Franchises, for good or ill, define the popular English-language cinema in the present century. Those who bemoan this fact (and I count myself occasionally among their number) will say that by thinking in terms of franchise, filmmakers are robbing cinema of one of its greatest assets, its concision and compression, and that the increasing reliance on building ‘worlds’ rather than freestanding movies that require no brand devotion or foreknowledge from a viewer has lured the cinema closer to the serial storytelling of television – and indeed it is hard to imagine the ultra-ambitious planned city project of the Marvel Comics Universe without the example of prestige TV.

Mission: Impossible Fallout is on wide UK cinema release.

Those who want to play devil’s advocate to this view (and I occasionally find myself doing this as well) may reply that there are no hard and fast rules in art and that any idea of cinema that can’t accommodate Step Ups (2006-) and Final Destinations (2000-11) and Resident Evils (2002-) needs to be rethought. And anyways the movies were doing the serial form long before TV and, come to think of it, doesn’t Tom Cruise hauling ass across the rooftops of London in Mission: Impossible – Fallout, the sixth entry in that series, put you in mind at least a little bit of Musidora sur les toits de Paris in Louis Feuillade’s Les Vampires (1915-16), among the first of the mighty film franchises?

The Mission: Impossible films, strong contenders for the most consistently cinematic franchise of the last quarter-century, took their basic elements from the cathode-ray tube, stripping for parts an old Paramount TV property starring Peter Graves that had run for seven seasons on CBS from 1966 to 1973, revived to little notice in the late 80s. Among the key elements retained was the concept of an Impossible Missions Force, or IMF, a covert intelligence task force taking jobs that no other agency could handle, briefed on each via communiqués that provide the films with their recognisable catchphrases: “Your mission, should you choose to accept it…” and so on.

Because the franchise remains so alive and kicking, it can be a little shocking to remember that the first Mission: Impossible film, released in May 1996, is old enough to have existed at a hand-holding distance from the New American Cinema of the late 1960s and 70s – to put it another way, we are as far from its release today as ’96 was from The Conversation and Chinatown and The Parallax View in 1974.

Mission: Impossible (1996)

This sense of proximity is underlined by the presence of the surveillance society-obsessed Brian De Palma as the film’s director, and through the contributions of Jon Voight as the heavy and Robert Towne as co-screenwriter – Towne also has a solo credit on the first sequel. With its insider double-crosses and don’t-believe-everything-you-see deceits, it’s a film that feels palpably connected to the loosely defined paranoid thriller cycle of an earlier time – the Towne-scripted Chinatown or De Palma’s Blow Out (1981).

With one foot in Nixon-era ‘trust no one’ cinema, De Palma’s Mission: Impossible took a giant stride forward with the other, indicating the future of the espionage movie after the end of the great political drama of the latter half of the 20th century, the stand-off between Nato and Warsaw Pact nations that ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union. Rather than operatives of a rival superpower, Cruise’s IMF agent Ethan Hunt has mercenaries and madmen for his opponents, a host of anarchists, nihilists and accelerationists – for the final triumph of the Pax Americana isn’t all it’s been cracked up to be.

While the IMF of the TV series divided time between domestic and international jobs, it is a globetrotting organisation in the films, the first of which begins with an extraction job from a party in the American embassy in Prague, a city that had been under communist rule only a few years before. Along with an attraction to exotic ports of call and the occasional fancy-dress event – rare excursions into opulence in these otherwise intensely goal-oriented films – De Palma’s Mission: Impossible introduces other key elements which will recur in the sequels.

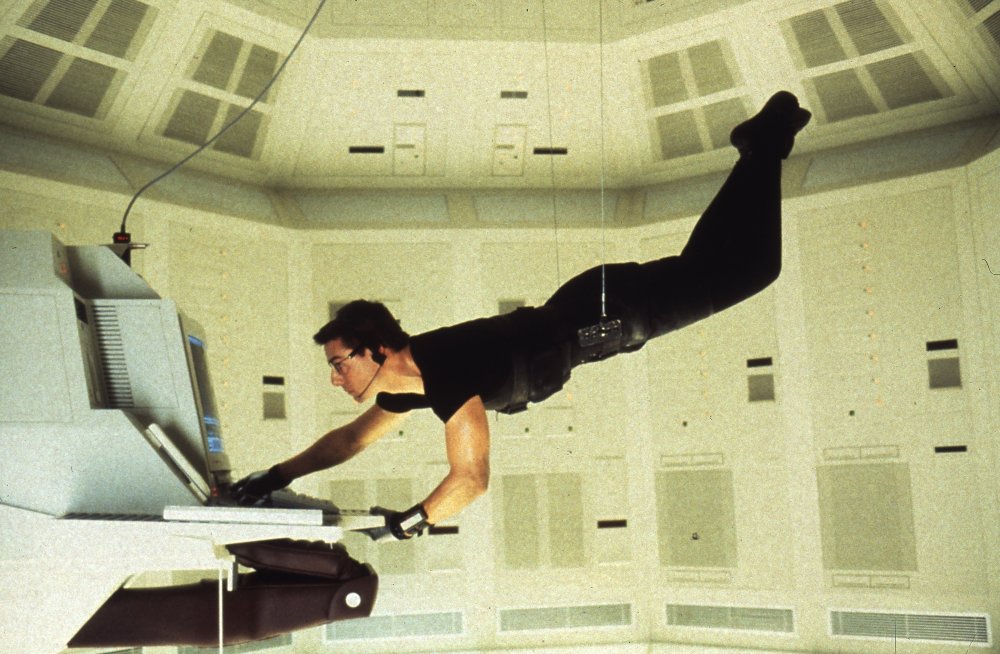

The one piece of spy tech that appears in every movie, the ultra-realistic latex masks that allow IMF agents (and their enemies) to slip into others’ identities, first appears with the introduction of Cruise as Hunt, ripping one aside to reveal his still startlingy boyish face. Its gangbusters set piece, which has Hunt and his team infiltrating the CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, to make off with a valuable file, provided the film its defining image – Cruise, suspended in mid-air by a wire harness, performing a balletic dance of supreme balance and self-control caught in full-body long shot.

Mission: Impossible (1996)

It also created a precedent for follow-ups, invariably containing a ‘heist’-style sequence in which Hunt and his cohort must break into a seemingly impregnable location in order to nab a human target or information: a skydive into a Sydney skyscraper in Mission: Impossible 2 (2000), a break-in at the Vatican in Mission: Impossible III (2006), a Kremlin caper in Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol (2011), a lung-bursting submersion in an underwater facility in Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation (2015), and a club gate-crashing that begins with a freefall over Paris in Fallout.

Hunt’s team changes from mission to mission – the exception is Ving Rhames’s heavyweight hacker Luther Stickell, though he is limited to a pre-credit roll cameo in Ghost Protocol – and series producer Cruise’s behind-the-camera personnel switch-outs as well. De Palma was involved with only the first Mission: Impossible, and until Fallout, the second film in the franchise written and directed by Christopher McQuarrie, Cruise has operated a revolving door policy for a host of directors du jour: John Woo (2), J.J. Abrams (III), and Brad Bird (Ghost Protocol).

Mission: Impossible II (2000)

This system has allowed filmmakers with strong grips to leave their fingerprints on a Mission: Impossible – imagine, by comparison, if Eon Productions had hired Mike Hodges, John McTiernan and Tsui Hark to make James Bond films through the years, and helped to ward off stagnation.

Each film is of a piece with the series, but with its own personality. Limp Bizkit feeding Lalo Schifrin’s theme song through nu metal crunch badly dates 2, but it’s baroque and barmy and sexy and silly, with enough Christian kitsch and gun fu to leave no doubt that this is a John Woo picture. Bird, reteaming with the first film’s legendary editor Paul Hirsch, creates some of the most elegant sequences in the series, and has the best gear, too – that rolling mirage screen! – as befits a whiz-kid retro futurist.

While the director position has traditionally provided the variable factor in sequels, Cruise himself is the constant, and altogether the franchise operates as a case study in the idea of the actor as auteur. The appeal of the character of Bond has proved to be larger than any single actor, while it is difficult to imagine an Ethan Hunt other than Tom Cruise.

Mission: Impossible III (2006)

In every Mission: Impossible movie Cruise is producer and star, having initiated the creation of the first through the auspices of Cruise/Wagner Productions, founded with CAA agent Paula Wagner and signed to a production deal through Paramount during a period of sustained popular success that seemed it would last forever. It didn’t, but the Mission: Impossible films have proved Tom Cruise-proof – that is to say, resistant to the waxing and waning of his box-office appeal as affected by his use of Scientologist wage-slaves or, far more uncharitably received, his outbursts of sofa-hopping enthusiasm – while paradoxically being built entirely around Cruise, catering to his skill set and the peculiarities of his persona.

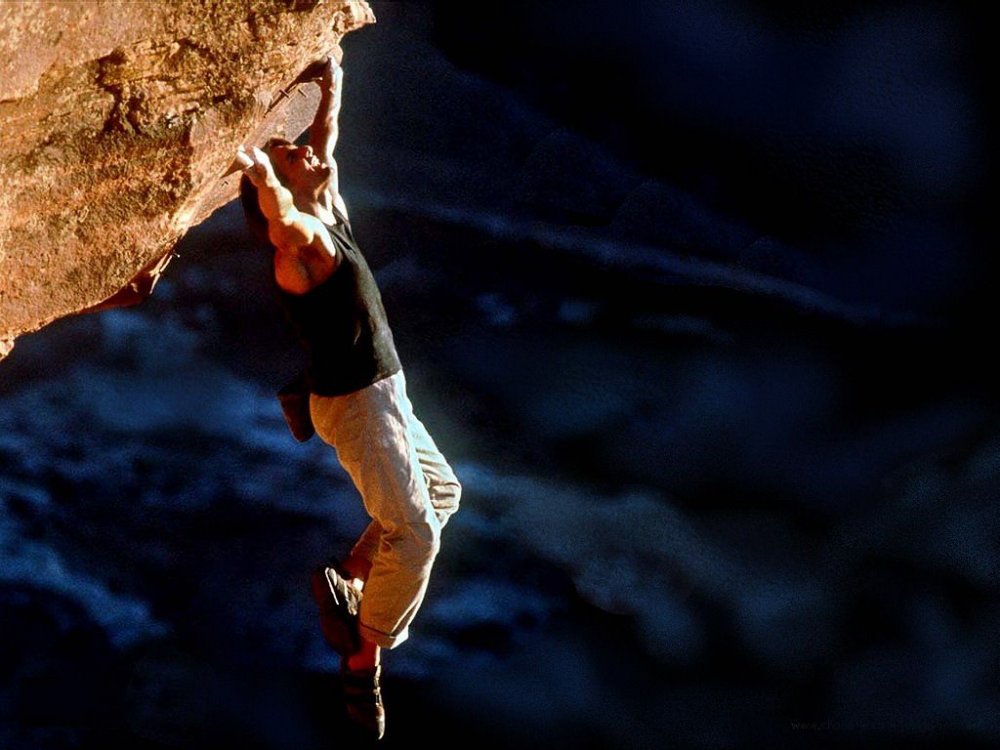

This is most striking in the degree to which Cruise, able to circumnavigate insurance worries in his producer role, has used the Mission: Impossible movies to accommodate his stuntman-star ambitions. In his boisterous athleticism, Cruise is the nearest thing American pictures have today to the bounding Douglas Fairbanks, but where Fairbanks worked to make his feats of derring-do seem effortless, Cruise’s Hunt is forever just managing to hang on by his fingertips, clinging from precipice after precipice.

Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol (2011)

Each instalment of the series offers new opportunities for the actor to perform feats of unusual speed, coordination and strength, invariably preceded by a promotional ballyhoo campaign confirming that, yes, really, that is Tom Cruise you’re seeing free-climbing on craggy red rock in Dead Horse Point, Utah, in Mission: Impossible 2 or clinging to the side of a cargo plane during takeoff in Rogue Nation – albeit heavily trussed with cables later to be removed via CGI.

In Fallout, the now 56-year-old actor takes a Halo (high altitude, low opening) parachute jump, drives a motorcycle against traffic around the Arc de Triomphe, dangles from a helicopter and, as if to do one better than the Jackie Chan of Police Story 3: Supercop (1992), finally climbs in and pilots the damn thing. All of this, of course, allows Cruise to burnish his legend as a fearless screen immortal, but it also indicates a belief in the indexicality of the moving image apparatus that is rather movingly old-fashioned in a moment where conventional wisdom has it that everything can be faked in post without any noticeable loss of veracity.

All of this is what we have come to anticipate of these films, but what is unexpected is that Fallout is also an affecting piece of work, and not only because one can sense the passage of time in the way Cruise has begun finally to show his age – if not in the spry stunts, then in the stubbled cheeks that have begun a slow descent into jowliness.

Simon Pegg, Rebecca Ferguson, Cruise and Ving Rhames in Mission: Impossible Fallout

The movie carries over not only McQuarrie but key cast including Rhames, Simon Pegg (a regular since III) and Sean Harris, the Rogue Nation mastermind who commands a criminal shadow organisation called the Syndicate, and this contributes to a feeling of more-than-usual continuity between the movies. While the Mission: Impossibles always succeed swimmingly on the level of spectacle, they have less consistently been convincing on the more intimate scale – having seen all the films more than once, I still manage in the years between sequels to forget the few details that constitute what we know of Hunt’s private life.

Fallout’s climax brings together Hunt and his two most recent love interests: Rebecca Ferguson, who appeared in Rogue Nation as Ethan’s UK opposite number from MI6, and Michelle Monaghan, reprising her role as the wife Hunt married in III and then separated from to ensure her safety before the events of Ghost Protocol began. There’s a real twinge of pathos in their tender and understated reunion, a meeting between Hunt and this old flame that occurs as he’s engaged as usual with his real one and only: the job to which he is as pathologically attached as Cruise is attached to sustaining himself as his peculiar and somewhat outmoded idea of a movie star, the hardest-working man in show business, seemingly on his way to peacefully expiring while trussed up in wirework in a distant dozenth Mission: Impossible.

Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation (2015)

If Hunt is in many respects the perfect Tom Cruise role, it is due to the sense of monomaniacal absorption in the job that is built into these films, in which – excepting Woo’s endearing but slightly off-brand second movie – spy games are an around-the-clock occupation that leaves little time for cocktails and bounding between boudoirs. This suits an actor who can and will do most everything for a scene – including hold his breath for six minutes underwater – but for the life of him cannot project a naturally laid-back air, much as the relentless pitch of the movies seems to be in synch with our uptight, always-on-the-clock age. (In capturing something uniquely contemporary, these frantic films are only outdone as a franchise by the Resident Evil series and its vision of a corporate-sponsored apocalypse.)

“Running in movies since 1981”, reads the bio, possibly intern-penned, for Cruise’s otherwise quite humourless Twitter account – but this gets at something essential about the actor’s scrambling screen presence, which combines Apollonian grace under pressure with hell-bent-for-leather sprinter speed.

Kicking off with a time-sensitive warning (“This message will self-destruct in five seconds”), the hectoring, insistent staccato of Schifrin’s theme, and the spark of a lit fuse, the Mission: Impossible films propose themselves as ticking time-bombs – by the time the briefing has taken place it’s probably already too late, and every nanosecond lost makes the possibility of an 11th-hour rescue even more remote.

Mission: Impossible – Fallout (2018)

In Fallout, that fuse is racing towards a grand finale in which, alongside the playing out of unresolved interpersonal drama, the full talents of the entire IMF team are engaged, with stolen nukes to be defused, a noose-wielding lunatic to be neutralised, and a helicopter chase ending in a fraught face-off on an inaccessible cliff ledge, overseen through parallel editing that mercilessly ratchets up the tension as the final countdown runs out for humanity – far from the first potentially extinction-level event that Hunt and company have had to put the kibosh on, to the point where you wonder how much closer to oblivion they can cut it in the next go-around.

While the franchise has passed through many hands over the years, you never forget your first, and in these hair’s breadth escapes the movies still bear the imprint of the perverse pasticheur De Palma, who’d made a speciality of stretching time to the agonising breaking point in the Hitchcockian rush-to-the-rescue sequences of Blow Out, Body Double (1984) and Raising Cain (1992).

But where De Palma’s heroes often fail to arrive in time, Cruise and co haven’t let the side down yet – making Mission: Impossible the safest bet among surviving film franchises, a celebration of streamlined speed, engineering ingenuity and the thrill of the Hunt. Unbounded by borders or language, infinitely mutable behind his masks, able supply to transform setbacks into innovations, at home everywhere and nowhere, fleet of foot above all else, Cruise has given us the first great post-Cold War superspy – and as such it is only fitting that he should embody an aesthetic as restless and as mobile as circulating capital itself.

-

Sight & Sound: the September 2018 issue

Spike Lee: the BlacKkKlansman interview; the indomitable Joan Crawford; Pawel Pawlikowski’s Cold War; Mark Cousin’s on the drawings and...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.