This is an extended version of an interview originally published in our July 2012 issue

Holiday (1957)

In the rich and occasionally revered world of archive (aka assemblage / bricolage / compilation / détournement / found-footage / mash-up / remix) filmmaking, appropriation rather than invitation tends to be the order of the day. No doubt many of its high-flyers – Ken Burns, Bill Morrison, Andrei Ujica or Maciej Drygas – have upstanding relationships with their institutional sources of footage; some, like Adam Curtis at the BBC, are lucky enough to work for the organisation whose stockrooms they scavenge; while Austria has such a fecund community of cut-up artists (Martin Arnold, Gustav Deutsch, Peter Tscherkassky), you wonder if an archive pass is part of the country’s welfare accord.

Still, the task of acquiring extant imagery, particularly from pop culture’s corporate guardians and often for irreverent or critical reinterpretation, is onerous enough to make ‘pirates’ of the likes of Craig Baldwin, Mark Rappaport, Thom Andersen and Christian Marclay. And that’s to say nothing of the mass of digitally enabled amateur remixers whose newfound creativity is under siege from conservative judges and biddable politicians worldwide.

That said, there’s a sense that – again, partly spurred by new digital possibilities – film archives themselves are becoming more proactive in bringing their wares to the public, seeking to promote public access to as well as preservation of their endowments. Just within the UK, the BFI and 11 regional archives last year launched Search Your Film Archives, a consolidated, partly viewable online catalogue of their respective holdings. This year the North West Film Archive released a ‘Manchester Time Machine’ iPhone app, putting 80 years of geolocated city street footage in your pocket. The BBC’s Creative Archive experiment (2005-06) may have returned to its subterranean lair, but the Beeb (along with the BFI) has again partnered with the Arts Council on The Space, a collaborative, experimental digital channel for arts and cultural organisations to interact with audiences.

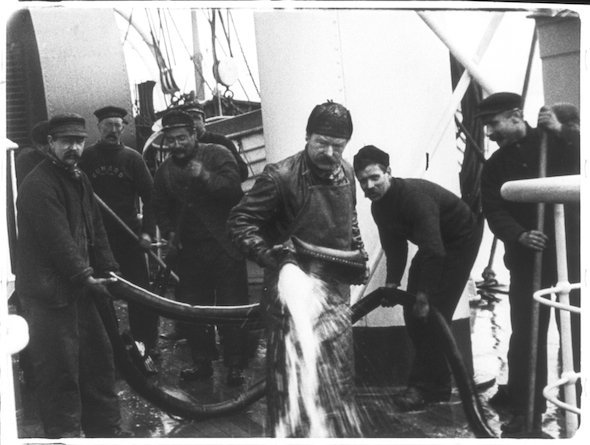

Mitchell and Kenyon 235 S S Skirmisher at Liverpool (1901)

There’s also been a trend of inviting filmmakers to rework archive collections, perhaps inspired by the success of Terence Davies’ Liverpool-history homage Of Time and the City (itself made with a grant from the since-reorganised local screen agency and UK Film Council). The production agency Forma corralled a host of (North East) regional and national bodies for Bill Morrison’s The Miners’ Hymns in 2010, the same year the BFI dispatched the hauntology musician Mordant Music into its basement to mash up the Central Office of Information collection as MisinforMation. And since last year’s institutional reorganisations, the BFI has joined the BBC as a potential one-stop shop for production funds and archive access, a scenario already benefiting both Julien Temple (currently making the archive London paean BABYLON/DON) and Ken Loach (just beginning the archive doc Spirit of ’45, an ‘oral history’ about the birth of our welfare state).

First, though, the versatile Penny Woolcock (The Principles of Lust, The Death of Klinghoffer) joins the ranks with From the Sea to the Land Beyond, a found-footage tapestry of British coastal life commissioned by Sheffield Doc/Fest and the transmedia agency Crossover, and stitched together (with editor Alex Fry) from four key BFI collections: Mitchell and Kenyon, Topical Budget newsreels, British Transport Films and the COI. When I went to see them midway through a five-week edit, they were working to a scratch track of old recordings by – who else? – British Sea Power, with a new soundtrack pending before the film’s unveiling on 13 June at Doc/Fest’s opening night, and at the BFI Southbank two days later.

Mitchell and Kenyon 235 S S Skirmisher at Liverpool (1901)

What was the attraction of diving into the past? “The idea of doing something where nobody would want to kill me,” Woolcock laughs, citing opposition to her 2009 Birmingham gang musical 1 Day from the West Midlands police. (At Doc/Fest she’ll also be showing a follow-up, One Mile Away.) She was relishing the novelty of unmetered access to the old movies, too (“It’s usually so expensive using archive footage”), and of being able to experiment with “purely visual”, voiceover-free storytelling, away from TV commissioning editors who mandate that a documentary tell its audience “what’s going to happen, what just happened, what is happening…”

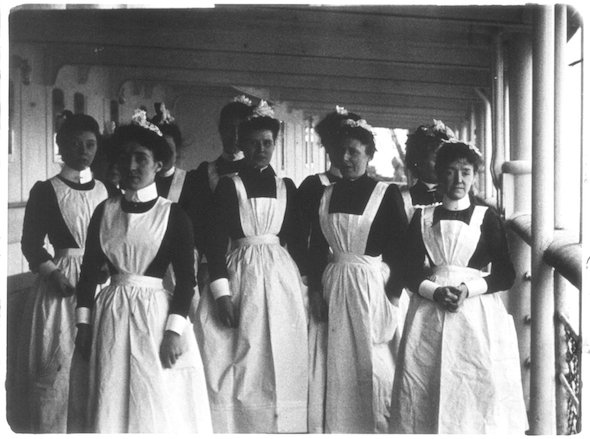

To judge from a rough cut, the film’s subject is indeed the tides of time, the montage finding poetic links and changes as it sketches a social history of 20th-century Britain through documentary of coastal labour and recreation. Workers leaving a factory stare with eager, healthy naivety at the novel camera, wondering what it can do for them (and movingly meeting their gaze with ours across the eras); Edwardians conduct bizarre aquatic contests in hat and tails (shades of Humphrey Jennings’ Spare Time), for amusement and then, perhaps, for war training. Industry grows, and in tandem the filmmaking becomes more confident and voluptuous – there’s a stirring dolly shot up and over a huge ship in the making.

Mitchell and Kenyon 235 S S Skirmisher at Liverpool (1901)

As Woolcock observes, most of these movies were shot as state propaganda, idealised imagery (though she’s counted the handiwork of Jennings and Peter Greenaway, Vaughan Williams and Michael Nyman, Dylan Thomas and Laurie Lee among her raw materials); but they also express an idealism, asserting the lives of ordinary citizens rather than the rich and mighty. Then there’s a tipping point – or perhaps a series. Female revellers become beauty contestants become pictures in the paper; women disappear from the workplace; industry disappears and people grow fat. Docklands become real estate, stockbrokers invade the fish market; Woolcock even bluntly rhymes an early-century Yorkshire cliff egg-gatherer with a 1980s jewelled egg tempting the new consumer class.

And, of course, film turns to video. For someone who hasn’t dwelled in the archives before and says she didn’t look to any prior found-footage filmmaking templates, Woolcock seems to have slipped easily into the conditional-perfect hauntological mode: “We didn’t want to do a nostalgia thing, but it’s hard not to – it all gets so shit.”

Aquatic Frolics Topical Budget 777

It’s not just Woolcock and Fry who get to delve into this stuff. From the Sea to the Land Beyond will also be online at The Space, along with some 350 minute-long clips from the same archives, dotted around a map of the UK; you can view them, arrange up to four on a virtual ‘postcard’, give each a different British Sea Power soundtrack and send them off with a note to your friends, ‘friends’ and followers. The project has been curated by Crossover’s Mark Atkin, who agrees this is just a first lick of the kind of interactivity that film archives are looking for. “People are warming to a sense of what’s possible,” he says. “There’s a hell of a lot of future in the past.”