmaker and how did you come to make Night of the Living Dead [1968]?

Well, I went to Pittsburgh to go to college at Carnegie Mellon University and met some people. I‘d always loved movies – I was always a fan – but I never imagined I’d be able to work professionally in film; I thought you had to be born royalty or something… Carnegie Mellon had a wonderful theatre department but film studies was just watching movies, watching Battleship Potemkin and talking about it. There was no equipment, no practical hands-on learning experience. But there were film labs in cities the size of Pittsburgh because the news was [shot] on film at that point. There were three big film labs that processed 8mm, 16mm and 35mm and I used to just go and hang out, and that’s where I learned the basics; from these journeyman news guys and the editors who were cutting the newsreels.

Then one day me and a few friends went to an uncle of mine to try and raise $20,000 to buy a Bolex and a lighting package, and we set up a company to do commercials and industrial films, and over the next couple of years we became very successful at that. We were the only game in town that was doing commercials on film. We got more equipment and eventually we thought we had enough equipment to try to make a movie, a narrative film. So, that’s how it happened.

I understand Orson Welles and Howard Hawks were an influence on you. The Thing from Another World was a film you enjoyed…

Yeah, I enjoyed Thing from Another World, but Welles was more of an influence. When I see Night of the Living Dead though, all I can see still are the mistakes! Basic filmmaking 101: eye direction, screen direction and all of those things. I was clueless about all of that. It’s typical of a commercial director where you just focus on a shot at a time instead of, even in your head, storyboarding the whole action of the sequence.

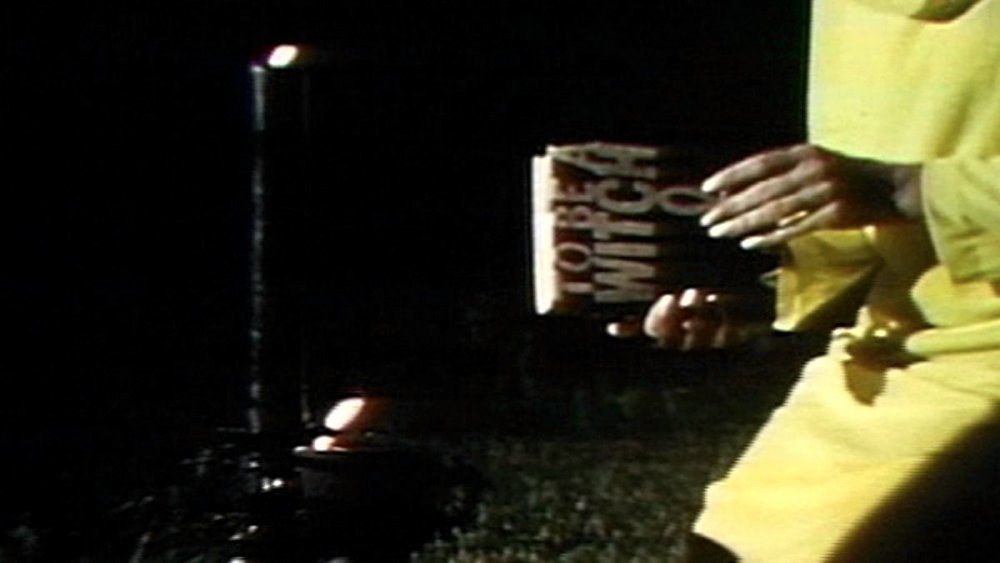

Hungry Wives (aka Season of the Witch, 1972)

But In those early films – I’m also thinking about Hungry Wives [AKA Season of the Witch, 1972], The Crazies [1973], Martin [1976] and Dawn of the Dead [1978] – there is a real ‘Romero style’ that emerges: a lot of cutting, carefully composed shots, depth of field, a focus on details and a lot of music. Was that a style you consciously developed?

It was, and I was better off that way. I used to cover my ass with cuts because if you covered everybody that was talking with single shots you could make the dialogue run any way you wanted it to run, whereas if you’ve got a master you’re stuck with what you’ve got. So that was my way of putting off decisions. And very often that would save the day. Having those options gave me the ability to develop that frenetic style.

It’s a sort of nervous energy that adds to the anxiety of the stories.

I hope so. I thought that it did. But then what happens is, as we started to make films with union crews and needed to compress shoot time, I had to develop more of a traditional way of doing it.

Yes, in the 1980s you developed a more conventional style.

This again was a defence mechanism. I needed to be able to make sure I got the information in a master and tried to choreograph and use camera movement instead of cuts. It was hard to come around to that. The first time I did it with any success was Bruiser [2000] maybe.

Creepshow (1982)

Not Creepshow [1982]? That is a bit more conventional in its style.

It is but we weren’t pressed financially or schedule-wise with Creepshow. So it still has the remnants of the earlier style, and of course the comic-book format enabled me to do different things. Panning from panel to panel… That was just fun!

It’s a fun movie. Going back to Night of the Living Dead: it’s a film that in many ways is the first truly modern horror film. It reflects so much of the unrest of the time – the 1968 student riots, the civil rights movement. How much of that was by design, and how much of that was subconscious or a happy accident?

A lot of that was by accident. The main thing people took from Night of the Living Dead was that it was a racial statement movie, and that was completely unintended. Completely. When John Russo and I collaborated on that script, in our minds, he was a white guy and when Duane [Jones] agreed to play the role we consciously didn’t change the script at all. We thought, we’ll be hip and not even notice that he was black.

Duane was very aware of it. He was really conscious of being a black guy in this role, and of course because he is black it takes on a completely different personality – a completely different texture and politics. We were a bit blind to it.

Night of the Living Dead (1968)

In fact, I’ve often thought we would have been better off to change the script and make race a point. There was a point could be made there. Here is a minority person faced with these redneck people. And that person might become paranoid and make the wrong decision. And he does, he makes the wrong decision, in the end.

Politics also comes into the film in other ways. The disintegration of society and societal norms…

And family. That’s really what we were most conscious of, instead of a racial theme.

That’s something that continues in your work. The Crazies has elements of a satire that looks forensically at how parts of society might behave under extreme circumstances. You see how the politicians relate to the army and how the army deals with the local doctor and the police, and how the locals respond to the baton of authority…

Yeah, I hope it does. That’s a theme I keep returning to because I think that is one of the big problems that we have. When I first did Night of the Living Dead, I didn’t call them zombies… Zombies weren’t dead before. I thought, “These people are going to be dead and they’re not going to be able to dig their way out of graves because they are too weak.” My zombies have never eaten brains! I don’t know where that came from. The Return of the Living Dead [1985] maybe. Because they could never crack open a skull.

It’s en masse that they become a threat.

Yeah exactly, but they’re dead, right? So I thought that was a new creature. I never called them zombies. But what I wanted was something amazing, something earth-shaking, an incredible disaster out there – and our people in the house are still concerned with their own little agendas instead of rationally dealing with the problem. Because it’s relatively escapable, but they seal their own doom by being too wrapped up in their own concerns. That’s the big theme I see all over society. People focused on their own thing.

The Crazies (1974)

It’s like in the US; the politics now are just ridiculous. We’re all shooting at each other. That’s one of my big concerns about society in general and I guess that’s why it always creeps in. Often a lot of these things are unconscious until it’s finally on the page and you’re out there staging it, shooting it and really thinking about it. It comes out in the process.

There is a sort of naturalism to the performances in many of your films. I’m thinking about films like Hungry Wives and The Crazies, where the performances give the films a realism that horror hadn’t had before. Details too: in The Crazies, the extras in the white radiation suits. In most films they would be background characters, but you make them human. You show them getting frightened. And there is that great shot where one steals a fishing rod. That sort of naturalistic detail seems to me to be a real Romero trait.

It’s hard for me to talk about that specifically because so much of that is spontaneous. I’m just always looking for things, you know? Like, this guy is going to walk through here, he might think, “Oh, look at those fishing rods. Why don’t I just grab ’em?” Or the scenes of them going through [dead people’s] pockets. Maybe that recalls the Holocaust… I wasn’t thinking so much about that at that moment, its just these guys would probably be doing that kind of thing. So, I always throw that in.

It’s just like with the zombies. In Zack Snyder’s remake of Dawn of the Dead [2004], they’re all dressed the same and are in running shoes. First of all, they shouldn’t be running! They’re all in blue jeans and running shoes and that’s it. But I try to make them nuns or…

Hare Krishnas.

Yeah! Do something with wardrobe to give it a little bit more flavour. Why not, you know?

Martin (1976)

If we could talk about Martin. It’s filmed in Pittsburgh on a low budget and with a small crew. I understand it is a favourite of yours.

It is my favourite film of mine…

It feels like a personal film when you watch it.

Yeah. I would say Knightriders [1981] is maybe a bit more personal in that it is a little more about me – my own defiance. I won’t say I’m uncompromising but I won’t compromise just for the hell of it [laughs].

Knightriders is about doing something outside of the normal system and having integrity and believing in what you’re doing. Which I guess is an analogy for you as an independent filmmaker?

That’s really what I meant, but you said it much better. So, in that sense I don’t think Martin was as much of a personal film.

But I was able to make every shot that I wanted to make. We had a very small crew; the actors were carrying the lights. Everybody was just there to make the movie. And I got every shot I wanted. It’s the only time that’s ever happened. The sequence where they’re on the telephones – when he interrupts the lovers… That whole sequence, I couldn’t have done that without that number of shots. I needed those shots to tell that story visually.

Martin (1976)

That scene is a perfect example of the Romero fast-cutting style.

Yes, it’s a good example of that. I needed the shots and I had this dedicated crew that was all about making this film. It was great. That’s really why I like that film so much.

And do you feel most comfortable working on your home turf with a small crew who you really know well?

Pretty much, yeah. I’ve sort of found that again in Toronto. Again, a team of people who I’ve worked with as long as I’ve been there. It’s great, I have a new family! Pittsburgh, for a while, became a production centre. There was one $400 million year. Hollywood was bringing productions in there. Films like The Silence of the Lambs and Innocent Blood. So my guys, the guys I worked with, were able to have careers and live at home. But then it dried up and a lot of my friends left.

And you always resisted the move to Hollywood…

Oh I did, yeah. I really didn’t want to do that. I’ve never shot a film there.

Land of the Dead (2005)

Even Land of the Dead [2005], which is a studio picture, was shot up in Toronto…

Yeah… it was actually a pick-up. It wasn’t a Universal production. We made the deal with an independent producer called Mark Canton and he sold it to Universal. But our original deal was with him.

Did they get involved after the production?

They were starting to be involved during production, but they never made a script change or anything like that. They did insist on cast.

I heard they didn’t want a black lead? I guess they had commercial reasons for that…

Yeah, they did. Actually it was Canton first who said that and Universal backed him up. They claim you can’t sell a black lead – unless it’s Denzel [Washington] – in Europe…

In Europe? Oh, so it’s our fault after all…

That’s what they think.

I guess they have the figures to back it up…

Statistics lie! My reaction was to make Big Daddy, the lead zombie, black. And he is the hero.

Staying with Land of the Dead, it takes on new meaning after the financial crash, what with Dennis Hopper’s evil capitalist trying to take the money and run. The anger of the zombies is perhaps analogous to the anger of the people.

We saw the film projected recently and I had those thoughts. The politics of that film are in your face: [adopting a sarcastic tone] “We don’t negotiate with terrorists!”

Dawn of the Dead (1978)

Credit: Kobal Collection

Dawn of the Dead is also a comment on the state of the nation. How did the idea to critique consumerism come about?

I resisted for a long time, because people were talking about Night of the Living Dead as if it was important, and I thought, “I can’t do another one until I have an idea that is not necessarily important but something to satirise at least.” Socially I knew the people who were developing this shopping mall – literally the first indoor shopping mall in Pennsylvania. So I went out to visit it before it was even opened and I saw the trucks bringing in everything that you could ever possibly want… And I got the idea right then.

I started to noodle on a script and, serendipitously, Dario Argento found me through my agent and called. He had just shown Night of the Living Dead out in a field somewhere to a big audience and fell in love with it. He called and said, “You must make another one.” So, he brought me to Rome and I wrote the script. We’ve been friends since then.

What was your budget on Dawn?

It was around a million and a half [dollars], I think. Richard Rubinstein, the other producer, found $700,000, from US sources. Dario’s was the first money in but we needed to match it. It really was a big production and it was the first time that we went with Screen Actors Guild actors, so their wage demands and working demands shot the budget way up. And there were a lot of people to feed. And we had to pay for the use of the mall…

Dario made it clear right away, he said, “Look, I won’t touch your version; you make the film you want to make. But I need to be able to change it for non-English-language European audiences.

He did his own edit for Europe…

Yeah, but he was very upfront about it. And I loved his stuff too, so I said, “Sure.” So that’s the deal we made. The band Goblin too, he said, “You can use this, don’t use it or use some of it.” I wound up using some of it.

Dawn of the Dead (1978)

I like the contrast of music. Is the other music in the film library music?

Library, yeah. Dario’s personality is more like “Rah!”, whereas I’m like, “Hey!” [laughs]. I think that is reflected in that score. He takes it so seriously, everything has got to be serious. He cut all the humour out of the original version and we had trouble with censors in the UK. They wanted to cut two-and-a-half to three minutes out of his version. But when they saw the US version they got a lot more lenient because the humour takes the edge off some of the gore.

Dawn of the Dead had an immediate knock-on effect. Suddenly there were these Italian zombie films coming out from the likes of Lucio Fulci, and also in America later on there were The Return of the Living Dead films. How did you feel about this unofficial response?

I don’t know. I found it sort of funny and typical. If anybody hits a home run with anything there are going to be ten or more imitations.

Did Dawn’s success open doorways to bigger budgets? Did studios come knocking?

Studios have always knocked [laughs], but I’ve never seen a script through my agent that I’d want to spend my time on. And I was always able to generate my own stuff. I just never saw the need.

I did two films for Orion, The Dark Half [1991] and Monkey Shines [1988]; Creepshow wound up being distributed by Warners, but they bought it from United Film, the guys who initially distributed Dawn in the US. United gave us a three-picture deal after Dawn and that was Knightriders, Creepshow and Day of the Dead [1985]. And they gave us carte blanche to make the films we wanted. We had creative control and that’s why those films have the kind of energy that they have. But Warner Bros picked up Creepshow at Cannes.

The Dark Half (1991)

Creepshow was quite a commercial success…

It was. My only number one movie! Number one on the Variety charts. The only time that’s ever happened.

And it was a collaboration with Stephen King. You had a few other collaborations. King gives a great cameo performance in Knightriders. And I believe you had a few other things in the pipeline.

We had a great time working together. He wrote the stories for Creepshow II [1987]. I wrote the screenplay and it was directed by Michael Gornick. And then we worked together on the screenplay for Pet Sematary [1989] but I got tied up doing the goddamn re-shoots for Monkey Shines, and they had to start shooting, so they went with Mary Lambert [as director]. I also worked with Stephen closely on The Stand, when it was a screenplay. Originally we wanted to do it for film because Stephen thought he’d have to water it down too much for TV. But then all those deals all blew apart and I did Dark Half.

I went to Orion for that because they had just distributed Monkey Shines. I wrote the screenplay for Monkey Shines, which was adapted from a novel. But they blew it. They were the worst – a terrible studio. They made all the wrong decisions. They kept films they should have thrown in the garbage and they hated films that made a lot of money. They didn’t like Dances with Wolves… They didn’t like The Silence of the Lambs. They thought it was “garbage”. And that’s a quote!

Monkey Shines (1988)

If we could just talk about Day of the Dead. That was scaled back from how you had originally envisaged it. You settled for a lower budget so you could put in more gore. Gore tends to be used in exploitation films for commercial ends, but you’re potentially making your film less commercially viable by having that level of splatter…

In that sense, yeah. I mean today – give me a break. [AMC series] The Walking Dead is damn near as bloody as Day. Well, maybe not quite!

Day is pretty full on.

Yeah, Day is pretty rough [laughs].

Where did it come from? That desire to have so much gore, even if it meant your film might not reach as many people as it would without it?

I thought that I needed it. It may have been misguided but I felt that it was a slap in the face. It was a reminder… Like, “Hey, maybe take this a bit more seriously.” And I was thinking consciously of Altman’s MASH. You know where you’re laughing your ass off for 90 minutes, and then you go into the operating theatre and this gore hits you so hard. I was hoping for that kind of an effect. I’m not trying to be extreme with it. Also it’s a bit of a signature.

Day of the Dead (1985)

Tom Savini’s effects are spectacularly good as well. Especially by the time you get to Day of the Dead.

Oh yeah. He’s really hit his stride with Day.

Day is a very bleak film – all these people in this underground space not getting on. It’s about the complete breakdown of communication…

That was the whole thing. It’s like a pressure cooker – literally, with a lid on it. That was the intention. The idea that the army might have potentially caused the phenomenon, that lingers too. I mean, we don’t know. It could be voodoo, or God’s punishment… I never wanted it to be a returning satellite [laughs].

The story about that is, we had a couple of other explanations in the original film [Night of the Living Dead] and we just cut them because the distributor wanted the film to run no longer than 90 minutes. We needed to cut six minutes, so we cut out news casts because there were enough of those. And that’s where the other explanations were offered. I felt the one scene in Washington, with the army and the scientists talking, was enough. It’s left uncertain; one guy keeps saying, “We’re not sure about that.” But everyone interprets the film as a returning Venus probe causing the dead to come back to life.

Survival of the Dead (2009)

Since Land of the Dead, you’ve gone back to smaller productions…

Yeah, I was happy to get back to the roots. I had problems with Land. I loved Dennis [Hopper] but I was very uncomfortable to see that one of the biggest line-items on the budget was his expensive cigars [laughs]. The catering… everything goes up when you have Simon Baker, John Leguizamo… when you have these stars.

You’ve never really used stars…

No, I think the anonymity helps, because you never know what’s going to happen to whom. But working on a smaller scale means more creative freedom. The same company financed Diary of the Dead [2007] and Survival of the Dead [2009] and they gave us final cut, so it was really back to the old days.

And is that more enjoyable than working on a big scale?

Much more. You don’t have to write a memo… [On a large production] if you see a sunset and you’d like to shoot it, you’ve got to email first to get permission…

Diary of the Dead (2007)

Credit: Kobal Collection

Diary has some of your purest horror sequences. You adopted a quasi-realist, camcorder style. Did you want to do something a bit more set-piece based?

Yeah, basically. It was hard to do that. We never really achieved it. I mean, if you could see the editing sessions… I wanted it to be absolutely pure, with no visible cuts. But I wound up in some sequences having two cameras running so the cuts were sort of explained, and I put in this device that she, [the lead character] Debra, is editing the footage that the guy originally shot. We had to do that because we just couldn’t pull it off in single takes… We wound up having to do that, but it gave us the opportunity to put in all the news footage and the Getty images and all the other stuff that really adds to the film. It’s about citizen journalism…

Zombies have surged in popularity again: the Dawn of the Dead remake and The Walking Dead. How do you feel about where it is now?

Well, it’s just got terribly crowded, hasn’t it? Now you can’t sell a zombie film unless you promise to spend a lot of money. I think it belongs on a smaller, more intimate scale. I certainly don’t think you need World War Z at all. I know Max Brooks, who wrote the book, didn’t like it at all. I didn’t like it when I first saw it.

Do you feel a degree of ownership? Do you care about how zombies are used in popular culture?

I don’t think so. I just used to be the only guy and it was my little private cache. I could bring the zombies out whenever I wanted to and do something with them that maybe had something to say. And then all of a sudden it just became another creature.

World War Z (2013)

And basically it’s a first-person shooter now… I think the popularity came from video games, not from films because up until Zombieland [2009] there was no film that grossed more than 100 million bucks. The remake of Dawn did $75 million. Hollywood isn’t going to be particularly interested at that level. And then all of a sudden, I think it was Brad Pitt who went after Z, and he somehow convinced the studio to spend an exorbitant amount – unnecessarily.

And the zombies aren’t loaded with the same sort of political meaning.

Nothing. I mean I don’t see anything. It’s a disaster movie. They were even carefully avoiding the word. You had to extrapolate it from Z. People who didn’t know the book might figure World War Z means the final world war. They’ve finally got to the letter Z! Even in the advertising, they never used the world zombies; they never showed a shot that looked like zombies. They look like army ants, you know?

Are you keen to keep up to date and watch a new zombie film if there is a big one out?

No… I sort of had to watch that one. They invited me to watch it. They wanted me to say something nice, I think [laughs].

Lastly, I’d like to go back to Knightriders, as it’s an overlooked film. It’s quite uncommercial in some ways: 140 minutes is long for a genre film…

Yeah, it is, but luckily the distributor loved it. He didn’t know how to distribute it, but this guy Salah Hassanein, he was just like one of the old-school moguls. He was the guy who originally distributed Dawn and gave us this three-picture deal. He was a flamboyant Egyptian guy, a great guy and he loved the movie, but he didn’t have the power or the money to distribute it effectively.

Knightriders (1981)

Did it receive a limited release, then?

Oh yeah. And also, whenever a Romero movie comes out people want it to be Dawn of the Dead, you know? Even Day of the Dead, the reception was very cool initially.

I watched the original Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel review of Day. They’re so down on it. Nowadays, that’s a film cherished by so many people…

I know. It’s too bad they don’t show up when it matters. Unfortunately, it takes a while. In fact, on this trip, just yesterday, I met the first journalist I’ve ever met who said, “Survival of the Dead is my favourite of all six.” Finally someone has come around to liking Survival of the Dead. And I think that’ll probably keep happening, like with Day of the Dead…

I’ve tried to make the zombie films different from each other. I was hoping there would be another one. I wanted to do a noir, black and white. But it was not to be because Survival just tanked. Day of the Dead remains my favourite zombie film of mine. So much of it is again in the process – remembering everyone being there to make that film, everyone there to work with one purpose. And no bad apples – a wonderful time was had by all. And we are all still friends. Good memories.

-

Sight & Sound: the February 2014 issue

Joel and Ethan Coen on Inside Llewyn Davis, Steve McQueen on 12 Years a Slave, Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street, Altman’s The Long...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.