Web exclusive

The Stalls of Barchester

No English writer unleashed more savage ghosts than M.R. James, and no screen director ever realised them more successfully than Lawrence Gordon Clark, whose cluster of short films made annually for the BBC in the 1970s, and known under the title of A Ghost Story for Christmas, are the most cherished examples of the genre that British television has ever offered. These “cobwebby Christmas presents” work so well not because of a strict regurgitation of the stories they are adapted from, but because of a remarkable dedication to the principles that make M.R. James’s stories so effective. These films revel in their period settings, be they cloistered academia or stark seaside guest houses, in the playful language of lonely intellectual men, and in blurry English landscapes. But most of all they work so well because their moments of fright are not only genuinely savage and fearsome, but brief.

James may not have been a master of characterisation, narrative or pace, but his ability to turn a story on a short row of words was masterful, and always the aim was simply to frighten. Famously in O Whistle and I’ll Come to You My Lad (1904), the reticent storyteller relating the disturbing events concerning Professor Parkins says that when pressed to describe the figure that appeared in his room one night he remembers “a horrible, an intensely horrible, face of crumpled linen.” The moment reaches beyond our mere intellect and runs a long cold finger inside of us at the place where our earliest fears reside. For of course that inexplicable linen devil reminds us of the childhood fright we got from someone scaring us by throwing a white sheet over themselves and pretending to be a ghost.

One of Clark’s most effective displays of the Jamesian method of frightening an audience comes in The Stalls of Barchester, when in the portentous atmosphere of the Cathedral Close, in the dead of night, a ghostly elongated hand of unnatural colour and motion reaches over and touches a shoulder. In part that deathly hand is such an effective scare not just because of the old shock tactic of an unexpected hand falling on our shoulder, but because of the sheer crudeness of the image. In its putrid colours and with its talon-like nails, it is an intrusion from the childhood imagination, derived from the picture book and the penny dreadful as much as from a dark corner of the nursery, and crucially, it is an intrusion into the respectable adult world. Given that that world in the story is also a world of learning and sanctity makes us uneasy: it should be is a far cry from childish things. We can never fully escape our childhood images of fear because they got to us before rationality did, and both James and Clark are devilishly aware of this.

Television is curiously well-suited to the ghost story. Unlike theatre and cinema, it is is an intimate medium which delivers its spooks into one’s own home. A Ghost Story for Christmas was one of countless examples of the success of a regime of creative freedom the BBC was enjoying in the late 1960s and through the 70s, a period writer Arthur Hopcraft described as “a time when television wasn’t trying to imitate other mediums. It was a medium all on its own and it understood that, perfectly poised between theatre and film.”

It was this thriving drama department at Television Centre that Lawrence Gordon Clark was trying to engineer a route into in 1971. “I came into drama from documentaries. The best way to do it in my opinion,” Clark remembers. “You did have a good deal of freedom back then to bend the rules a little, so I’d started incorporating little drama inserts into documentaries, reconstructions and such like. I was itching to move into drama and knew I had exactly the source material I wanted. I’d discovered M.R. James at boarding school and loved him. So I met with Paul Fox, who was at the time Controller of BBC1. I brought a copy of M.R. James’s Ghost Stories with me, with a bookmark stuck in The Stalls of Barchester Cathedral. The fact that period drama always has been very popular at the BBC probably helped. The reply I got was simply ‘Okay, how much money do you need?’ It was an extraordinary time. He allowed me a budget of £9,000 to make the film, so off I went!”

Jonathan Miller’s Whistle and I’ll Come to You

Another factor that possibly helped Fox make up his mind was the critical success that Jonathan Miller’s imagining of O, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad had been for BBC1 three years earlier. Miller, having made two astounding films for television, had deserted it for the National Theatre, never to return. “I thought Whistle and I’ll Come to You [as the television film was named] was excellent, and probably would have offered that story to Paul first if Jonathan Miller hadn’t already done it, and done it so well,” Clark adds. “The other M.R. James adaptation that had been done of course was Night of the Demon, which I really liked, but felt they got the monster wrong. I was coming from a love of the stories as works of literature and was keen for this to be about the power of suggestion, and being very sparing with what was eventually revealed.”

To keep expenses to a minimum, Clark adapted the story of an ambitious holy man murdering his predecessor himself. While The Stalls of Barchester Cathedral may be the simplest of James’s stories to turn into a workable screenplay – given its linear structure, few locations and detective-story pace – Clark’s screenplay is really quite beautiful. His sense of humour in the early scenes at Dr. Haynes’s frustration with the longevity of current Archdeacon Dr. Pulteney is particularly commendable, partly because it plays so enjoyably and also because it is written with total confidence that it will not sabotage the dark moments that lie ahead. And indeed it doesn’t. The scares, when they come, are scripted and directed with a remarkably steady hand, Clark utilising the power of words, of images, and also of silence and darkness.

Some of the script’s most chilling moments are in the dialogue, whether it be the repeated anguish of Archdeacon Haynes’s diary entry “I must be firm” or in perhaps the most uneasy moment in the whole drama, when, after being startled by the carving in the cathedral seemingly becoming a surface of thick black fur, Haynes asks for the history of the Cathedral’s odd decoration from his sinister, goblin-faced Verger. The evening’s service is over, and the cathedral is now very empty as the two men explore the designs, in the Verger’s words: “nasty little things I’d say. No place in the Lord’s house in my opinion.”

Holding up his candle he points out casually that “on the south side there’s the angels and the blessed an’ that,” and then, with his tone only a touch more wistful, continues: “an’ over here… is the damned. Everlastingly burning Sir. As is their lot.” In the silence that follows Haynes looks up at the wall, and a ghost walks over the viewer’s grave as he senses the chill of dread the god-fearing Haynes must be feeling, knowing that with the blood of his predecessor on his hands, the terrifying scene is one the Archdeacon will one day face himself.

For the lead role of Archdeacon Haynes Clark cast the trusty Robert Hardy, himself a fan of ghost stories and a firm believer in the supernatural. Clive Swift took on the role of Dr. Black. A noted expert and lecturer on the performance of Shakespearean verse, Swift is naturally blessed with a marvellously jovial storyteller’s voice that takes the dialogue on a ride over boundless cadences and sings when reading out Haynes’s cryptic diary entries.

The Stalls of Barchester is a little miracle of television, a labour of love made on a tiny budget with skill and care. The ecclesiastical setting and music (not to mention a flurry of snow in a woodland scene) make it easily the most Christmassy of the films, but despite that the story is in no doubt that even in the season of goodwill, there will be no rest for the wicked.

A Warning to the Curious

The jewel in the advent crown for Christmas 1972 was the most impressionistic of Clark’s films, A Warning to the Curious. Cameraman John McGlashan captures an extraordinary atmosphere of a seaside town in winter, blurry and sterile; indeed the film looks as aged and mysterious as the weathered crown that the plot centres around. Although James stated that the fictional village of Seaburg in his original story was based on Aldeburgh on the Suffolk coast, the production chose the sorrowful landscapes of the North Norfolk coastline as the location, and shot in a bright but cold autumn, again shooting for ten days and coming in on budget.

It is the most poetic of the films, revelling in its awkward unsettling dialogue and obsessed by its environment more than any of the other instalments. The working-class Paxton, recently unemployed and chasing a rainbow in the form of an Anglo-Saxon crown, is the most forlorn of all the protagonists Clark depicts. Upon his arrival at the guest house, the boot boy looks scornfully at him after seeing his battered shoes. The only people capable of striking up a normal conversation with him are those who are not from the area, and of those, even the Vicar, having been here twenty years, is weary and embittered. Clark swiftly creates a picture of a conspiratorial community with no mercy for those who try to plunder it, however innocently.

When the moments of fear come, they are particularly fiendish: the overnight excavation at the spot where the crown is buried is brilliantly eerie, but the most explicit moment of shock, in which the ghost of William Ager returns to snatch back the crown, works because of Clark’s mastery of minimalism: after we are plunged into darkness, a torch beam roams around the room accompanied by frightening sound effects, finally settling on a figure lying face down on the floor in a dirty black overcoat. As the beam fixes on it, the head turns towards us just enough for us to feel sure we saw a deathly white face and empty black eye sockets. But before we can see any more everything goes dark again. A Leatherface four years before Tobe Hooper created him, the Ager ghost is possibly television’s most petrifying phantom since it is not only, from what we can see, horrific, but also unstoppable and murderous.

Necessary liberties had been taken with the text of A Warning to the Curious to turn it into not only a brooding thriller, but one where the menace is as much environmental as supernatural, but the result more than justified this. “That one was very well received again, but what happened was the series had now drawn attention to itself” recalls Clark. “By the following year this was a traditional part of Christmas television, and so predictably, the BBC woke up to this. They were taken over by the drama department, and Rosemary Hill was assigned to produce them. This did mean I didn’t have total freedom anymore, but it also meant the films got a little more money! They also became tighter, because they were now scripted by well established writers and then put before a script editor.”

Lost Hearts

Lost Hearts, broadcast in Christmas 1973, saw some significant changes to the series, and also saw it losing its rightful time slot of the approach to midnight on Christmas Eve. Immediately the effect of the administrative developments is apparent: the film looks splendid, beautifully costumed and with some astoundingly crafted photography. It may lack slightly the personal touch of the first two films, but Lost Hearts is itself a markedly different story for M.R. James and one that finds its horrors in different moods and manners to the more typical tales.

In Lost Hearts we have not one but two ghosts, and they are children. They are mischievous, frightening in appearance and vengeful, but they are not evil. They are there to warn the eleven year old Stephen of the murderous magus Mr Abney, his geriatric and seemingly benign cousin, and after amusing themselves by waiting until the last minute to actually intervene, save Stephen and murder Abney before tripping away into the hereafter.

Robin Chapman’s script pairs down James’s rather cluttered story into a straightforward, pacey tale, but surprises us by opting to make the ghosts a very visible presence throughout the story. Every entry in the series conforms to some degree to Clark’s, and James’s, method, of only allowing one shock reveal of the horror it promises, and whilst Lost Hearts does indeed only once allow itself a moment of stark terror, namely when the ghost children reveal the nightmarish sight of their torn chests, hearts long since stolen, it is peculiar in showing its ghosts throughout not from a distance or in shadow but almost in close up.

“I was never sure if we got Lost Hearts right. I worried that we saw too much of the ghosts, when I was well aware of the power of suggestion,” Clark says. Lost Hearts does survive this uncharacteristic explicitness though because the real horror it is preparing the viewer for is the inevitably unmasking of Mr Abney.

Recent commentators have seen Lost Hearts as at heart a story of child abuse disguised in a thin cloak of magic, but the disturbing premise surely hints at a much broader concept, and that which any child fears long before it even understands the concept of abuse, simply that of a kindly parental figure actually meaning them harm. The image of the witch remains one of a child’s most potent fears because it is a corruption of the mother figure, just as Mr Abney desecrates reassuring childhood notions of relatives and old people as figures of generosity and compassion. How can we survive in this world if those in control of us and and who dwarf us should mean us harm? Where else can we go for protection?

Lost Hearts sees the beginnings of Lawrence Gordon Clark’s fascination with sunlight, exemplified by a stunning shot of sunbeams reflected in a river. Elsewhere the land is romantically sinister, in an establishing shot of nightfall in the grounds of Abney’s house shot through a spider’s web, or picturesque in the joyous depiction of Stephen’s birthday as he flies his kite on a hillside to the tune of Vaughan Williams’s ‘My Bonny Boy’. No other film in the series, not even A Warning to the Curious, celebrates the English landscape so candidly.

The Treasure of Abbot Thomas

John Bowen, one of the most bewitching storytellers television could ever boast, was entrusted with the 1974 offering, based on one of James’s most fiendish and fun creations, The Treasure of Abbot Thomas. This time major changes took place to James’s story, bringing in a typically mischievous Bowen subplot involving fake mediums and gullible old ladies, introducing a protégé for the inquisitive academic, and changing the location to England.

While James’s doomed heroes are frequently accused of displaying a fatal intellectual arrogance, this story is actually the only example of Clark depicting this trait in his films, unless one counts the deluded beliefs of Abney in Lost Hearts. And even here, despite the Reverend Justin Somerton’s gentle intellectual bullying of the assorted guests at afternoon tea early in the film, it is in fact the young Lord Dattering who appears to be the one more likely to stumble blindly into the lair of a ghost, displaying as he does a combination of precociousness and academic snobbery.

But things are never just in James’s world, and it is the charming and tranquil Somerton whose fate is sealed when he begins hunting for the mythical treasure of “not the good Abbot Thomas”, a treasure that the Abbot has set a guardian over and deliberately left tantalising clues to its location. In fact in Bowen’s screenplay even more than in the original story the suggestion is that the Abbot is deliberately feeding the pair clues to ensure they do walk into his trap. He is not trying to keep treasure hunters away, he is trying to lure them in.

The Treasure of Abbot Thomas is a treasure hunt, but also a treasure trail. As well as the thrill of the chase, the script’s other great success is in its lead character Somerton (Michael Bryant) being one of the most engaging and smart heroes of the series. The location filming is once again glorious, much of it filmed in autumn evenings which, in one of the final lines, we are reminded “come upon us quickly”. Geoffrey Burgon also contributes an astounding soundtrack, a unique fusion of monastic wailing from two counter-tenors, sparse percussion banging and chiming here and there, and occasional chaotic organ notes which create a truly unholy atmosphere.

Initially his admiring protege, Lord Dattering becomes more and more waspish to the increasingly haunted Somerton, until finally in Somerton’s lodgings, where appropriately the broken pieces of a bust of a human brain lie scattered across the floor, he is downright callous towards him. Somerton’s intellectual arrogance and composure at the start collapse under the might of weightless forces, and in the final moments Peter, seeming to have won the respect of his mother at last and grown up in her eyes, walks off arm in arm with her and her companion leaving a muted Somerton alone in his bathchair to await the Abbot’s final visitation.

The Ash Tree

Christmas 1975 gave us The Ash Tree, a fiery tale played out on a bigger scale than the previous films. This time the adaptation came from David Rudkin, a writer with a strong sense of the past and of the mystic (most notably in Penda’s Fen), and also one adept at jolting his audience. His script is perhaps a little portentous and lacks the spark of many of the other adaptations, but it does benefit from a barbaric performance from Barbara Ewing, whose curse cry of “mine shall inherit” haunts the mind long after the closing credits.

The Ash Tree’s ghosts take the form of monstrous spiders, and to achieve the climactic sequence of their infestation of the tree, visual effects designer John Friedlander built a squad of disturbing little beasts which even in close up look effectively nauseating. Clark again remains uncertain as to the success of the tale, saying “again I think we maybe dwelt too long on those. They did actually look very good and I hope we did get that across, but the longer something is actually on the screen the less effective it is.”

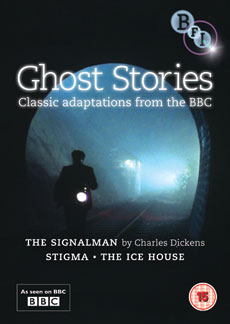

The following year saw the most famous episode of the series, The Signalman. This was the first film not to be derived from an M.R. James story, its source instead being a short story by Dickens first published in Christmas 1866. “What happened was that I started planning that year’s film, and was all set to do another M.R. James story. We were intending to do Number Thirteen. And I just didn’t think it was going to work. I reckoned you needed to shoot it in Scandinavia, you needed those forests and that environment. So we went back to the drawing board and chose The Signalman, which I have very vivid memories of. Andrew Davies of course wasn’t famous then like he is now – in fact this was one of the first adaptations he did – but his script was absolutely wonderful.”

The film is essentially a two-hander, and is the most intense acting piece of the series. Thankfully Clark’s casting was impeccable, the role of the signalman going to Denholm Elliott, at this time reaching his peak as one of the best character actors of his generation. As the other man with no name, the personable traveller, Clark cast Bernard Lloyd.

“Weren’t they both magnificent?” exclaims Clark. “Denholm in that, to me, was like a tightly coiled spring. You could actually see the tension in the character’s face every second. The signalman was clearly only ever a short step away from cracking up and going over the edge into insanity. And Bernard was perfect, a lovely, lovely performance, and the two of them together just gelled.”

The Signalman

Filming took place in October 1976 on a stretch of the Severn Valley Railway just outside Kidderminster which itself is rumoured to have a few ghost stories attached to it. The signalbox interiors were shot at the signalbox at Highley Station, while the “unnatural valley” can be found at Bircham Coppice Cutting, a stretch of line into a tunnel that borders the aptly named ‘Devil’s Spittleful’. Clark has vivid memories of the shoot:

“Believe it or not, where we shot The Signalman we were in a valley which was slap bang beside a school and a housing estate. So there we were trying to get this shot in what was pretty terrible weather for much of the time, and Denholm and Bernard had quite a hard time of it, children throwing things and disrupting the shoot. Looking at it you’d think it was shot in the middle of nowhere though. Also The Signalman was the one time we didn’t get everything finished on time. We had very heavy fog that did for us, and I had to ask for more time.”

The Signalman is probably the most successful of the whole series, its intimate and intense narrative the core of what is an immensely atmospheric and unpretentious piece of drama. The performances are pitch perfect, the ghost is startling and fleeting, and Clark and cameraman David Whitson give us the most foreboding glimpses of haunted England of the whole series. The valley where the story unfolds is excellently dim and gloomy, daylight scuttling away the closer we move towards the endless blackness of the tunnel mouth. The traveller’s brisk night-time walks back to his lodgings are even more impressive, silvery blue fog daubing the moor as the inn sign creaks like a witch hanging from a gallows.

The Signalman, while being one of the most succinct examples of the English ghost story, can also been seen as part of the Gothic movement because like the Gothic novelists, Dickens saw a dark underbelly to the white heat of technology, sensing the echo of the old in the shock of the new.

But like the Gothic novelists revealing paranoias about 19th century society, its values and its relentless advances, from Frankenstein the evil scientist early in the century, through Jekyll and Hyde and ending with Dracula as the ultimate evil aristocrat (and foreigner) at the end, Dickens’s Victorian scare story warns that however fast society moves, the past is always just one step behind and the unknown always one step ahead.

The Signalman

The Signalman, sadly, was the last of the literary adaptations, and after one more entry, the less successful modern-day Stigma by Clive Exton, Clark left the BBC. Those looking for something closer to the style of Clark’s films from other hands are advised to seek out Granada’s Shades of Darkness anthology from 1983 instead, and in particular The Intercessor, the only other really comparable film in terms of its atmosphere of spiritual decay and repressed unease.

Clark continued his association with the supernatural at ITV, who in the years that followed gave him far more opportunities to explore his talents as a director than the BBC did. Casting the Runes in 1979 was a disappointment, although the serial Chimera in 1991 was a ratings success and was at best a pretty smartly made fusion of conspiracy thriller and monster fantasy. The anthology series Chiller, which he produced and co-directed for YTV in 1995, was patchy, although it did kick-off strongly with the breathless epic Prophecy, adapted from Peter James’s novel.

His career highlights elsewhere include HTV’s Jamaica Inn (1983), the emotionally charged Sun Child (1988) starring Twiggy and James Fox, and his most prestigious production, the charming Romance on the Orient Express, in 1985. He has never made a film for the cinema, but that should not be seen necessarily as a missed opportunity.

Clark understood television like a fair number of other sensitive and passionate directors who developed at the BBC in that era understood it. They achieved great things they couldn’t have elsewhere. Of those who did defect to the cinema, not all proved it was a wise move. Clark’s skill was in modesty, in a love not for sweeping landscapes but in the sun reflected in a pond, not in large casts but in two men talking over a mug of tea in a signal box. And most of all, in a flash of terror half seen and then seen no more until we try to go to sleep that night.

Lawrence Gordon Clark’s M.R. James adaptations are now available to view in a series of BFI DVDs.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.