Web exclusive

Bruce Conner’s Crossroads (1976)

Call it what you will: recycled film, archival appropriation, remix, found footage. While some practitioners consider it subversive and even revolutionary, and avant-gardists have adopted it as standard procedure, the practice of using pre-existing moving images in new works is actually deeply traditional, dating back to primitive cinema. As Arthur Edwin Krows points out in Motion Pictures – Not For Theatres, his anecdote-filled and sadly unfinished series on nontheatrical film, many early makers had few scruples about cutting footage created by others into their own work as if they had shot it themselves. Frequent extralegal borrowing often burdens students of early film, as it may often be difficult to determine the exact continuity of certain works, not to mention the provenance of appropriated shots. That said, the problem seems quaint when compared to today’s volume of uncredited appropriation enabled by digital technology.

In the highly contiguous realms of avant-garde cinema and film as art, the history and aesthetics of recycled film have been widely explored, and vectors have been drawn linking such figures as Joseph Cornell, Bruce Conner, Craig Baldwin and Gustav Deutsch. Many of these makers have spoken about their work, and the links between the works from which they appropriate material to the new films they make are overt, if not fully glossed or footnoted. We know much less about compilation documentaries, especially those produced in the last fifty-odd years, when sources of archival footage began to proliferate; studies of how they use pre-existing footage are sporadic and generally do not specify sources. And finally, we know the least about commercial and sponsored work made as part of the efflorescence of found-image-making that began in the late 1970s and continues today.

Avoiding the standard discussion of canonical figures associated with the cinema of appropriation, I’m instead going to offer a bit of history and try to trace key points in the last 35 years of moving-image recycling. In an attempt to redraft the trajectory as it’s commonly understood, I’ll focus on the populist, even the commercial, over the self-consciously artistic. (And given my coordinates, I’ll mostly be writing about US production.) Word to cinema-studies scholars looking for a thesis topic: the history of the found-footage movement (if ever such a group existed even in fancy) that treats artwork in parallel and intersection with commercial and television production is long overdue.

Credit: Prelinger Archives

We can credit found-footage film-maker, cultural theorist, microexhibitor and teacher Craig Baldwin with the apt formulation that found-footage film-making has a great deal in common with folk art – that in fact it is indeed one of the folk arts, now frequently accompanied with a kind of digital veneer. One might conclude from this idea that recycled cinema is in essence an informal, amateur-based practice that retreats from self-promotion. And yet some of the major nodal events in recycled cinema were the release of mainstream, highly-touted films.

While a few lonely artists like Cornell collected and recycled film in their work, prior to the 1970s most archival footage appeared in old-school historical documentaries like David Wolper’s Biography series and the long-running CBS series The Twentieth Century with Walter Cronkite. Using mainly footage licensed from the five major newsreel libraries and occasionally government-produced footage, these series focused on war, celebrities and disasters. Stentorian narration and predictable music accompanied clips that were assembled to tell a story derived from a pre-written script. Just like TV docs today, right? Well, one big difference: there was almost no representation of daily life or history as experienced by ordinary people, and the focus was on ‘official’ source materials – footage infused with the implicit ‘authenticity’ of the Big Five newsreels or the US government.

By the 1970s an increasing number of makers contracted an early version of archive fever and became fascinated with the unrealised potential of archival materials. At the same time, a heavily marketed nostalgia craze (remember Happy Days, Sha Na Na and The Sting?) opened the distribution doors for potentially more adventurous films set in the past, but not of the past. In particular, three films were, I think, tremendously influential: Howard Smith’s Gizmo! (1977), Philippe Mora’s Brother Can You Spare a Dime (1975) and Atomic Cafe (Kevin Rafferty, Pierce Rafferty and Jayne Loader, which was begun in 1977 and released in 1982).

Gizmo! presented footage of unusual and outsider inventions, oddities and stunts. Oddities were newsreel staples from early on and were frequently incorporated into derivative works such as Robert Youngson’s shorts and the SEE series sold for home exhibition through Castle Films. Gizmo! wasn’t simply a string of odd scenes; it infused a post-1960s editorial sensibility into archive footage that had entertained boomers’ parents, and mainstreamed footage of failed flying machines into a cultural meme. But Brother Can You Spare a Dime – a follow-up to Mora’s controversial Swastika (1973), a non-narrated compilation of everyday life in the Third Reich and first film to use Eva Braun’s colour home movies – looked quite different.

Beginning with a close-up of a pre-teenage boy’s face as he hyperventilates and then exhales the names of the 48 US states in a single breath, Brother is a visual romp through the Great Depression in America as presented in Hollywood feature films and experienced by the public. It’s filled with the kind of associative, non-literal editing that later became a staple of music videos and commercials, but at the time of its release seemed almost sacrilegious when applied to ‘authentic’ historical materials. Lacking narration and even a sense of narrative hierarchy, Brother splits into distinct sequences within which anything might and did happen. A few months before the Rafferty brothers and then-collaborator Stewart Crone drove a van to Washington to explore the wonders of the US National Archives and see what they might find to make a film, Kevin Rafferty described Brother to me in great detail, and it now seems clear that Brother heavily influenced the editing of Atomic Cafe.

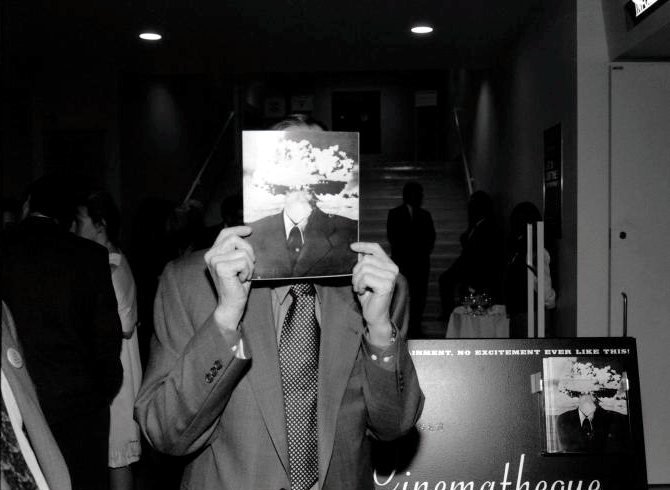

Atomic Cafe (1982)

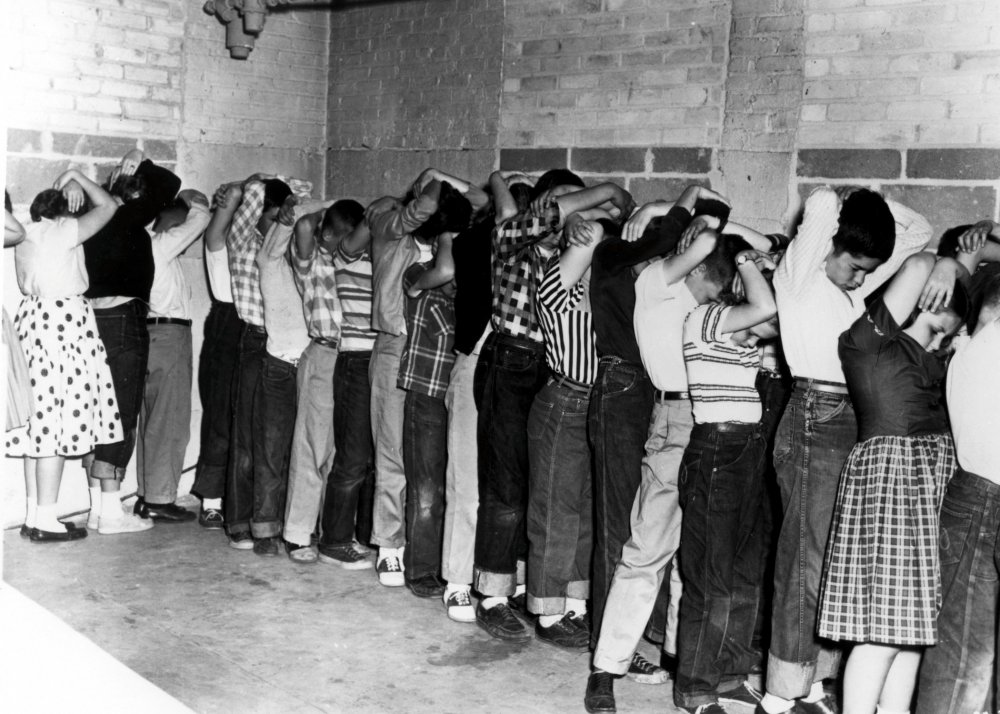

Atomic Cafe took five years to make, which seems long, but much of that time was spent researching images and sound that no one had bothered to see or hear since originally produced. Collaborator and lead researcher Pierce Rafferty looked at every Universal Newsreel in the National Archives and pried loose thousands of reels from military and government collections. The result was a truly postmodern film that mixed official and nonofficial documents, black-and-white and colour, literal and figurative imagery, actual historical events and material produced to persuade. Released at a time when the worldwide nuclear-disarmament movement was at one of its peaks, the film played throughout the world, propagating not only an anti-nuke message but strong implicit encouragement that archival film-making no longer needed to be tied to conventional narrative structures or character-driven stories. Unfortunately, in the big business that documentary film and TV has become, ‘storytelling’ and character has triumphed over innovation.

Atomic Cafe’s release came at a perfect time for makers infatuated with archives. The early 1980s saw a great opening up of distribution outlets as cable television and home-video businesses proliferated, both in urgent need of inexpensive airtime. Scores of new outlets seeking cheap air followed the paths well-trodden by countless other parsimonious producers and began to make heavy use of archival materials. MTV used first Universal Newsreels and later footage from every source imaginable for its innovative on-air promotion pieces. The music-video industry – and artists like Robert Longo and Ken Ross – used archival material as both backdrop and foreground. made music videos from archival material. TV commercial producers, ever in search of visual novelty, latched onto this trend. Perhaps most important as far as the long-term history of documentary is concerned, we saw the emergence of films (like Atomic Café or Lance Bird and Tom Johnson’s 1984 The World of Tomorrow) whose narrative was derived from the archival footage itself, rather than the footage being subsumed to a prewritten script or storyline.

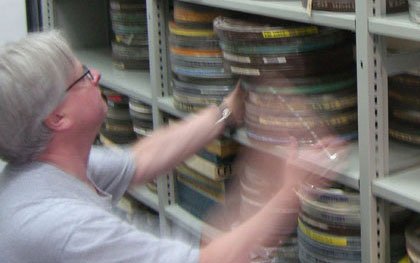

Rick Prelinger in the archive

As a collector of ephemeral (advertising, educational, industrial and amateur) films and commercial supplier of stock footage since the end of 1983, I saw the mainstreaming of archival material firsthand. While ephemeral films contained countless fascinating cultural and social evidence, their emergence (as clips) in more commercial media preceded their widespread adoption by artists. So far as I know, no one has yet researched or written the history of the commercial use of stock footage in the boiling media landscape of the 1980s and 1990s. While Mark Pellington has become a well-known movie director, his early work in the MTV on-air promo department isn’t known now, despite the fact that the editors of Natural Born Killers (to which we supplied a few clips) stated that the latter film’s omniverous, speed-stoked style was directly derived from Pellington’s work. Many fascinating aesthetic tendrils remain unexplored, too, such as the story of how archival footage changed from black-and-white to colour, a development for which we (as well as Petrified Films, our companion stock library, started by Pierce Rafferty and Margaret Crimmins) can take at least partial credit.

But by the late 1980s and early 90s, independent, avant-garde and activist media-makers latched onto archives, and as even a casual visit to YouTube or archive.org shows, they’re refusing to let history go. Formalised and formulaic uses of material gave way in the 1990s to a more collage-oriented aesthetic, and the proliferation and inexpensiveness of digital technology abetted the sampling movement. What I find most interesting about recycled media-making today is that while it has a firm home in the established art and media worlds, it has actually followed what happened in music and migrated into amateur, vernacular practice. Whether you identify as radical or traditional, producer or consumer, everyone and everybody remixes media, and in fact distinctions between producer and consumer are blurring so quickly as to become meaningless. As remixing becomes the folk practice that Craig Baldwin envisioned in the 1990s, remixing-as-art will give way to recycling-as-craft, hopefully birthing millions of new authors in the process.

If, however, remix, appropriation and recycling lose their adventurous and insurgent character and become simply style, as I’m afraid has already occurred, it will count for much less. Styles come and go, and when style is stale it takes much more than longing for cheap airtime and the efforts of amateur millions to bring it back. I hope that no cure is found for archive fever and that makers in new and emerging media (especially games and simulations) continue to find new ways to come to terms with the ever-fascinating, enigmatic and problematic contents of archives.

Credit: Prelinger Archives